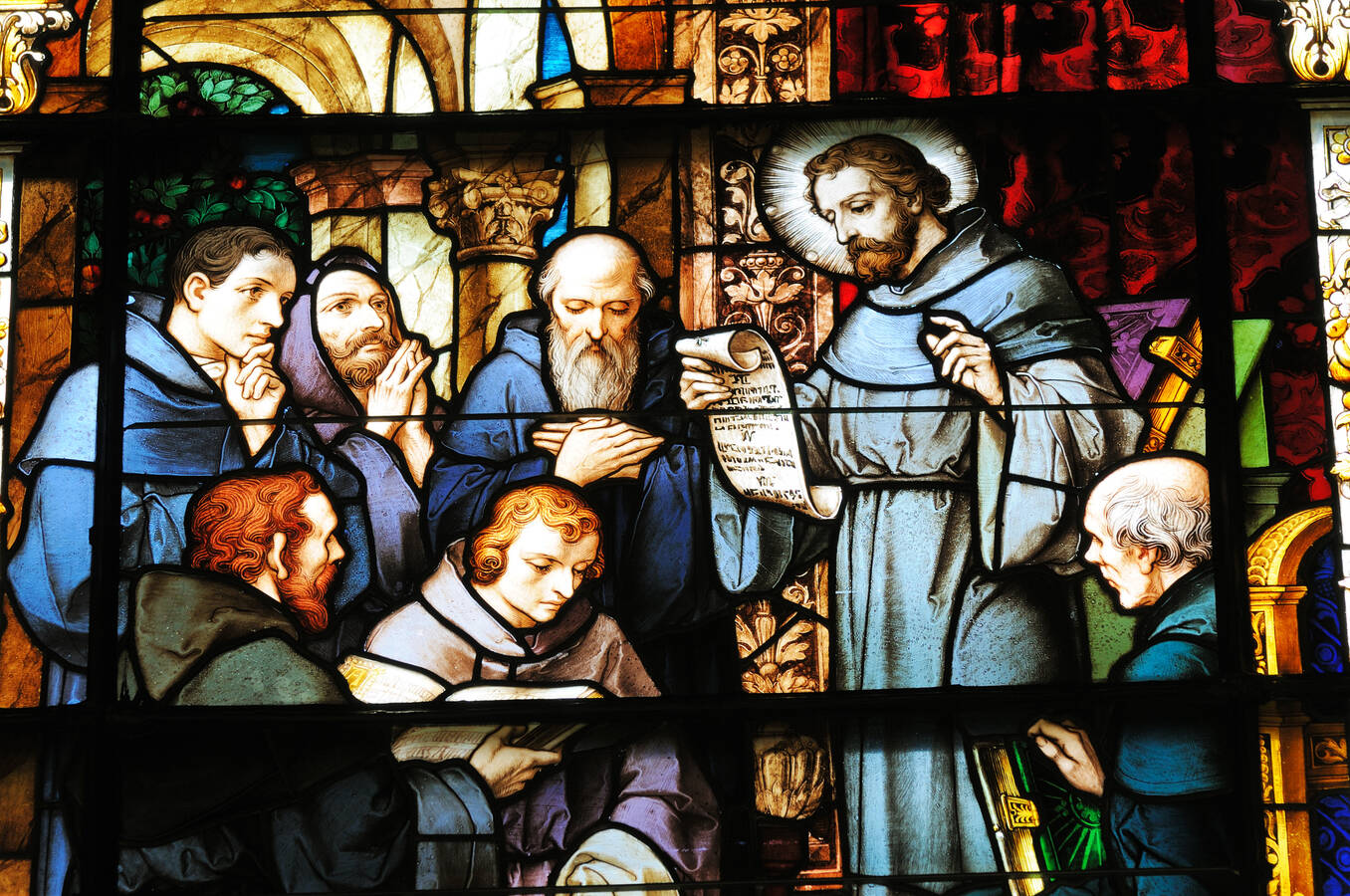

A new academic opus from a once-familiar name: Foucault

Contrary to the accepted narrative in secular histories, early church fathers did not repress sexuality. Instead, they granted it a central place in their understanding of what it means to know oneself. This is one of the main takeaways from the recent posthumous publication of Michel Foucault’s fourth volume of The History of Sexuality, subtitled The Confessions of the Flesh (Histoire de la Sexualité 4: Les aveux de la chair). (The book is available in French but has not yet been published in English.)

Michel Foucault (1926-84) was a French philosopher who studied the relationship between power and knowledge and the way it has changed throughout time. He paid attention to how practices of exclusion and domination are closely linked to authoritative claims of knowledge. The major foci of his work were the histories of madness, the social sciences, penitentiaries and sexuality.

The History of Sexuality is a project that occupied Foucault at the end of his life. He got to see only the first three volumes published. The first, subtitled The Will to Knowledge, begins by questioning what Foucault calls the “repressive hypothesis.” According to this hypothesis, sexuality was for the most part repressed before the various sexual liberations of the 20th century. Foucault does not deny that our present age softened some of the prohibitions of previous eras, but even with this liberation, Foucault remains suspicious of the role that this “repressive hypothesis” plays as a discourse in today’s sexual practices.

According to Foucault, the Church fathers did not really invent any new restrictions in matters of sexuality. They largely inherited the regulations of the Stoics and the ancient Greeks.

The person who invokes the repressive hypothesis sees him- or herself as freed from an oppressive past. This is not only a very simplistic vision of history; it also does not encourage much examination of one’s actions. Power is not only prohibition; it is also production. Sexual liberation has produced new sexual practices, and it is this productive form of power that the repressive hypothesis leaves unexamined. Even with liberation, sex continues to be a problem. Today’s debates about how to interpret all the practices that enter into the “gray zone of consent” exemplify how sexual practices can be problematic even in a supposedly liberated culture.

Historically, sex has not always been seen as an enigma to be deciphered. The History of Sexuality is an account of the hermeneutic problems that have been ascribed to sexuality throughout the ages. Originally, a draft of Volume IV was to precede Volumes II and III, but very “quickly...Foucault decide[d] to go further back in time to grasp, within Christian history, the point of origin...of the subject’s injunction to verbalize a truth-saying of himself.” The church fathers developed a number of practices for dealing with sexuality. But before diving into them, Foucault studied the preceding periods to better understand the specific transformations Christianity introduced.

For the fathers, the notion of sexual desire (concupiscence, libido) brought together a network of practices and discourses. “Spiritual combat,” “the examination of conscience,” virginity (celibacy) and marriage are some of these. For the fathers, sexual desire was a problem in that it escapes our will. Foucault sees in these early Christian writings a series of reflections about what is voluntary and involuntary in relation to sexuality.

In Volume IV’s first few paragraphs, Foucault states that the fathers did not really invent any new restrictions in matters of sexuality. They largely inherited the regulations of the Stoics and the ancient Greeks. What interests Foucault throughout the book are the specific transformations carried out by the early Christians in their appropriation of these “pagan” norms.

The book comprises three parts with four appendices. The first part is called “The Formation of a New Experience.” This new experience is that of the flesh as a source of “knowledge and self-transformation in function of a certain relationship between the cancellation of evil and the manifestation of the truth.” In other words, the early church fathers developed a series of techniques, based upon an interrogation of the flesh, in order to discover the truth of oneself and to reject what hinders that. The flesh thus became a place of knowledge.

Most of this first part concerns the ritual of baptism as a rupture within one’s life. To remain faithful to this change, one must forever be in a state of self-vigilance. One technique taken from the Stoics is the examination of conscience. In the Stoic “examen,” the emphasis was on exterior actions: what was done right or wrong. In its Christian variant, the examen emphasizes the recognition and confession of one’s thoughts. It seeks to uncover the nature of these thoughts: Where do they come from? What actions do they encourage? Am I being deceived by someone?

Foucault points out how the discipline of celibacy required constant practices of self-vigilance in relation to sexual desire for it to function effectively.

This introspection culminates in a confession. In listening, the confessor or spiritual director not only guides the person, but helps her to discover the truth of her thoughts. The Christian examen thus develops a practice of intimacy. It inaugurates a turn inward to discover the truth of oneself and then to seek a certain validation in sharing it with someone else.

Much of this introspection and articulation centers on sexual desire. Thus, a form of subjectivity, based on desire, begins to appear in relation to virginity and marriage. In the book’s second part, subtitled “Being Virgin,” Foucault reiterates his point of departure: Christians did not invent the idea of virginity as a practice. They even borrowed some of the standard “pagan” arguments for celibacy, such as viewing marriage as an obstacle to an independent life. The originality of early Christian writers was to conceive it as a “privileged,” or special, form of life.

The fathers understood celibacy as privileged in that it presently enacts what awaits all Christians at the end of time. They saw it inscribed within salvation history. But Foucault points out how this form of life required constant practices of self-vigilance in relation to sexual desire for it to function effectively. Virginity thus represents a particular way of engaging with the problem of sexual desire.

Marriage deals with the same problem differently. In Part III, “Being Married,” Foucault does a close reading of certain texts of Augustine concerning marriage. The question for Augustine was how to see marriage as something good while maintaining a belief in a certain level of evil inscribed within sexual desire. Consent is one of the concepts Augustine introduces to try to grapple with this tension. To engage in sexual relations is to consent to that sexual desire which one cannot control. This marks a separation from the “pagan” practices of continence. In these, the accent was on avoiding excesses and achieving self-mastery.

In contrast, Augustine frames the problem around the self’s own will. “[N]on-consent does not consist in overcoming desire by casting away from the soul the representation of the desired object, but in not wanting it as concupiscence wants it.” The goal becomes to not consent to sexual desire, not so much in order to surmount it but to transform the very way one wills. This theme of consent/non-consent functions as a pedagogy of the will, in which the objective is to learn to want differently.

One could see this volume as conducting a genealogy of the vocabularies that have framed the conversations about sexuality throughout history, even to this day. Consent is one of these terms. Foucault finishes the book by saying: “[t]he problematization of sexual conducts...becomes the problem of the self/subject.” Sexuality becomes linked with discourses and practices of self-exploration. For Foucault, two forms of subjectivity arise from all of this: one based on desire, the other on law. For the subject of desire, “the truth can only be discovered by himself, in the depths of himself.” As for the subject of law, his “imputable actions define themselves and are classed as good or evil according to the relationships he has with himself.”

One could see Foucault's final volume as conducting a genealogy of the vocabularies that have framed the conversations about sexuality throughout history, even to this day.

For better or for worse, it is clear that these two subjectivities have conditioned the rest of the history of Western sexuality. In today’s world, sex is for many a source of self-exploration. These two forms of subjectivity are still operant in contemporary conversations about sex where the ambiguities of consent are discussed. In terms of law, it can be seen in attempts at judging another person’s sexual behavior. This judgment does not stop at the level of the external actions committed. It seeks to uncover the interiority of the person being judged—i.e., his/her desires and intentions.

One cannot analyze the case of Louis C. K., for example, without making use of many of the categories that Foucault historically traces back to the church fathers: confession, consent, desire, finding the truth of oneself and more. Though one should not be too quick to look for answers for today’s #MeToo movement in The Confessions of the Flesh, it nonetheless provides a history of how the vocabularies that shape so much contemporary concerns emerged.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Story of Repression?,” in the Fall Literary Review 2018, issue.