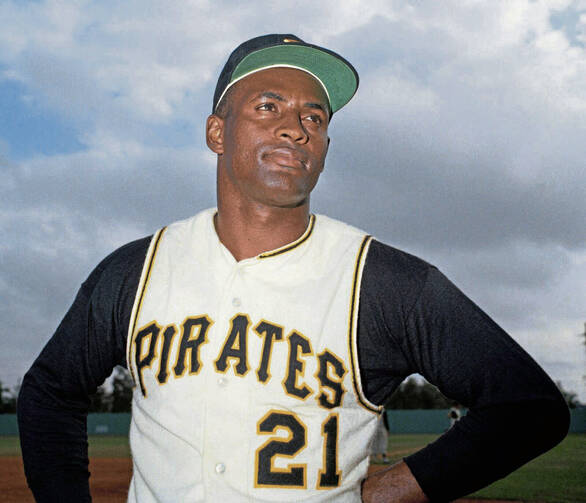

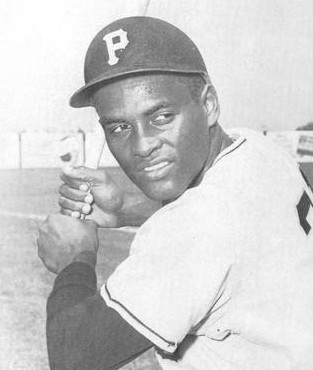

On Oct. 13, 1960, the Pittsburgh Pirates defeated the New York Yankees in the seventh and deciding game of the World Series, on a home run struck in the bottom of the ninth inning by the young second baseman Bill Mazeroski. The Pirates’ emerging superstar, right fielder Roberto Clemente, hit safely in all seven games while fielding, throwing and running the bases with a ferocious passion. Clemente lost out in the balloting for the Series’ Most Valuable Player award to Yankee infielder Bobby Richardson, the first time a member of the losing team had won. The following month, Clemente finished eighth in voting for the regular season MVP: a pair of solid but not stirring Pirate teammates—who like Richardson, happened to be white—finished first and second.

The world champion Pirates were honored by a local civic group at a restaurant near the club’s Florida spring training headquarters in February 1961. The guest list included “several heroes of the World Series,” wrote David Maraniss in his 2006 biography, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, “but not Clemente, who could not get into the building unless he worked as a waiter or dishwasher.” A Black man from Carolina, Puerto Rico, Clemente “detested any response to Jim Crow segregation that made him seem to beg.” He had previously told Black and Latino teammates that “anyone who begged for food would have to fight him to get it.”

Major League Baseball celebrates the legacy of Roberto Clemente on Sept. 9.

Clemente believed the systemic racism of Jim Crow tainted everyone who cooperated with it, including Major League Baseball club owners. “Later, when asked to list his heroes,” Maraniss noted, “Clemente would place Martin Luther King Jr. at the top of the list [King would visit Clemente at his farm in Puerto Rico during a mid-1960s off-season]. He supported integration, the norm in Puerto Rico, and believed in King’s philosophy of nonviolence. Yet in some ways his sensibility brought him closer to Malcolm X,” who had recently asserted: “To beg a white man to let you into his restaurant feeds his ego.”

Though he was born a U.S. citizen in 1934, Roberto Clemente was treated by most sportswriters on the mainland as a “foreigner”; he took pains to answer questions in proper English, only to see his speech rendered in print as phonetic caricature. Yet he was enormously popular among a cadre of young baseball fans whose eclectic makeup—male and female, Caribbean and Western Pennsylvanian—hinted at shared affinities for his personal authenticity and unique style of play. I enlisted—as a 7-year-old parochial school first grader—moments after gazing on Roberto for the first time from the right field grandstand at Pittsburgh’s ancient Forbes Field—on a drizzly May night in 1963—when the Pirates hosted the American League’s Cleveland Indians for an unofficial “exhibition game.”

Clemente endured a chronic struggle with his creaky neck, captured by the Beat poet Tom Clark:

Rearing his

head back

on his neck

like a proud horse

At the plate, Roberto stood deep in the batter’s box and far from the dish. His swing was composed of clashing body parts: The back end spun away from his torso and toward the pitcher’s mound. Turning on the pitch, he planted all his weight on the left foot—leaving his back foot dangling loose above the dirt—while whipping his arms and torso at the ball with a wild man’s lunge. The laws of physics removed all hope of his reaching a pitch low and on the outside corner of the plate, yet the veteran Cincinnati Reds second baseman Tommy Helms once testified that the hardest-hit ball he ever fielded was an opposite field rocket off Clemente’s bat, on a pitch to that very location.

Deep in the pillared shadows of the grandstand that night I shivered with joy and anticipation; mistaking it for a chill, my father drove us home before the game ended. Several weeks later we moved to Southern New England: Clemente and the Pirates moved along with me via the 50,000 watts of clear Channel KDKA radio airwaves; on sultry summer evenings handfuls of Pirates fans scattered across 38 states and Canada tuned in to KDKA and the Voice of the Pirates, “the Gunner,” Bob Prince, who called nearly all of the 2,433 regular season and 26 postseason games in which Roberto Clemente suited up in his Pirates uniform.

We all reveled in Clemente’s balletic grace and the virtuosic timing of his sprinting, sliding catches, from the power alley in right-center field to the foul territory along the first base line.

I saw one live Pirates-Mets game every summer at Shea Stadium in Queens, always on a weeknight in June. As the 1960s deepened, I noticed Clemente fans more ardent and numerous gathering at Shea, drawn largely from either New York City’s expansive Puerto Rican community or—less predictably—from the ranks of the Big Apple’s ragtag countercultural sectors. We all reveled in Clemente’s balletic grace and the virtuosic timing of his sprinting, sliding catches, from the power alley in right-center field to the foul territory along the first base line. At one game a kid seated in front of me sporting a long reddish ponytail and braces exulted: “Man, he really got on his horse for that one!”

Roberto Clemente had quietly entered a creative pantheon I discovered only after his death, stumbling upon a poem by East Orange, New Jersey’s Michael Lally, “My Life,” featuring a lament for deceased geniuses (in consecutive order) Jack Kerouac, Eric Dolphy and Roberto Clemente—my favorite writer, musician, and lifelong, god-like hero, respectively. Residual anger lent a kind of existential frisson to Roberto’s competitive ferocity. “When Clemente was on the go,” as David Maraniss explained, “it seemed not so much that he was trying to get to a base as to escape from some unspeakable phantasmal terror.”

He was driven by the volatile mix of joy and rage that marked this signal cultural moment of the mid-to-late 1960s. If charted on a spectrum, Clemente would occupy the more joyous end, but the jagged edge of his tumult was impossible to conceal, evoking the great Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar’s observation on first hearing the late recordings of saxophonist John Coltrane: “I felt you were crying out through your instrument and it was like a shriek of a tormented soul...pain and the hurt of generations comes out.”

Roberto Clemente was unique for sustaining the basic spiritual beliefs he imbibed from his Baptist mother as a child (“Any time you have an opportunity to make a difference in this world and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on Earth.”), and for the gifts of healing, his practice of which became integral to the Pirates’ clubhouse culture. “It was something...supernatural,” attested Roberto’s wife Vera Clemente. Roberto was also blessed by the gifts of his teammates. By 1971, the Pirates were not simply the best team in the National League, they were the most ethnically and racially diverse outfit in the history of American professional sports, boasting athletes not only from America’s inner cities and rural small towns, but from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico and Panama.

On Sept. 1, 1971, early in a game against the Phillies in Pittsburgh, the young second baseman Dave Cash turned to outfielder-first baseman Al Oliver—a supremely talented Clemente protégé—and observed: “Hey Scoop, we got all brothers out there.” “We sure do,” Oliver replied. Twenty-four years after Jackie Robinson broke the national pastime’s sacrosanct color line, 11 years after Roberto Clemente stood alone as a person of color in the starting lineup of the 1960 championship team, the Pirates had fielded the first all-African American and Black Latino starting lineup in Major League Baseball history. Following another Pirates win, Danny Murtaugh—the Buccos’ Irish American manager—was asked by a local reporter if he even realized that all nine starters were Black. Murtaugh did his best to feign surprise: “Did I have nine blacks in there? I thought I had nine Pirates out there on the field.” The human dignity enshrined in these nine Pirates was Roberto Clemente’s greatest sporting legacy.

The human dignity enshrined in these nine Pirates was Roberto Clemente’s greatest sporting legacy.

As the 1971 World Series loomed, “[H]ere came Clemente, at age thirty-seven…fueling himself with the anger of an underappreciated artist,” Maraniss wrote. His old friend and compatriot José Pagan was treated to a disquisition on “precisely what [Clemente] would do to win the championship for Pittsburgh” against the Orioles; perhaps Roberto added a bonus prophecy of the veteran Pagan’s contribution (a ringing double to left in the eighth inning of Game Seven, driving in the Series-winning run in the lumbering person of Willie Stargell, who circled the bases from first to home on a hit-and-run play like a freight train). As for Clemente, the preeminent baseball writer Roger Angell of the New Yorker left Baltimore satisfied that Roberto’s performance throughout the series approached “something close to the level of absolute perfection.”

Moments after the final out of the deciding game, Clemente spoke into a microphone held by Bob Prince: “Before I say anything in English, I would like to say something for my mother and father in Spanish: ‘En el día más grande en mi vida, para los nenes la bendición mía, y que mis padres me den la bendición desde Puerto Rico’.” (“On the proudest day in my life, to my children I give my blessing, and from my parents I ask their blessing from Puerto Rico”). This was among the most powerful private moments ever witnessed in public, by a global audience that numbered in the hundreds of millions. In December 2004, Bronx native Julio Pabon told David Gonzalez of the New York Times: “To hear it that day was like an out of body experience.”

Roberto Clemente died on New Year’s Eve in 1972 when a badly overloaded DC-7 cargo plane laden with relief supplies for Nicaraguan earthquake victims crashed with him on board. Clemente “was taken away from a community that is still in search of itself,” Pabon lamented to Gonzalez in 2004. “As Puerto Ricans, we are still not defined as a country or a state. We are in limbo.” Yet the narrative of Clemente’s death needs to be separated from his legacy as a self-sacrificial humanitarian. David Maraniss was the first to detail the many ways in which the crash was not a tragic accident, but the result of multiple instances of criminal negligence, enabled at least in part by a habit of indifference or disdain toward Puerto Rico and its people. Federal officials, industry regulators and operatives in the “dark little corners” of rogue aviation companies served the Puerto Rican people badly, sometimes as a function of racial and ethnic profiling.

Roberto Clemente should never have been relegated to board a death trap with wings in order to bring help to others. The path of greatest integrity for honoring Roberto is through continued examination of his life circumstances and the histories of his homeland and region, recovery of the creative resources he left behind, and a renewed commitment to fostering the goal of human equality that Roberto Clemente pursued with the same passion he brought to the baseball diamond.