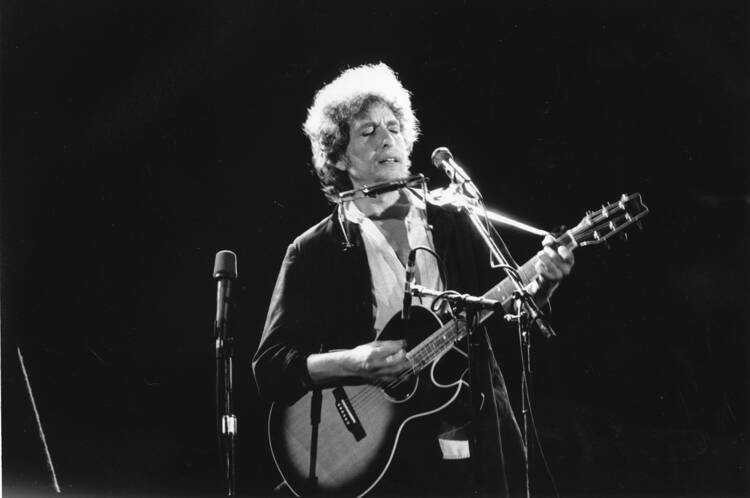

The strangest teacher I had in college turns 80 years old on May 24. And after 39 studio albums, Bob Dylan shows no signs of stopping.

Growing up, I would have laughed at the suggestion that I would one day call myself a Dylan fan. I have no memory of hearing a Dylan song before my sophomore year of college, and the few of his early songs I heard that year didn’t make much of an impression on me. I associated Dylan with hippies, something I had no interest in, and what little I heard did not do much to get me beyond my stereotype: seemingly mediocre voice, outdated sound, lyrics at times verging on nonsensical. Overall, Dylan seemed to me a taciturn court jester of a bizarre and bygone era, one of the many voices in the background noise of my college years, that wouldn’t affect my life in any meaningful way.

That changed. I eventually came to realize there was nothing wrong with Dylan or his music; I just wasn’t ready to hear it. The state you are in when you hear music is often just as important as the substance of the music itself. I had to travel before I could really hear what Dylan was about; had to feel the movement that Dylan felt as he wrote his songs. And that summer before my junior year, movement is what I got: a month-long class in Mexico, two weeks on the road across America and a four-day bus trip back, all the way from Seattle to New England.

Dylan's raspy tone and earnest rhythmic phrasing deliver timeless stories and vintage Americana; always moving, always searching.

I returned to college feeling strong, the movement in my body and the land in my soul. For a brief period, I had the strange feeling that I had absorbed all of America. And when a roommate played his new CD, “Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. III,” that is what I heard: seamless layers of folk and blues, bop prosody and country, all infused with a growing tinge of gospel. The raspy tone and earnest rhythmic phrasing deliver timeless stories and vintage Americana; always moving, always searching, even when the exuberance for life gives way to the poignancy of ending worlds.

At first, I didn’t hear the music so much as feel it: the way it all seemed to hover over the land, weaving the different regions and centuries into one song, taking all of America on board and leading it on a journey to find itself. “We’re going all the way,” proclaimed Dylan—in “Brownsville Girl,” co-written in 1986 with the playwright Sam Shepard—and then he showed how far:

til the wheels fall off and burn

til the sun peels the paint

and the seat covers fade

and the water moccasin dies

I was back on the road.

I began to realize that I had only glanced off the surface of Dylan’s art. The sound got me past his clownish image. I began to hear the words. It took time for me to grow into; to fully enter into the worlds created by his songs. My friend G, who was raised a Buddhist in Sri Lanka, gave me the first signpost:When his CD came to Track 7, “Dignity,” he gave a shout of approval and cranked up the volume. After a while I asked him why he liked that song so much. “Dignity,” he replied matter-of-factly, as if surprised that I didn’t already know. “That’s what life comes down to.”

Though confused, I nodded. I didn’t have the words but I sensed that Dylan was something like Bob Marley, whose life and body of work added up to something that gave a much deeper vision of truth than the separate parts. Where Marley’s messianic vision of justice and redemption was global, Dylan honed in on the uniquely American manifestation of truth: the westward-looking, forever youthful ability to constantly reinvent oneself. Where Marley’s “Exodus” reordered the world’s colonial contradictions, Dylan led America on a quest to find itself and along with it—truth. Where Marley conjured faith as a plain-sense reality, Dylan showed how to dance through postmodern ambiguities with faith intact.

Dylan honed in on the uniquely American manifestation of truth: the westward-looking, forever youthful ability to constantly reinvent oneself.

I didn’t ask any further questions and my friend didn’t say more; we just allowed Dylan’s words to teach us, meditating on dignity and everything that came with it. “On a song like this, there’s no end to things,” Dylan wrote in his memoir, Chronicles Vol. I, about composing “Dignity.” “Love, fear, hate, happiness—all in unmistakable terms, a thousand and one subtle ramifications.”

It was not until I read Chronicles 15 years later that I started to see more fully how Dylan was teaching us. “Dignity” and all of Greatest Hits Vol. III were to us exactly what folk songs were to Dylan when he was our age. A “parallel universe,” Dylan called them, “with more archaic principles and values; one where actions and virtues were old style and judgmental things came falling out on their heads.... clear—ideal and God-fearing.” Those folk songs for Dylan were “a reality of a more brilliant dimension,” “life magnified” and, as Dylan said, were “the way I explored the universe.”

That was true of us too: We explored the universe through all his songs but particularly through “Dignity.” Dylan was pursuing dignity but didn’t tell us exactly what it was; he showed us how to search for it, gave hints and laid bare his own mistakes. We didn’t have a way to express the deepest questions of human suffering but Dylan did and we were studying his words—words beaten out on drums, sliding like the pedal steel guitar, stretched like his harmonica notes, steady as the clack of the train tracks, the words bending and flowing with the curve of the road, layered with meaning like clouds on the western horizon flaring at sunset, words like those of the folk songs Dylan listened to; that work “on some kind of supernatural level.”

It is not accidental that it is Dylan’s material after his conversion experience that has the greatest supernatural power. A failing marriage and non-stop touring broke down many of the certainties in his life and spurred him toward another transformation: In 1979, he became a Christian. For the next three years, he spoke in a bold evangelical voice and put out his three “Christian albums.” Some time around 1983, Dylan shapeshifted again, abandoning his straightforward preachiness, but his songs continued to ruminate on faith in myriad ways.

This world might feel like a series of dreams—but Dylan reminds you: You hold cards from another world.

These songs—spiritual journey songs without explicit reference to Christianity—made up the majority of the songs on Greatest Hits Vol. III. I didn’t know the details of Dylan’s life history back then or that he had experienced a deep encounter with Christian faith; I just felt it. You can’t hear “Ring Them Bells” and not feel it; the wrestling with faith and pursuit of truth in a distinctly Jewish-Christian key. Truth seems at first to give an easy, singular answer to every question. But what does it mean, Dylan asks, in an ever-expanding, ever-changing world for an ever-changing, ever-expanding self? It means many answers that require searching and struggle and the acceptance of living in an unpredictable, liminal space. The world is on its side and time runs backwards. Yet despite this, the bells ring in the night and the Center holds.

This is the crucial facet of Dylan’s voice for me, the integrative work he does in these songs: taking facts and weaving stories, drawing out concepts and meaning, and issuing forth prayer: like the Buddhist process of moving from the rule of the Dharma to the reality of Samadhi. I and the others I knew who gravitated to Dylan in their college years needed this work. Education that is not focused on preparing you to fulfill a specific role can often feel chaotic and leave students scattered. This is even true—or maybe especially true—of a justice-focused Catholic liberal arts curriculum designed to open you up to the full spectrum of knowledge and the world’s problems. Expanding your vision unmoors you from what you took for granted and leaves you without firm ground to stand on. Dylan’s songs, along with those of Bob Marley and Tupac Shakur, the other two great musical voices of my college experience, filled in that gap and provided a unitive center. Marley appeared first and bestowed a holistic vision of faith. Tupac was last, taking on the temptation of power and death.

Dylan came second and provided a life lived on the ground, a particularly American life, where the rubber could meet the road. What I learned most from him is that since the world and the self are ever-expanding and changing, truth needs to be experienced, lived, to be understood.

“Greatest Hits Vol. III” turned out to be a blueprint for our next few years after graduation. Search everywhere, Dylan said—the border towns of despair, the land of the midnight sun, the valley of dry-bone dreams and everywhere in between—and we followed the lyrics as if they were instructions for chasing down dignity, not in the sense of finding a solution to an equation but in the sense that mystery gives way to an enduring truth.

Dylan’s longevity and repeated reinvention means he stays with you. The search for dignity often doesn’t turn out the way you hope. Youth fades—and you are hurled into other paths. Dylan doesn’t disappear—but shapeshifts you into another form for each new stage of the journey. This world might feel like a series of dreams—but Dylan reminds you: You hold cards from another world. The end of a road doesn’t mean the end but a rebirth, the often painful shedding off of one more layer of skin. But despite the liminality, the Center will hold.

Happy Birthday Bob, and keep on searching. Like you said: We’re going all the way.

More from America: