Review: An accurate look at Muslim beliefs

During a papal press conference in 2014, Pope Francis called on Muslims to condemn acts of terrorism committed by their co-religionists. “There needs to be international condemnation from Muslims across the world. It must be said, ‘No, this is not what the Quran is about!’”

American political commentators and other Christian leaders voice this sentiment, too. In 2015, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the archbishop of New York, wrote in the New York Post, “We encourage the majority of Islam to speak up and condemn these attacks...and say, ‘This is not Islam.’”

This persistent refrain asking Muslims to condemn terrorism is almost always well intentioned; many of those voicing it have actively sought to combat untrue and unfair perceptions of Muslims. But as Todd Green, a religious studies professor at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, writes in his new book,Presumed Guilty: Why We Shouldn’t Ask Muslims to Condemn Terrorism (Fortress Press. 250p $16.99), it is a question we must let go of.

When Christian leaders and other prominent voices call on Muslims to condemn terrorism and fail to highlight myriad existing statements condemning it, it gives the false impression that Muslims are not already speaking out.

Muslims, Green notes, are already condemning such violence, and they often invoke the Islamic tradition to demonstrate why these acts are wrong. Evidence of these condemnations is just a Google search away; search for “Muslim condemnations of terrorism” and you will find countless entries, including statements signed by Muslim religious leaders of various denominations, news reports of massive demonstrations and social media campaigns launched by ordinary believers in the name of peace. When Christian leaders and other prominent voices call on Muslims to condemn terrorism and fail to highlight these myriad existing statements, it gives the false impression that Muslims are not already speaking out. This, in turn, reaffirms the common misconception that Islam promotes violence.

But the idea that Islam promotes violence ignores the complex causes of violence, and it misunderstands the role of religion in people’s lives. Green, who formerly advised the State Department on Islamophobia, walks readers through much of the scholarship on terrorists’ motivations, which demonstrates that social and political factors explain more than religious convictions do. The vast majority of the 1.7 billion Muslims around the world live out their Islamic faith in ordinary acts of charity and self-sacrifice.

Like Christians, Muslims have diverse ways of approaching their religious tradition and interpreting their texts. Just as we do not give Christianity’s worst adherents the right to define the religion, Green writes, we should not allow Muslims who commit acts of violence to speak for Islam. Green’s final thesis is that when people in the West call on Muslims to condemn terrorism, they are often, perhaps unconsciously, deflecting attention away from their failures. It sets up an us-versus-them scenario, in which we see them only as the source of the world’s violence and terrorism, rather than examining the complex set of factors—including our own histories of violence—that play a role. This lets us maintain the best vision of ourselves and compare it to the worst version of the “other.”

Just as we do not give Christianity’s worst adherents the right to define the religion, we should not allow Muslims who commit acts of violence to speak for Islam.

Green describes plenty of oft-forgotten, unsavory episodes from Christianity’s past to drive home this point. Readers will find more examples in Rita George-Tvrtkovic’s book, Christians, Muslims, and Mary: A History (Paulist Press. 272p $27.95), which traces how Mary has figured into Muslim-Christian relations. George-Tvrtkovic, a Catholic historical theologian at Benedictine University in Lisle, Ill., chronicles the ways that Mary has been used as both “bridge” and “barrier” between Christians and Muslims. Mary has brought both communities together, and she has been used to drive them apart—sometimes literally. For example, an image of Mary was sometimes emblazoned on Christian military banners in battles against Muslim armies.

Though most Catholics today think of Mary as nothing other than the benevolent and loving mother of God, she has been invoked throughout history as a warrior against perceived enemies of the church, including Muslims. The most striking example of this in George-Tvrtkovic’s book is a 17th-century depiction of Mary and the infant Jesus standing on top of the corpse of a defeated Turk. Mary has a sword and rosary in hand, and Jesus holds the Turk’s head, which his mother has severed.

This depiction is illustrative of a broad trend that George-Tvrtkovic describes: Catholics’ long-standing association of the rosary with wars against Muslims. During and after the battle of Lepanto against the encroaching Ottoman navy in 1571, the Catholic armies saw Mary as the key to their success, and they continued to invoke her—and the newly popular rosary devotion—against Muslims (and Protestants). The feast of Our Lady of the Rosary—originally Our Lady of Victory—celebrated on Oct. 7, marks the Lepanto battle. As George-Tvrtkovic notes, the event looms large in the minds of a small subset of Catholics today who invoke the blessed mother to justify their hostility toward Muslims.

But the history of Mary in Muslim-Christian relations has bright spots as well. George-Tvrtkovic describes how Christians and Muslims have invoked Mary as a unifying figure, and her persona has drawn both communities together in pilgrimage. From Turkey to Jordan to Pakistan, Christian and Muslim pilgrims visit holy sites dedicated to Mary to remember her and seek her intercession.

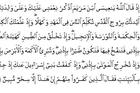

The book also offers in-depth discussions of Mary’s role in the Islamic tradition. Readers may be surprised to learn, for example, that the story of the annunciation in Luke’s Gospel closely resembles a similar story about Mary in the Quran. This window into the “Islamic Mary”—Maryam in Arabic—will be particularly illuminating for Catholic audiences. According to a survey by the Bridge Initiative (which I helped commission), a vast majority of U.S. Catholics (88 percent) are unaware that Muslims honor Mary as Jesus’ virgin mother, despite the fact that Muslims’ reverence for her is praised in the “Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions” of the Second Vatican Council.

George-Tvrtkovic writes that Mary can be an example for us. Her qualities, attested to by both traditions and evident in the annunciation story, serve as a model for what a truly dialogical relationship between Christians and Muslims can look like. But George-Tvrtkovic also reminds readers that, like our ancestors, we have agency over our symbols. Ultimately, it is up to us to decide who Mary is—a bridge or a barrier.

Mary can be an example for us. Her qualities, attested to by both traditions and evident in the annunciation story, serve as a model for what a truly dialogical relationship between Christians and Muslims can look like.

As different as these two books are, Presumed Guilty and Christians, Muslims, and Mary give us a clearer and fairer picture of the oft-demonized Muslim “other,” and they call into question the sometimes rose-colored view Christians have of themselves. Green writes that his book should be seen as “an invitation to raise our standards and examine our prejudices.” The same could be said of George-Tvrtkovic’s.

Many of the crucial, revelatory takeaways from both books come toward the end, only after readers have made their way through extensive details. Readers will profit from a peek at the introductions and conclusions early on. Both Green and George-Tvrtkovic write in a compelling and accessible style, successfully walking readers through subject matter that requires deep nuance. Both books would fit well into high school and undergraduate courses, and journalists and lay readers of diverse backgrounds will benefit much from them.

Both Green and George-Tvrtkovic have written timely texts that help elevate our thinking and improve the ways we relate to our Muslim brothers and sisters. Readers who share these goals will be well served by both books.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Fair Picture of Muslim Belief,” in the Fall Literary Review 2018, issue.