Review: Dave Barry gets away with it

Seventeen-year-old me could think of no better life outcome than to be paid to read Dave Barry and then write about it. I first read Barry’s work in May of 1999 when a friend gave me a copy of Barry’s syndicated humor column. This particular article was in the form of a graduation speech that involved jokes about encyclopedia research, tattoo removal and wearing ducks as hats.

I was hooked.

I began reading Barry’s Miami Herald column weekly and then devoured his books, like Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits, Dave Barry Slept Here and Dave Barry Turns 40, for which I suspected I was not the target audience but loved anyway. I often cut out his columns from the newspaper and underlined the parts I found funniest, analyzing them in a profoundly unfunny way. Reading Barry’s work was one of the first times I recall laughing out loud at someone’s writing.

On the verge of adulthood, in the midst of applying to colleges and worrying about leaving my friends and family behind, it was a relief to simply read for fun and for that fun to come from stories of exploding whales. As I contemplated my future, Dave Barry gave me a strange sort of hope: You could get older and still get away with mind-boggling amounts of wackiness.

Barry’s latest, Class Clown: The Memoirs of a Professional Wiseass: How I Went 77 Years Without Growing Up, is a funny book with dueling subtitles that is a testament to the fact that Barry agrees with that sentiment. He thanks his loyal readers in the book, saying “they’ve enabled me to go for decades without having anything close to a real job.”

I am one of these loyal readers. I have always loved Barry’s appreciation of the absurd, from exploding toilets to the incendiary nature of Rollerblade Barbie to the hallucinogenic properties of certain toads. I recall eagerly awaiting his first novel, Big Trouble, which I described in a high school essay as “one of the most entertaining books I have read for a while although the characters did tend to swear a bit.”

I am able to quote this essay because, 25 years ago, as a senior in high school, I was required to turn in quarterly AP English “portfolios,” and my mother has not thrown a single one away. Each portfolio included a decorated manila file folder filled with printed samples of my best work, along with explanatory essays and introductions to offer context and reflection (or in my case, smart-aleck comments) about each piece.

From a structural perspective, Class Clown is not unlike my AP English portfolio. Readers of Barry’s latest will find enjoyable excerpts from many of his most notable columns, surrounded by additional memories, commentary and, occasionally, the perspective of hindsight. The book serves as both a victory lap and primer for Barry’s illustrious comedic career. Longtime readers will find many of the facts and events familiar. Readers who are new to Barry may benefit the most, as the book offers a number of guideposts for delving more deeply into his best work.

Admittedly, I may be more likely than most to find Barry’s stories familiar. One of the assignments included in my final portfolio was something our teacher called a “saturation paper,” which required us to immerse ourselves in the life of a famous person and write an essay from that person’s perspective. After considering Bruce Springsteen, Mankind (a professional wrestler in what was then the W.W.F.) and Kermit the Frog, I settled on my favorite syndicated humor columnist.

I titled my essay “Dave Barry: Books, Beer and Boogerbrains” and wrote it from the imagined perspective of Barry looking back on his life while waiting to be awarded his Pulitzer Prize for Commentary in 1988. I am sure Barry appreciated receiving the award, but I also loved the convenience of pointing to it whenever anyone questioned my literary taste. If Barry’s humor was good enough for the Pulitzer judges, who was I to second-guess them?

Barry’s tone in ClassClown is consistent and, at times, sophomoric, but as he has often said: “Sophomoric is often used as a pejorative term, but I myself remember laughing pretty hard as a sophomore.” He covers flaming Pop-Tarts, his early work teaching writing to businesspeople, and getting assignments from Gene Weingarten of Tropic, the Sunday magazine of the Miami Herald, where Barry’s humor career took off (all of which I can proudly say I also covered in my saturation paper).

In my introduction, I wrote that “the research does not really seem like work,” because it mostly involved reading books I was already excited to read. Although it also included driving to the public library and poring over the periodical index in order to track down a Playboy interview with Barry on the library’s microfilm (text only). But even as I worked for hours and wrote pages of text, I felt I was getting away with something.

This is a sentiment Barry often echoes in Class Clown with regard to his own career. He can barely believe that he has been allowed to do what he does for as long as he has. His lack of self-seriousness about his work has always been part of his charm. Barry’s writing is smart and incisive, but often simply silly for the sake of it. He writes in the book that readers have told him his work makes the world a better place, because, they claim, “in troubled times humor is vital.” But Barry admits that “I’d probably be doing this even if it made the world a worse place. It’s pretty much the only thing I know how to do.”

Barry’s relationship with his readers, those he infuriated and those he enchanted, provides some of the most delightful memories in Class Clown. (His supporters included—and I am not making this up—Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.) Readers often sent him crazy news stories for possible column fodder, and for years Barry responded with a postcard that read, “This certifies that [name] is an Alert Reader and should seek some kind of treatment immediately.” Barry writes about this in the book, but I also know this because I once received such a postcard.

After I became a fan of the Florida-based Barry, I learned that a Massachusetts man by the name of Dave Barry was running for selectman in a small town near my hometown. I hoped to share this news with the Florida Barry, who had launched his own satirical campaign for president. Knowing this, some of my friends obtained (definitely not by stealing it) a yard sign for Selectman Barry’s campaign and proudly presented it to me. Not wanting to mail a giant sign to Florida, I instead did what any self-respecting teenager of the 90s would do and took a careful photograph of it with my film camera, had the film developed at CVS and sent the glossy picture of the campaign sign to the Florida Barry via the U.S. Postal Service.

In response, I received Barry’s standard reply, with one meaningful modification. Below Barry’s signature, he had written: “Select Man.” I was delighted by this small, personal touch. Many months (years?) later, I stumbled upon an online photo tour of Barry’s office at the Miami Herald. In my memory, the postcard was taped to the front of his office door. After all the laughs he’d provided me, the little sign felt like an inside joke with a friend. This is what good humor does: It keeps you company, makes you feel a little less alone.

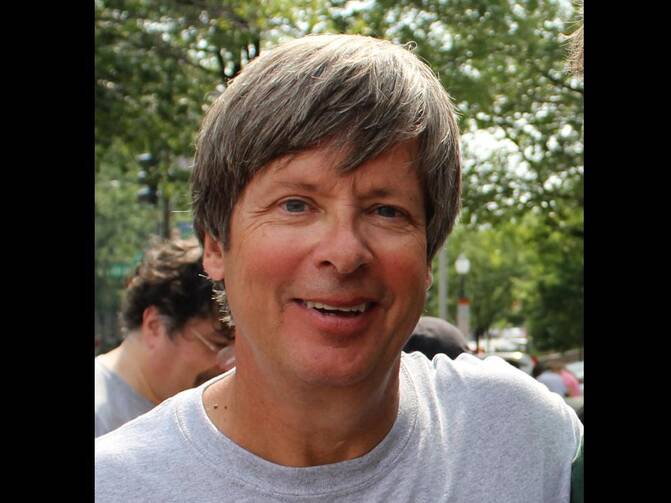

At the end of my senior year, in the folder containing my final English portfolio (25 years ago!), I tucked a printed copy of Barry’s graduation-themed column behind my own work. I also included a grainy, black-and-white photo of Dave Barry playing an electric guitar in pajamas and a robe. The handwritten caption read, in part: “He will always make me laugh.” Seventeen-year-old me would be happy to know this is still true.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Getting Away with It,” in the July/August 2025, issue.