Review: Beauty in the corrupt world of the first century

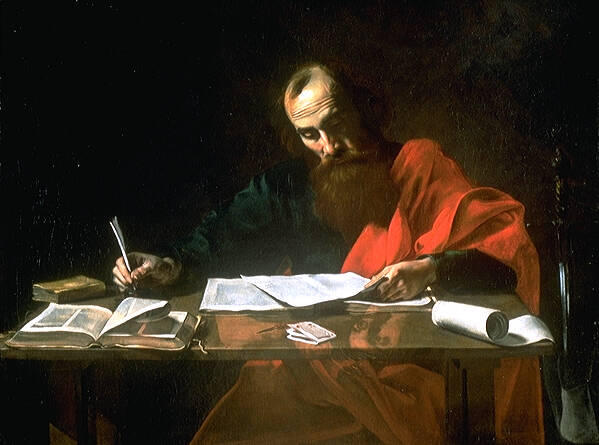

Christos Tsiolkas’s Damascus brings us into a violent, miserable, fallen world. The Australian author’s most recent novel repeatedly paints deeply disturbing scenes of bodies ruined, defiled, broken and raped in revenge, sacrifice, lust and hatred. It is visceral and vivid; it is the reality in which Paul the Apostle lived, and it is terrifying.

The world of the first century is the terrible canvas through which moments of light and beauty cut. In speculative narratives about Paul, Lydia of Thyatira, Timothy (Paul’s collaborator and co-worker) and Thomas, we are offered respite in moving visions of two intertwined concepts central to the emerging faith: love and equality in Christ. Perhaps Tsiolkas sets out to contrast these so intensely against their historical background because we moderns cannot grasp how earth-shattering they were.

Tsiolkas depicts acts of profound kindness and love toward the most marginalized individuals in the first decades after the death of Christ, but it is the love shared among the followers of Jesus, both the apostles and later generations, that is most richly developed in Damascus. They are lovers and they are loved, and our culture would be inclined to read their relationships here as almost romantic. The love represented is sometimes eros, need-love, desire for the beloved, yes. But it is eros on the road to agape—love that is self-giving.

With Damascus, Tsiolkas has recovered a message that would seem universal in time: that for all the ugliness of a corrupted world, there is still to be found within it truth, goodness and beauty.

In a moment of deep insight, Tsiolkas imagines for us what it might have been like to mark oneself as we now so perfunctorily do—to make the sign of the cross—in a world in which “the ancient humiliation,” “those abominable gallows,” the ignoble and brutal act of crucifixion, was a lived reality.

To sit together, as Lydia does in Philippi, with merchants and slaves, Jews and Gentiles, men and women—and to participate as equals in the eucharistic memorial, a simple act of table fellowship—was to tear the world apart. To propose that all might be equal in Christ, that all human life might be inviolable and sacred and worthy of love, was to present a radically subversive alternative.

Tsiolkas is neither a theologian nor a biblical scholar, nor does he present himself as one, but he has read widely and seriously. He has described his fiction as “heretical, but not blasphemous.” He is a novelist, and first and foremost he is himself: a man who knows what it is to struggle in and against the world. With Damascus, Tsiolkas has recovered for himself and his readers a message that would seem universal in time if we were not acquainted with its origins and emergence, its breaking into history: that for all the ugliness of a corrupted world, there is still to be found within it truth, goodness and beauty.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Beauty in a corrupt world,” in the April 27, 2020, issue.