The Faith of Jimmy Carter

When Billy Graham died in February at the age of 99, commentators offered dueling perspectives. Was the world-famous evangelist “the last high-profile bipartisan evangelical,” as some eulogized? Or had America’s Preacher started a strain of Gospel-infused white nationalism that still exists today?

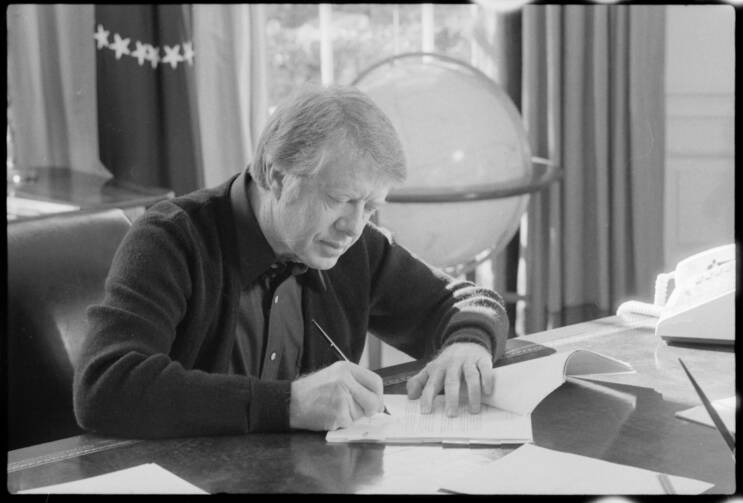

But if Graham is either the foil or forefather of current evangelical politics, then Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States, is the road not taken. Today it may seem inevitable that evangelicals gravitated to the Republican Party in the 1980s; but Carter, the wealthy peanut farmer from Georgia who won the 1976 election as a Jesus-loving Democrat, complicates the story. Like the evangelical politicians who succeeded him, Carter talked about his “personal relationship with Jesus Christ” (and famously confessed to Playboy magazine, “I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times”). Yet as other evangelicals drifted to the religious right, Carter advocated universal health care, proposed cuts in military spending and denounced the tax code as “a welfare program for the rich.”

Voted out of office after his first term, Carter has dedicated himself to humanitarian work through the Carter Center, the nonpartisan human rights organization he and his wife founded in 1982. But Carter, now 93, remains adamant about the role of Christians in the political sphere. “I believe now, more than then, that Christians are called to plunge into the life of the world,” he writes in Faith: A Journey for All, “and to inject the moral and ethical values of our faith into the processes of governing.”

Jimmy Carter: “I believe now, more than then, that Christians are called to plunge into the life of the world and to inject the moral and ethical values of our faith into the processes of governing.”

The goal of Faith: A Journey for All, as Carter states loftily in the Introduction, is “to explore the broader meaning of faith, its far-reaching effect on our lives, and its relationship to past, present, and future events in America and around the world.” Fortunately, the book is far less stuffy than such a description suggests. Peppered with stories from Carter’s political career and quotations from theologians, Faith is the religion-infused appeal of an elder statesman to the country he once governed. Though Carter’s evangelical faith is on full display, his appeal to readers is religiously neutral. Whether through the Bible, the Quran or the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Carter entreats his fellow citizens to draw on “these visions of improved human interrelationships...to meet the challenges of the present moment.”

These challenges weigh heavily on Carter. Two paragraphs into the Introduction, he resorts to italics to remind readers the threat of worldwide nuclear annihilation “still exists.” By the last chapter, Carter’s concerns about the United States include its reliance on military might, refusal to outlaw assault weapons, acceptance of oligarchy, inaction on climate change, skyrocketing levels of incarceration and intensified polarization. Yet his tone—and message—is optimistic. “I still have faith that the world will avoid self-destruction from nuclear war and environmental degradation,” writes Carter, “that we will remember inspirational principles, and that ways will be found to correct our other, even potentially fatal human mistakes.”

The source of his optimism is faith, including his “broader” faith in the American people as well as his religious faith in God. To a degree some will find surprising, Carter’s religious faith is deeply relational: “To me, Jesus Christ is not an object to be worshipped but a person and a constant companion,” he writes. Through this relationship with God, Carter feels known, understood and loved. And this loving relationship with God has given Carter a “pleasant feeling of responsibility” to share that love with others, including his work on behalf of human rights. When people from different parts of the world work together “as equals,” explains Carter, they experience “an instant and overwhelming melding of cultures, languages, and interests into a spirit of friendship and love.”

The sociologists Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith identify this relational impulse as a defining characteristic of white American evangelicals. Yet as they explain in their 2000 book Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America, this worldview often leads white evangelicals to believe “there really is no race problem other than bad interpersonal relationships.”

Carter makes this mistake. Though his faith instilled in him an absolute conviction that racism has no place in American society or churches, Carter sees racism primarily as something that happens when people “assume a superior relationship to others” and thus suggests relational solutions. After criticizing religious congregations for failing to address “the racial and social barriers that still divide us,” he asks: “How many of us white people actually know a poor black family well enough to have a cup of coffee in their living room or kitchen? Or know the names of their teenage children?”

Building interracial friendships is good, explain Emerson and Smith, but this “let’s be friends” approach favored by many white evangelicals does not change the structures that perpetuate unequal access to health care, quality education, political power and wealth. “Present-day white evangelicals attempt to solve the race problem without shaking the foundations on which racialization is built,” they write. “As long as they do not see or acknowledge the structures of racialization, they inadvertently contribute to them.”

Which brings us to the current occupant of the White House. Carter never mentions President Trump by name and only once criticizes “the president” directly for his “irresponsible and uncontrollable public statements and tweets on social media.” Yet Carter uses some of the strongest language we have heard from any of our past presidents to deliver a fiery critique of the 2016 election. During that election, writes Carter,

The existing trend toward control of our democratic system of government by a small group of powerful and wealthy citizens and corporations was enhanced and solidified, false and illogical political claims have been rampant, ad hominem attacks on political opponents became normal and accepted, and serious allegations are being investigated about direct Russian involvement and interference in the electoral process.

In short, he believes that our faith in the government, democracy, and the “basic principles of justice” have been threatened.

But then comes a plot twist. After summarizing the political issues he finds most distressing, Carter pivots: “Most church members are more self-satisfied, more committed to the status quo and more excluding of dissimilar people than are the political officeholders I have known,” he writes. “In considering these issues, many congregations are more like spectators than participants, usually waiting for an aggressive pastor or professional staff to inspire any corrective programs in their local communities.”

Jimmy Carter: “Civil disobedience is in order when human laws are contrary to God’s demand.”

Carter then does what he failed to do when addressing race; he calls on people of faith to stop being “spectators” and start challenging injustice. “What is the proper response from people of faith when there is an obvious disparity between our government’s policies and our religious beliefs?” asks Carter. Several sentences later, he answers: Look to the example of Jesus and his disciples, who demonstrated that “civil disobedience is in order when human laws are contrary to God’s demand.”

It is a radical conclusion. Despite his obvious displeasure about the current state of political affairs, the former U.S. president saves his most forceful criticism—and his strongest appeal to take action—for the church.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “An American Journey,” in the Spring Literary Review 2018, issue.