Confronting Racism in Basketball and the Jesuits: The Extraordinary Life of Georgetown’s John Thompson

“My mother always told me to speak my mind. My father always said, ‘Son, study the white man,’” writes John Thompson Jr. in the opening chapter of his autobiography, I Came as a Shadow.

Anyone familiar with the career of the Hall of Fame basketball coach from Georgetown University knows how seriously he took both parents’ advice. To the already initiated, Thompson’s provocative and outspoken advocacy on issues of race will not be surprising. For much of his career, he was considered a “troublemaker” among elite college basketball coaches. He was a blunt, opinionated and imposing six-foot-ten-inch Black man whose success warranted inclusion in an otherwise all-white coaching fraternity. And he consistently used his position to challenge the status quo on matters of race and justice.

I Came as a Shadow, published several months after Thompson’s death in late August 2020 at age 78, reflects its author’s personality: challenging, unapologetic and unsparingly acute in its observations beyond the basketball court. According to his coauthor, Jesse Washington of ESPN’s “The Undefeated,” Thompson deliberated over every word because “he knew this would be his final testimony and how much it is still needed.” He also reminded Washington periodically that “I don’t want this to be a book about basketball.”

That sentiment could easily serve as an epigraph to the coach’s career. The game was never the objective for Thompson; it was just the instrument. “Basketball became a way of kicking down a door that had been closed to Black people,” he writes. “It was a way for me to express that we don’t have to act apologetic for obtaining what God intended us to have, and that we should be recognized more for our minds than our bodies.”

With the conversations on race in the wake of George Floyd’s death, it is difficult not to think that the same issues that branded Thompson as problematic 40 years ago now reveal him to be prescient. We are only now catching up to him. “We have entered a new era of vocalizing our humanity,” he says about the Floyd protests. “Yes, Black people are being needlessly killed by police, but there are many ways of killing a person. You can kill people by depriving them of opportunity and hope. You can kill people by saying that society is equal, then starting a hundred-yard race with most white people at the fifty-yard line.”

John Thompson Jr.: “Yes, Black people are being needlessly killed by police, but there are many ways of killing a person. You can kill people by depriving them of opportunity and hope.”

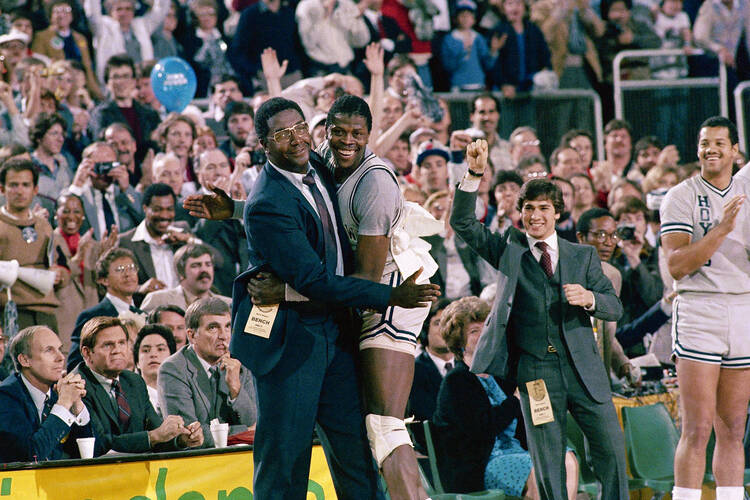

There are not any lengthy musings on Allen Iverson’s ball-handling abilities or Patrick Ewing’s dominance under the basket, but Thompson does recount the numerous relationships, events and controversies he was involved with throughout his career. He reflects on being the first Black coach to win an N.C.A.A. championship, as well as his high-profile protests against Proposition 42 that led the N.C.A.A. to rescind that discriminatory rule. He speaks with enormous gratitude about mentors both famous—coaches Red Auerbach (Boston Celtics) and Dean Smith (University of North Carolina)—and unknown, like Sametta Wallace Jackson, a grade school teacher who protected him emotionally while nurturing him academically. Thompson even goes into great detail about confronting a powerful drug kingpin in Washington. D.C. The man eventually respected Thompson’s wishes that he stay away from his players.

The book’s greatest revelations are in the glimpses Thompson allows into the history and experiences behind the man we thought we knew from his public pronouncements. After 40 years in the spotlight, it is astonishing how little insight we had into the contrasts and conflicts that animated Thompson: the indifferent, slow-to-read student who went on to make the graduation of his players the centerpiece of his program; the intimidating coach who was a self-described mama’s boy; the practicing Catholic deeply devoted to Mary; the young man whose first experience of racism was in a segregated Jesuit church in rural Maryland; a man who focused his whole life on lofty issues of equality and justice but who was an unabashed capitalist who “wanted to be rich”; a Black coach intent on correcting historical wrongs who worked for an institution that only recently began addressing its slaveholding past.

My own interest on first picking up the book was to learn about the program and the coach I had been adjacent to for four years but had never really understood. At the peak of the team’s performance in the 1980s, I had the privilege of being courtside for nearly every home game, conference tournament and N.C.A.A. playoff game, playing drums in Georgetown’s band. These were the years of “Hoya Paranoia” in which Thompson micromanaged every aspect of his team. Other than the cafeteria and classes—which his players attended religiously, without fail—the basketball program was distinctly separate from student life on campus.

Thompson’s program was so successful that at one time the Hoyas played in the national championship game in three out of four years. The all-Black teams he assembled in those years had a 97-percent graduation rate and became such a source of racial pride around the United States that Georgetown Starter jackets became iconic urban fashion statements. To Thompson’s delight, his program’s success even led some African-Americans to believe, mistakenly, that overwhelmingly white Georgetown was a historically Black college.

For the son of an illiterate tile worker and a mother who cleaned houses, it was an extraordinary rise. Thompson grew up in such a segregated world in our nation’s capital that he had no significant interactions with white people until he was recruited to play basketball at an all-white Catholic high school. When he was growing up, the affluent and white Georgetown University was just across Rock Creek Park, a few miles from where he lived, but it might as well have been on the moon.

His journey took a poignant turn in 2016, when Georgetown finally began confronting its own history with racism. In 1838, the Jesuits sold 272 slaves from their Maryland plantations to keep the struggling college afloat. Thompson had been aware that the school owned slaves, but the magnitude of the sale was deeply unsettling for him. The people who were sold were from St. Mary’s County, where his father grew up and where “the Jesuits owned everything.” The news brought back childhood memories of his first experiences of racism and segregation in the Catholic Church in that same region. “The same Jesuits who founded Georgetown owned my father’s ancestors,” he writes. “I can’t prove it, but there is no doubt in my mind.”

His adult work life had been consumed with achieving success and status and building up a university that had once owned his forebears. Is it any wonder that Thompson was a complex man who never felt he had the “luxury of just being a coach”?

I Came as a Shadow is neither a basketball book nor a sports memoir. It isn’t filled with inspirational quotes or “secrets to success” that one can practice to emulate the author. Thompson’s autobiography is the rare example of an American success story that does not revel in its own glory. Rather, it is haunted by the responsibility that his story of success carries with it.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “This is not a book about basketball,” in the Spring Literary Review 2021, issue.