Review: The U.S. is a nation of immigrants. Or is it?

Pope Francis and President Barack Obama were among the dignitaries who gathered at Washington’s Cathedral of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in September 2015 for the canonization of the Spanish-born Franciscan priest Junípero Serra, best known for his 18th-century missionary work in what would become California. “Father Serra’s sainthood has been controversial,” The New York Times noted, because “he is seen by many Native Americans as a colonialist who helped establish a system of Spanish subjugation and helped carry disease into their communities.”

On the other hand, The Times added, “many Latino Catholics celebrated Father Serra’s canonization as a mark of legitimacy for all Hispanics.”

The intersections of history and ethnicity, and race and power, have since become only more fraught and more complicated, an evolution illustrated (sometimes unintentionally) in Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s provocative Not “A Nation of Immigrants”: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion.

Dunbar-Ortiz calls for all descendants of immigrants to acknowledge the far-reaching consequences of what she and others call “settler colonialism.”

To Dunbar-Ortiz, whose previous books include An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (2014), the Serra canonization was an end result of “the process of rooting the US founding with 1492,” as well as of “the Roman Catholic Church in the United States [becoming] Americanized.” For centuries, immigrants fell into an “Americanization process...that suck[ed] them into complicity with white supremacy and erasure of the Indigenous peoples,” she writes. Dunbar-Ortiz calls for “all those who have gone through the immigrant or refugee experience or are descendants of immigrants to acknowledge” the far-reaching consequences of what she and others call “settler colonialism.”

Dunbar-Ortiz’s style of activist scholarship has catapulted her to a new level of prominence in recent years. Her work was one of the inspirations behind Raoul Peck’s 2021 HBO documentary series “Exterminate All the Brutes,” and it has been featured of late in media outlets ranging from The New Yorker to Teen Vogue. In 2017, the Lannan Foundation, a family nonprofit “dedicated to cultural freedom, diversity and creativity,” awarded Dunbar-Ortiz its Cultural Freedom Prize, citing her work as an “activist with the global indigenous people’s movement for national sovereignty,” as well as her work with “social movements for women’s equality, and for the rights of oppressed nations in Central America.”

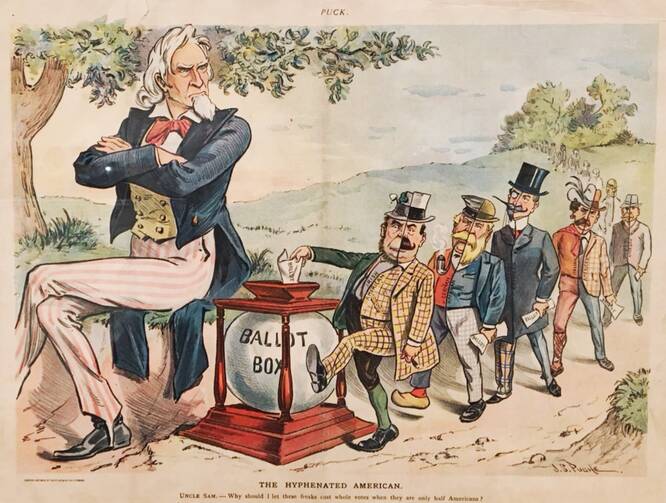

John F. Kennedy’s 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants, serves as a springboard for Dunbar-Ortiz. Generations of readers have uncritically regurgitated not just Kennedy’s phrase but also certain underlying assumptions that, Dunbar-Ortiz writes, represented a “benevolent version of U.S. nationalism,” serving to justify both American diversity and white supremacy.

John F. Kennedy’s 1958 book, A Nation of Immigrants, serves as a springboard for Dunbar-Ortiz.

Sadly, much of the historical analysis Dunbar-Ortiz offers up is difficult to dispute. Just four years before Kennedy’s celebration of immigrants, President Eisenhower launched the deplorable “Operation Wetback” to “round up and deport more than a million Mexican migrant workers.” It was merely the latest indignity along the southern U.S. border in the wake of the “military invasion and annexation of half of Mexican territory” a century earlier.

In the mid-19th century, of course, slavery had become “the economic bedrock of the United States,” and desperate, starving European immigrants had begun arriving in unprecedented numbers. Building on the Australian scholar Patrick Wolfe’s concept of “settler colonialism,” Dunbar-Ortiz argues that as destitute and despised as these immigrants may have been, they ultimately were incentivized—by naturalization laws explicitly referring to “white persons”—to reinforce the American violent style of imperialist capitalism across the continent and around the world.

The consequences, especially for people of color, have been not only awful but also enduring, as illustrated by more recent U.S. misadventures in Central America and a refugee border crisis that endures to this day.

While these parts of Dunbar-Ortiz’s book are compelling and convincing, others are more muddled.

In fact, long before the idea of the U.S. as a nation of immigrants “was hatched in the late 1950s,” as Dunbar-Ortiz puts it, the concept had its adherents—from J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur to “The Melting Plot” playwright Israel Zangwill. Similarly, references to the “American Dream” as a “meme” or a “concept invented in 1931,” are likely to send some confused readers to Dunbar-Ortiz’s footnotes—or at least to Google.

When Dunbar-Ortiz refers to the infamous New York City draft riots, meanwhile, she not only gets their month wrong but also overlooks a crucial component of this violent episode. It is true that many “Irish American Catholics engaged in riots” and that much “of their anger went into attacking and killing Black people.” But the July (not June) 1863 violence also coincided with annual celebrations of British Protestant victories over Catholics in 1690s Ireland.

Such toxic displays of upper-class Anglo chauvinism—transported from the Old World to the New—also accelerated immigrant rage, some of which was aimed at challenging the dominant culture rather than reinforcing it. Scholars intent on analyzing immigrant complicity in American racism sometimes unwittingly reinforce cherished right-wing myths about past newcomers that they were generally docile, assimilable and not disruptive at all.

Dunbar-Ortiz also ignores the biases of past (so-called) progressives and even radicals whose presence on the “right side of history” deserve a bit more scrutiny. Not “A Nation of Immigrants” notes that even after the nativist 19th-century Know-Nothing Party faded, its “ideological tendency continued in US politics, becoming dominant in the mid-twentieth century in opposition to the civil rights movement and immigration, including among white Catholics when they were no longer the target.” This century-spanning sentence elides several crucial points, including the fact that the anti-immigrant Know Nothings were by and large absorbed into the anti-slavery Republican Party. This then pushed millions of “white Catholics” into the arms of the pro-slavery Democratic party.

Dunbar-Ortiz ignores the biases of past (so-called) progressives and even radicals whose presence on the “right side of history” deserve a bit more scrutiny.

So, yes, one of the “unspoken requirements for immigrants and their descendents to become truly ‘American’ has been to participate in anti-Black racism and to aspire to ‘whiteness.’” But this process was actually exacerbated by anti-slavery Radical Republicans—the progressives of their day—who themselves refused to include immigrant Catholics in their definition of what an American was.

The consequences of this (if you will) illiberal progressivism have been substantial. One could argue that they linger to this day, including each time a U.S. senator asks a judicial nominee if he or she is now, or has ever been, a Knight of Columbus.

It is also worth noting that Dunbar-Ortiz’s disdain for “nation of immigrants” rhetoric is shared (for different reasons, of course) by conservative groups such as the neo-nativist Federation for American Immigration Reform. In 2018, the Trump-appointed director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services even removed the phrase “nation of immigrants” from the organization’s mission statement.

The move was blasted by many activists, including devotees of America’s traditional commitment to diversity. These are the kinds of people who, according to Dunbar-Ortiz, flocked to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical, “Hamilton,” for its “immigrant story with an inspirational message to counter the toxic resurgence of nativism that would soon bring Donald Trump to the presidency.” But the Broadway musical was more chic than radical to Dunbar-Ortiz, who has harsh words for Miranda, “Hamilton” and Alexander Hamilton, the immigrant founding father.

“Multiculturalism,” she writes, is little more than “the mechanism for avoiding acknowledgment of settler colonialism.”

Dunbar-Ortiz rightly notes, contrary to what many devotees of Fox News might believe—that it was actually 19th-century immigrants who pioneered and benefited from “identity politics.” The end results of those politics gave us, according to Not “A Nation of Immigrants,” “urban police forces [that were] virtually all white and mostly Irish American” as late as the mid 1960s, as well as “six of nine Supreme Court justices [who] were Catholic while two were Jewish” (as of 2019).

If nothing else, these issues certainly produce strange bedfellows. After all, one staunch critic of police departments that were “occupied by Roman Catholics” was Hiram Evans, leader of the 1920s Ku Klux Klan.

To her credit, Dunbar-Ortiz holds rightward-drifting immigrants past and present to the same standard. If America’s “settler colonial foundation is to be eradicated,” she writes, the “desire to relieve the non-European migrant or descendants of enslaved Africans from responsibility is understandable, but not sustainable.”

But this raises important questions about just how inclusive or broad-based a movement with the goal of “eradicating” America’s colonial foundation can be.

Perhaps immigrants who admire St. Junípero Serra (like, say, the immigrants who gave us Antonin Scalia or Samuel Alito) have been sucked into white supremacist complicity. Perhaps, also, they have legitimate questions about anticapitalist movements, especially those with well-documented hostilities to religion and faith-based activism.

In the end, Not “A Nation of Immigrants” is a fierce diagnosis of what continues to tear America apart. As for what can actually build us up, perhaps we can look to the Gospel of Mark—“Whoever is not against us is for us”—for a subtle but important variation on the antagonistic or inflexible discourse that prevails all across the political spectrum these days.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Different History of the United States,” in the October 2022, issue.