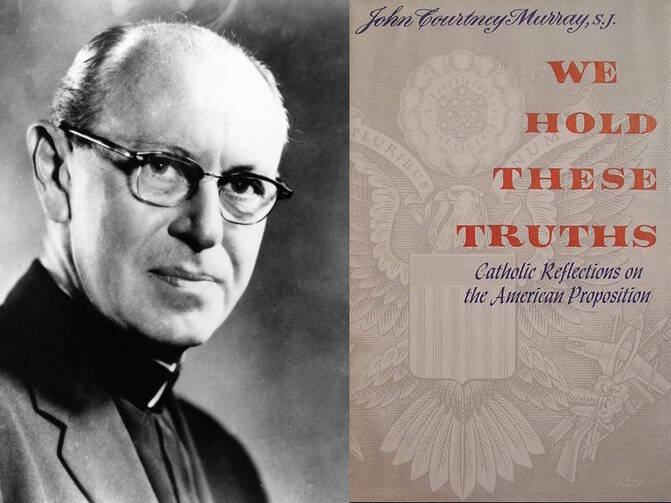

As the Fourth of July approaches, it is perhaps a good time (is it ever a bad time?) to look back on one of the great Catholic theologians of the American democratic experiment, especially in these days when its footing can seem a bit precarious: John Courtney Murray, S.J. Noted primarily for his work on religious liberty, Courtney provided much of the basis for theological and political reflection on the relationship between church and state on these shores through his voluminous writings, including his 1960 book We Hold These Truths, and his participation in the Second Vatican Council. The Jesuit theologian was also an instrumental figure in the Vatican II declaration on religious freedom, “Dignitatis Humanae.” In 1960, Murray even made the cover of Time magazine.

After being ordained to the priesthood and receiving his doctorate in theology, Murray became a professor at Woodstock College in Maryland shortly before the Second World War started; soon after, he was also named editor of the scholarly journal Theological Studies, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. Already during the war, Murray was active in efforts to create a postwar political framework for Germany and other conquered countries. During these years, he also began his work as an associate editor of America. He would remain on the masthead of the magazine for many years, though he functioned more as a correspondent, and our archives are rich with articles from him—a sampling can be found here.

By the mid-1950s, Murray’s work on religion and public life had earned him a national reputation—as well as the ire of the Vatican.

By the mid-1950s, Murray’s work on religion and public life had earned him a national reputation—as well as the ire of the Vatican for what was seen as a departure from traditional Catholic ideas of the primacy of the church in civil society. In 1954, Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, prefect of what is now the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, ordered Murray to stop writing on issues of religious liberty. The restriction on publishing would last for almost a decade.

When Murray’s fortunes reversed, it was in dramatic fashion. Invited to participate as a theological advisor in the second session of Vatican II, he was asked to help draft what eventually became “Dignitatis Humanae,” the council’s groundbreaking declaration on religious liberty and how the Catholic Church should relate to civil society—including the assertion that all people should be free from religious coercion, a radical departure from previous church teaching.

Murray died in 1967, just two years after the council ended. His reputation continued to grow in the United States after his death, in part because many Catholic theologians and political thinkers adopted his vision of U.S. Catholics serving as “guardians of the American consensus”—not strangers in a strange land, but an integral part of the American state. In this ideological framework, the church’s long embrace of natural law principles would allow Catholics to play a unique role in preserving the American political institution—itself more or less based on natural law—in the face of any new ideology or idiom.

In 2005, a parish priest from San Mateo, Calif., wrote an appreciation of Murray for America. You might recognize the author’s name these days, because Pope Francis named him a Cardinal of the Catholic Church recently: Bishop Robert W. McElroy of San Diego. In “He Held These Truths,” McElroy argued that Murray’s work

provided a prism through which the Catholic community could fully reconcile both its doctrinal heritage and its dedication to the principle that no government should seek to restrict or impose religious faith upon its citizens. His piercing and precise treatments of questions ranging from the dangers of secularism to the role of ethics in international affairs to the relationship of law and morality dazzled readers with their insight, breadth and elegance.

It was no exaggeration, McElroy wrote, “for Time magazine to designate Murray and Reinhold Niebuhr as the primary architects of a renewed role for religion in American public life at mid-century, a role that recognized the pluralism and freedom of the United States as a source of moral strength and direction.”

Not everyone was such a fan. In 2013, Professor Michael Baxter argued in America that Murray had misunderstood the nature of U.S. Catholicism, and failed to see “a schism within the American Catholic community…over the right attitude to adopt toward the established polity.” In other words, the church that Murray had seen as a leaven in the American experiment had instead become as fractured as any other political group.

Time magazine designated Murray and Reinhold Niebuhr as the primary architects of a renewed role for religion in American public life at mid-century.

“His Catholic version of American exceptionalism blinded him to the danger of Catholics’ being absorbed into U.S. political culture, overtaken by its polarizing dynamics, divided into partisan camps, dissolved into just another religious denomination to be managed by political elites, whether liberal or conservative,” Baxter wrote. “In other words, Father Murray did not foresee the danger of the U.S. Catholic community ceasing to be a united ecclesial body, ceasing to be (as we used to say) ‘the church.’”

Baxter's thesis seems particularly apt given the current political situation in the United States, where the Supreme Court's overturning of Roe v. Wade on June 24 was followed by loudly partisan celebrations or denunciations by politicians and even many religious figures, including Catholics, on both sides of the issue. Recent polls have indicated that Catholics are just as divided (and divisive?) as non-Catholics on many pressing political issues.

Writing in the aftermath of the Capitol insurrection in January 2021, Professor Massimo Faggioli agreed in part that “Murray and his work are no longer as well known or as popular among Catholics as they used to be,” and that American society—and Catholic participation in it—had taken turns Murray might not have anticipated: “The culture wars emerged from contentious issues of life in the 1970s and 1980s, but over time they have also encouraged an attack on the very idea that the church can live in a multicultural and multireligious society,” Faggioli wrote. “Calls to Catholics to unite in democracy do not always find much fertile ground now, after years of cheap skepticism about the careful distinctions required of Catholics in a constitutional democracy.”

However, Faggioli believed that Murray still had much to offer us in terms of imagining a political, religious and societal future—not because of his emphasis on the special role of Catholics in the American experiment, but because of his stress on the importance of a healthy pluralism.

“A generation of Catholics has been trained to think exclusively in terms of ‘non-negotiable values’—a notion that has been intellectually and spiritually a disaster, and on occasion a goad to extremism,” Faggioli wrote. “The Catholic Church in the United States will begin to heal itself when it accepts the need to think in terms of healthy secularity—not only in the relationship between church and state, but also in the relationship between religious ideology and the reality of a world that is and will remain plural.”

Later that year, America editor in chief Matt Malone, S.J., returned to Murray in his "Of Many Things" column, noting another insight from the great theologian that was pertinent to our society today. "For Murray, civil society is the flowering of the human person as homo politicus," Malone wrote. "We are not radically autonomous individuals, but rational social animals. We need reasoned debate, not simply because it is better than a bare-knuckle brawl, and not simply because the manners of polite society require it, but because it belongs to our human nature to reason and to argue in civility."

That is a lesson we could perhaps all profit from remembering this week.

"A generation of Catholics has been trained to think exclusively in terms of ‘non-negotiable values’—a notion that has been intellectually and spiritually a disaster."

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Sinnerman,” by Michael Waters. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

Theophilus Lewis brought the Harlem Renaissance to the pages of America

Talking truth and lies with the Norwegian novelist who won the Nobel Prize

Andre Dubus on prayer and parental love

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Joan Didion: A chronicler of modern life’s horrors and consolations

Happy reading!

James T. Keane