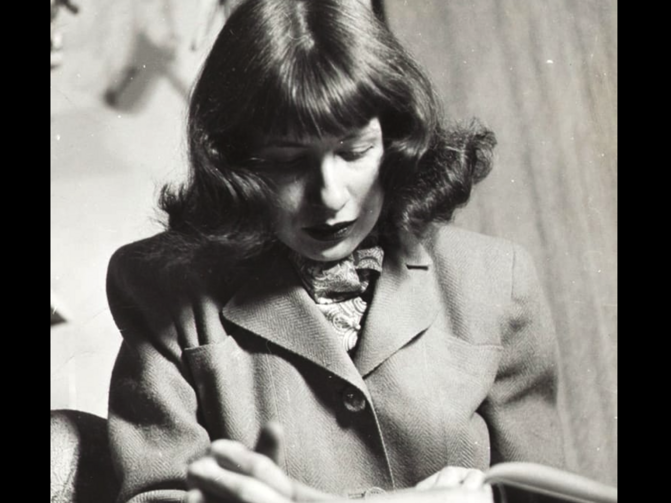

Review: Amy Clampitt, the ‘late bloomer’ of poetry

Amy Clampitt, widely eulogized as a “late bloomer,” was 63 years old before she was recognized as a world-class poet. Rising to meteoric heights in the poetry world is by itself daunting, but when one considers her age and that most poets burn bright in their 20s and then steadily lose their fire, one is even more impressed. Willard Spiegelman’s probing biography, Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt, describes how she did it.

Examining Clampitt’s career, the influences behind her poetry and Amy herself—he calls her Amy—Spiegelman suggests Clampitt succeeded mostly because her work had a vitality and a spiritual component that other poets lacked. Her poetry teems with metaphors and buzzes with sound. It is nothing like the terse, imagistic poems that were popular in the latter part of the 20th century.

Much of the credit for Clampitt’s achievement belongs to the complex, exuberant poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, S.J., which inspired Clampitt’s luminous style. As Spiegelman describes it, she was first taken by the work of Hopkins at Grinnell College. His ornate imagery, sprung rhythms and sense of the spiritual undergirding the physical had a major impact on her.

As Clampitt said in a Paris Review interview, her greatest debt was to Hopkins. She owed him her “delight in all things physical, the wallowing in sheer sound, [and] the extravagance of the possibilities of language.” In fact, Hopkins’s poem “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” served as the basis for “The Kingfisher,” the title poem of Clampitt’s first collection.

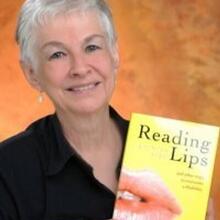

A professor of English at Southern Methodist University and a former editor of Southwest Review, Spiegelman previously edited Love, Amy: The Selected Letters of Amy Clampitt, whose positive reception led him to write this biography. He had met Clampitt on several occasions and published her work over the years, although he was initially taken aback by Clampitt’s poems because of their style.

Referencing Clampitt’s letters, essays, journals, poems, novels, one play and interviews, Nothing Stays Put includes reminiscences of family, friends, colleagues and professional associates. That last category includes well-known figures like Howard Moss, Clampitt’s editor at The New Yorker, the renowned literary critics Harold Bloom and Helen Vendler, and a longtime friend, the poet Mary Jo Salter, a retired professor at the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars.

Spiegelman focuses on Clampitt’s rise to literary fame and her years as a celebrity, but also covers Clampitt’s early life. He begins with her great-grandfather, who came to Iowa as an orphan and started farming, a vocation he passed on to his son and grandson. Both younger men graduated from college and had a penchant for reading and writing that Amy inherited—as she did their appreciation for nature. One of her first memories, Spiegelman notes, is of a patch of violets growing in the field.

The oldest of five siblings, Clampitt was raised in a family that valued simplicity in speech, dress and demeanor, and that attended Quaker religious services. She was a bookish child and enjoyed spending time in her grandfather’s library. She daydreamed about becoming a painter, although she had felt a connection to poetry from an early age.

After she graduated from college, Clampitt moved to New York to attend Columbia University but dropped out after several months. Living in Manhattan, she worked as a secretary at Oxford University Press, then later as a librarian for the Audubon Society and finally as an editor for E. P. Dutton. During these years, she also traveled to England and Europe.

Back home in the United States, she had several love interests before she found her longtime partner, Harold Korn, whom she married a few months before she died. She also made frequent visits to the Cloisters, a part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City specializing in medieval European art and architecture, where she had an almost mystical experience that reignited her love of poetry with its connection to the divine.

Visiting the Cloisters during Holy Week, she was astonished by the medieval tapestries, especially in their rendering of flowers. As the regular Sunday program commenced with the Kyrie, the Greek prayer for mercy, the plaintive sound of its cry for help seemed to merge with the sunlight coming through a 13th-century window. She felt a profound sense of connection.

She referred to this awareness as a baptism not of water but of light. Many of her poems use the concept of a world flooded with light, referencing both the brilliance of sunlight and the religious connotation of the light of the world and the life-giving force of Jesus Christ.

After Clampitt became an Episcopalian, she joined St. Luke in the Fields, a High Anglican parish known for its “architectural beauty, gorgeous music, and political activism”—and for its pastor, the Rev. James H. Flye.

Flye, who had been a mentor to James Agee, impressed Clampitt. She dedicated her poem (which provided the title of this biography) “Nothing Stays Put” to his memory.

Clampitt also once considered entering the convent. During this time, she wrote and revised three novels. All were rejected as being short on conflict and unwieldy with adjectives. She also followed the monastic practice of lectiodivina, meditating on Scripture “as a way to understand Christ.”

After Norman Morrison, a Quaker, immolated himself in an anti-war protest in 1965, she felt the deep call of her Quaker roots and joined the anti-Vietnam War movement, purposely carrying a banner that identified her as a poet. Gradually, she broke away from her church because she thought they did not take a strong stand against war.

Though she thought of herself as a novelist early on, Clampitt tended to put her most profound moments into poetry. This includes the Cloisters incident described above, which she referred to in “The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews.” Published in The New Yorker in 1978, the poem launched her career and exemplifies her extravagant style. Even her final book, The Silence Opens, alludes to the Cloisters tapestry.

She was captivated by the poetry inherent in the moment. As she explained, “the sentences broke in a way that was not my usual style….” Then they began “to reach out for rhymes…. I didn’t have to look for them. They simply came.”

Clampitt eventually earned a place among the nation’s literary lions, and her poems appeared in prominent publications like The Atlantic, The Paris Review and The New Yorker. She received major awards for her work, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a MacArthur Fellowship and several honorary doctorates, and was named writer-in-residence at prestigious colleges.

Nothing Stays Put ends with Clampitt’s death at 74 from ovarian cancer. In a bow to her love for nature, the poet William Logan sent rose petals “for the late bloomer” to be scattered over her remains.

Clampitt chose to have her ashes buried beside the birch tree growing in the backyard of her home. This was the tree she watched from the window beside her desk where she created the difficult, vibrant poems that fuel this cogent biography and give meaning to her life and legacy.