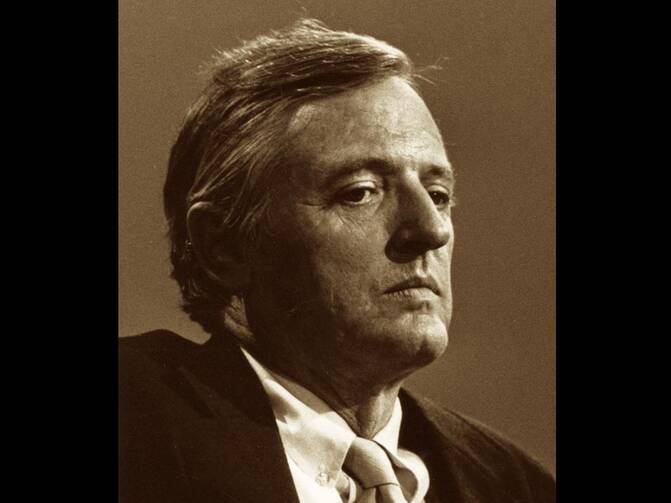

God and man in America: William F. Buckley Jr.

An issue of National Review that went online in December 2024—marking the 100th birthday of its founder, William F. Buckley Jr.—celebrated his “greatest achievement”: the “absolute exclusion of anything antisemitic or kooky” from the conservative movement. Weeks later, Jacob Chansley, better known as the “QAnon Shaman,” was among 1,500 Jan. 6 defendants pardoned by President Donald Trump, whose staunch defense of Israel stands in marked contrast to the attitudes of the “Great Replacement” Holocaust deniers whose support the president actively cultivates.

So, for now, let’s characterize Buckley’s “achievement” as a work in progress.

Which doesn’t change the fact that—17 years after his death—it is impossible to understand American politics and culture without grasping Buckley’s immense influence, as Sam Tanenhaus makes clear in Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America, a mammoth, long-awaited biography.

Timely and readable, incomplete and overly sympathetic, Tanenhaus’s book is sure to evoke comments about history repeating itself. Buckley, too, ranted about the media and universities, race and policing, elites and populists.

But of all the lessons we might take from these echoes of the past in the present, the most urgent may be this: Buckley’s ideological adversaries often made his job a lot easier. This is something Trump’s many frustrated critics should consider between now and 2028.

“In [Buckley’s] time, as in our own, no one could really say what American conservatism was or ought to be,” writes Tanenhaus, the former New York Times Book Review editor, whose previous works include Whittaker Chambers: A Life. “But for more than half a century, millions of Americans could confidently say who has been the country’s greatest conservative.”

Everything Buckley did professionally—defending the red-baiter Joe McCarthy, creating National Review, writing a national newspaper column, power-brokering in the Republican Party, running for New York City mayor, hosting the TV show “Firing Line”—was meant to enhance the power and influence of American conservatism. Tanenhaus tracks Buckley’s rise and evolution from pre-World War II isolationism and Cold War anti-communism to the anarchic 1960s and the rise of Ronald Reagan. Along the way there are tantalizing details at the intersection of the personal and political: family tragedies, bitter political squabbles, financial woes, even bizarre speculation about Buckley’s “gay”-seeming persona, fueled by a notorious public fight with Gore Vidal.

Tanenhaus is sharply critical, at times, though not quite enough to pose this question explicitly: Did American conservatism thrive because of Buckley? Or in spite of his many shortcomings?

William Francis Buckley Jr. was born on Nov. 24, 1925, the sixth of 10 children. His father seems a character plucked from a Mark Twain frontier story: a Texas “lawyer, real estate investor, and oil speculator,” who went bankrupt at 40, only to reinvent himself as a Roaring Twenties Manhattan businessman.

A devout Catholic, Buckley père saw himself as a charitable Christian, even during the Great Depression. “But the Gospel of Wealth was one thing,” Tanenhaus writes. “Government intervention was quite another.”

Thus two powerful pillars of Buckley Jr.’s life were erected: Catholicism and capitalism.

The 1930s—Buckley’s formative years—were eventful ones for American Catholics. Yet Tanenhaus never mentions the Rev. Charles Coughlin or the “New Deal priest” John Ryan. Or Dorothy Day, or Pius XII, or even Al Smith, the Catholic presidential candidate who soured mightily on F.D.R. and the New Deal.

We are told simply that the Buckleys preferred a “Catholic atmosphere [that] was fervent but also rarefied,” and wanted “no hint…of Ireland or the ‘immigrant church.’” A friend describes Buckley as “a Catholic aristocrat of the Spanish persuasion.” Yet not even the Spanish Civil War is mentioned in a book more than 1,000 pages long.

Buckley became one of the nation’s most prominent Catholics—a pivotal figure in a political party that, for complex reasons, had been hostile to Northeastern Catholics since the days of Lincoln. How this came about deserves at least as much attention as, say, the 1960s Cold War crisis in the Congolese state of Katanga.

Buckley’s first book, God and Man at Yale (1951), did pose important questions about education, as well as the awkward dance between orthodoxy and heterodoxy in both politics and faith. But how exactly did Buckley position himself as a defender of “tradition” at a 1940s Ivy League university when, as Tanenhaus himself notes, Yale was still adhering to strict quotas for Catholic and Jewish students?

To be fair, Buckley himself evaded such questions, even in his slapdash “autobiography of faith,” Nearer My God (1997), which consists mainly of friends’ musings and platitudes like “the [Catholic] church is unique [because] it is governed by a vision that has not changed in two thousand years.” In the end, though, it is important—in U.S. history in general—to be careful about who does and does not represent a dominant, established order. Buckley’s beliefs may have been (as the historian George H. Nash has put it) “traditionalist,” but they were also a “fundamental challenge to official secular-liberal America.”

By 1955 Buckley had not only created National Review; he had also found his great calling: chronicling the “unacknowledged biases of liberals” and other proud freethinkers who never noticed that “all the freethinking seemed to go in the same direction,” Tanenhaus writes. Another of Buckley’s callings, unfortunately, was exposing flaws in others that he deftly ignored in himself. He liked to repeat a line about anti-Catholicism being the antisemitism of intellectuals, yet he said little about the antisemitism of wealthy Connecticut Catholics named Buckley. And fellow conservatives worried about Jewish “divided loyalty” (between the United States and Israel), even when the same charge was hurled repeatedly at U.S. Catholics, with their pope far off in Rome.

National Review preached the gospel of free-market capitalism, even as the magazine lost millions and was kept afloat only by “family money” and years of volunteer labor from friends and siblings. To be sure, Buckley admirably evolved on a number of issues and nimbly detached himself from the ugly likes of the John Birch Society. Still, this proud Cold Warrior often recklessly “equated Communist ideas with liberal ones,” Tanenhaus notes, and railed against an expansive, expensive federal government even as he supported lavish defense budgets and international military actions.

Buckley later called Nixon’s China policy “collusion with a totalitarian regime” linked to “aggression [and] torture.” The same could have been said about state and local governments south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Yet even after Jim Crow was finally challenged, Buckley’s response was meager, to say the least.

There were, of course, legitimate questions to be asked in the 1950s and 1960s about federal and judicial power, and just how much historical damage each could actually repair. Barry Goldwater and others on the right at least attempted to make such a case. But that was not what National Review was suggesting in 1958 when, on the question of civil rights, it offered this “sobering” insight: that whites were “the advanced race.” The editorial “Why the South Must Prevail,” Tanenhaus writes, “haunts [Buckley’s] legacy and the conservative movement he led.”

It does nothing of the kind, of course, at least not among the MAGA crowds at the barricades of 21st-century conservatism.

Which provokes a crucial question: With so many shortcomings, how can we explain Buckley’s profound influence?

He was undeniably entertaining and funny. Buckley also had a tremendous work ethic, and made a point of venturing far beyond the Manhattan and Beltway bubbles. He was also open-minded—about emerging technologies like TV, as well as third-party movements, helping his brother Jim become a U.S. senator not as a Republican but as a member of New York State’s Conservative Party.

But Buckley was also blessed to live in chaotic times. The post-World War II left was rife with its own contradictions, hypocrisies and wildly unrealistic expectations for what the federal government could—effectively—accomplish. Radical groups like the Birchers were a menace, but they were also a clear and present warning, as was Barry Goldwater’s easily dismissed 1964 presidential campaign.

Buckley presciently sensed that new coalitions were forming, especially during his fascinating 1965 run for New York City mayor. It clearly wasn’t just paranoid farmers in the square states who believed something was profoundly wrong in the United States. It was also nurses, cops and other “hardhat” types in the Ellis Island enclaves of big Northeastern and Midwestern cities.

It bothered Buckley when conservatives could not “say what they are for—only what they are against.” But following one of the most stunning and surreal presidential terms in American history (L.B.J. from 1965 to 1969), there was so very much for Buckley—and Goldwater, and Nixon and California governor Ronald Reagan—to simply oppose, to “stand athwart history, yelling ‘stop’,” as Buckley put it in National Review’s first issue, in 1955.

Reagan’s 1980 election likely represented the high point of Buckley’s influence. It was decades in the making, and rife with tension and conflict, but overall the message and messenger were largely in sync. Which is also what makes 21st-century debates about Buckley and a very different kind of messenger—Donald Trump—so provocative.

Yes, Buckley voiced grave concerns about Trump back in 2000. The same can be said, at this point, about a big chunk of Trump’s cabinet and inner circle. The main reason Trump is no Reagan is because the current president’s operational style is much closer to that of another 1960s governor and White House aspirant: George Wallace, who, for all of his vile race-baiting, also won millions of blue-collar votes far away from the Jim Crow Confederacy. Which means that the hardest question facing Democrats and progressives right now is this: After decades of merely flirting with fiery, toxic populists, why have so many American voters committed—for over a decade now—to the most divisive and destructive of them all?

Perhaps Buckley himself couldn’t answer that question. But would he at least stand up and yell “stop”?

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “God and Man in America,” in the July/August 2025, issue.