Review: When musicians go from outliers to icons

This nearly 500-page treatise on the agitational power of popular music in society, history and culture finds its author, the award-winning writer and musician Ted Gioia, at the height of his critical power. Gioia establishes the connection between music and violence—from the universe-defining explosion (and “downbeat”) of the Big Bang to the music-driven hunting rituals of the Paleolithic era to the inner-city violence depicted by late-1980s gangsta rap. He also argues that the most significant musicians and composers throughout history have suffered rejection by the “cultural elites” of their day, only to be sanitized and elevated by those same elites after death.

Gioia opens Music: A Subversive History by stating that the term “music history” makes him cringe, with the “images of long-dead composers, smug men in wigs and waistcoats” that it conjures up. It is clear that Gioia wrote this book for readers who might feel the same—who would be more at home at Coachella than at Carnegie Hall. Or perhaps more accurately, readers who might find themselves drawn to both settings. But, he argues, so would have rabble-rousers like Mozart or Bach.

Bach, Gioia writes, “is commemorated as the sober, bewigged Lutheran, who labored for church authorities and nobility,” but he was far more colorful. Bach’s exploits were well known while he lived, including “pulling a knife on a fellow musician during a street fight” and “consorting with a married woman in the organ loft.” It wasn’t until a decade after his death in 1750, a period that coincided with the rise of German nationalism, that “the mythos of Bach’s genius finally emerged.”

It is clear that Gioia wrote this book for readers who would be more at home at Coachella than at Carnegie Hall. Or perhaps more accurately, readers who might find themselves drawn to both settings.

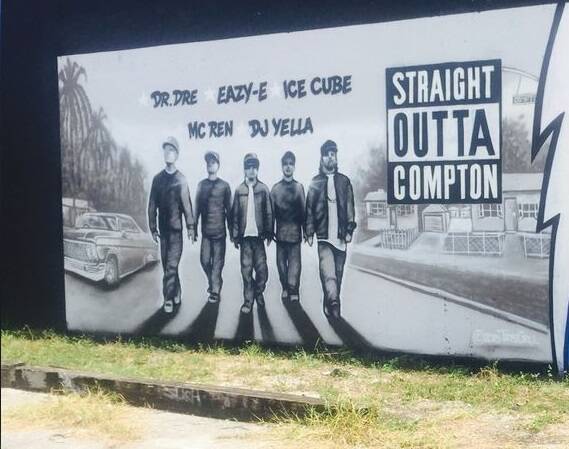

Though Gioia’s examples of this mainstreaming process—from outlier to icon—are many, what I found most emblematic of his argument was his consideration of N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton”—an album that went from pariah to paragon in 25 years. When it was released in 1988, the gangsta rap album was maligned by pundits, repressed by on-air D.J.s and even reviled by the F.B.I.—who sent a threatening letter to the group’s record label. But in 2017 it was chosen by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry, “a distinction limited to works of cultural, historical, or artistic significance.” As a postscript to this anecdote, Gioia writes that the F.B.I. letter is now on display at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame—as “a monument to the futility of authorities’ attempts to control the evolution of the song.”

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “From outliers to icons,” in the July 2020, issue.