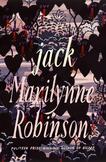

Review: Marilynne Robinson returns to Gilead

There are risks in writing a doctoral dissertation on a living writer. The first is trying to assess an evolving canon; another is getting bored with the writer’s latest work.

Marilynne Robinson’s fourth installment of the Gilead series, Jack, is a meditative continuation of the parable of Jack Boughton, wayward son and godson of two pastors in small-town Iowa. The plot of Jack fleshes out what is adverted to (but never developed) in the other novels, which cover overlapping but not identical ground.

The novel begins in Bellefontaine, an antebellum cemetery north of St. Louis. We amble slowly with Jack and his would-be wife, Della, under cover of darkness. This start was not easy reading, and this devoté feared Ms. Robinson had lost her touch. At one point Jack muses, “A night can seem endless.” (So can a novel, I grumbled.)

Soon, however, it became clear that Robinson was deliberately slowing down our pace. At daybreak, the pair emerges from the cemetery like Adam and Eve, sloughing off the anonymizing bliss that night afforded. They must now face the dulling shame reserved for couples in interracial romances in 1950s America, a motif that has played quietly in the background of the Gilead series until now. We meet the solicitous ministers and family members who want the best for Della and Jack, up to but excluding their free consent for the couple to be married.

Robinson showers us with allusions to consider: Hamlet and the Prodigal Son, Paradise Lost and the Garden of Eden, Crime and Punishment and the Prince of Darkness.

Robinson showers us with allusions to consider: Hamlet and the Prodigal Son, Paradise Lost and the Garden of Eden, Crime and Punishment and the Prince of Darkness. As Jack walks past thriving Black churches and St. Louis neighborhoods later destroyed by eminent domain laws, Robinson’s point is subtle but clear.

Jack’s accumulated missteps and bad habits are periodically countered by renewed hope in his love for Della. One morning Jack cleans himself up and “walked out into a world oddly untransformed. Miracles leave no trace.... [T]hey happened once as a sort of commentary on the blandness and inadequacy of the reality they break in on, and then vanish, leaving a world behind that refutes the very idea that such a thing could have happened.”

Those familiar with the Gilead story will find here another beautiful meditation on grace operative in spite of habits of despair and the social sins that feed them. Like its author, Jack is many things, but boring is not one of them.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Return to Gilead,” in the December 2020, issue.