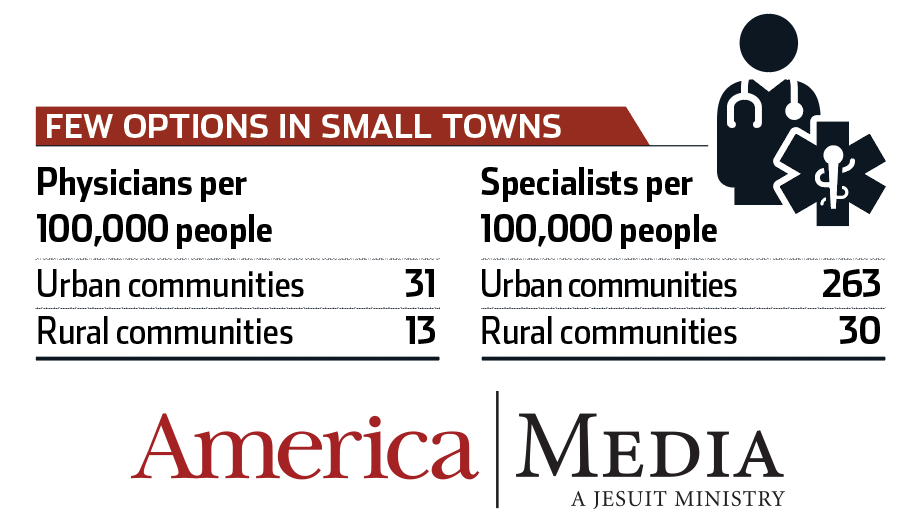

Where are the margins in U.S. health care? They can be tracked by race and ethnicity, highlighted on a map or charted along an income graph. In rural America life and death may be a matter of how far an injured farmworker has to be transported to reach emergency care. In a Rust Belt city where rates of depression and anxiety are reaching unprecedented levels, the opioid epidemic has been taking a shocking toll on white, blue-collar workers.

Income is perhaps the unifying indicator of health care in crisis across all the margins of America—a reliable predictor of lapses in insurance coverage, diminished access to health specialists and poor health outcomes from inadequate treatment for common illnesses—leading to the final measure of all: substantially lower life expectancy.

Mary Haddad, R.S.M., is the incoming president and chief executive officer of the Catholic Health Association. In July, Sister Haddad will succeed Carol Keehan, D.C., who has led the C.H.A. for 14 years.

Going to the margins is something that Catholic health care has always done, Sister Haddad said. “That’s where we started in Catholic health care in this country; it’s what we have given to this country,” she said, pointing to the association’s 19th-century origins in the work of religious communities in underserved immigrant communities in both rural and urban settings across the country. She affirms that her network’s membership is ready to do the same today.

Income is perhaps the unifying indicator of health care in crisis across all the margins of America—a reliable predictor of poor health outcomes from inadequate treatment for common illnesses—leading to the final measure of all: substantially lower life expectancy.

Spiking rates of income inequality have been accompanied by poorer rates of general health among vulnerable populations, and differences in life expectancy according to income quintiles have followed. The Health Inequality Project reports that the richest men in the United States live 15 years longer than its poorest, and the richest women live 10 years longer than the nation’s poorest women.

The chronically under-resourced Indian Health Service struggles to live up to treaty obligations that guarantee health care to Native American and Native Alaskan communities where health outcomes are among the worst in the nation.

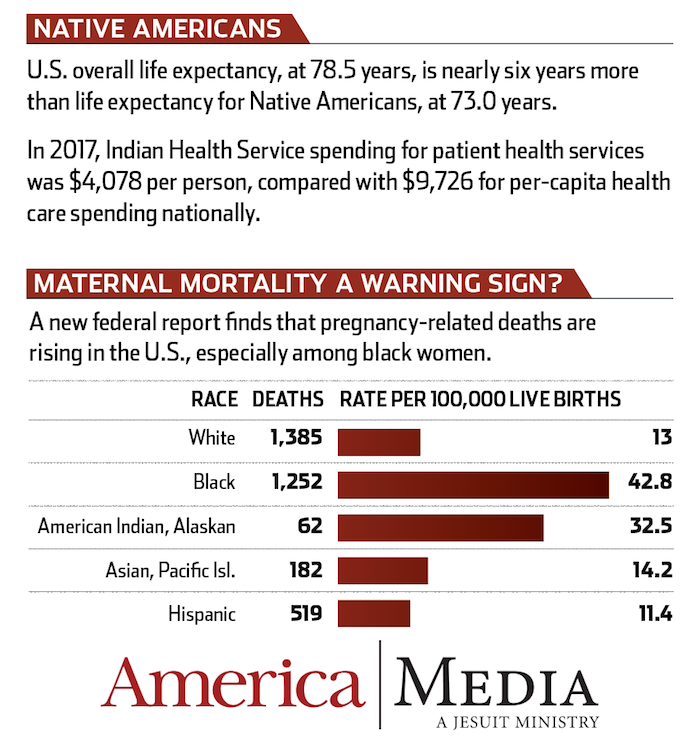

America’s indigenous communities suffer rates of acute illnesses that are substantially higher than those of other U.S. communities, and life expectancy in Native American communities is almost six years less than in the overall population—73.0 years instead of 78.5 years. Rates of accidental death and death because of influenza are more than double the general population; diabetes-related mortality is three times the national rate; and mortality related to alcohol abuse is almost seven times higher.

Globally, maternal mortality fell 44 percent between 1990 and 2015, according to the World Health Organization. But in the United States the trend has been moving in the opposite direction. Mothers die in 17 out of every 100,000 U.S. births each year, up from 12 per 100,000 25 years ago.

“An American mom today is 50 percent more likely to die in childbirth than her own mother was,” Neel Shah, an obstetrician at the Harvard Medical School, told the Associated Press.

Possible factors driving that unfortunate trend include the high C-section rates in the United States and soaring rates of obesity, which raises the risk of heart disease, diabetes and other complications during pregnancy. But race has also become a consistent risk factor.

African-American women suffer a rate of maternal mortality that is more than three times that of white women, and mortality among Native American and Native Alaskan women is 2.5 times the rate experienced by white women. More than half of the maternal deaths among African-American and Native American women are preventable, according to a report released in May by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Lisa Hollier, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, told The Associated Press the high mortality rate among African-American women may be partly attributable to racial bias they experience in receiving prenatal and delivery care—for example, doctors not appreciating risk factors more common among African-American women, like high blood pressure.

The chronically under-resourced Indian Health Service struggles to live up to treaty obligations that guarantee health care to Native American and Native Alaskan communities where health outcomes are among the worst in the nation.

Health care in the United States finds itself at a crossroads, according to Sister Haddad, reorienting itself from acute care, which now claims the lion’s share of the system’s resources, toward community health services focused on prevention and lifestyle modifications that prevent health crises in the first place.

Adjusting reimbursement structures from private and public payers that will finance that realignment will be critical, according to Sister Haddad. Despite the exorbitant cost of the nation’s health care delivery system, many not-for-profit institutions struggle to keep their doors open. Sister Haddad said that reimagining health delivery will mean turning fresh eyes to the true contributors of health problems. Acknowledging and responding to the social determinants of poor health must be integrated into contemporary health care, she said.

“We’re finally reckoning with the value of addressing social issues as well as clinical issues,” Sister Haddad said. It is a paradigm shift for C.H.A. members, who are now proactively “looking into how to incorporate that social component into health care.”

People seeking treatment today cannot be sent home with a prescription and vague instructions to address their illnesses, she explained. “You may not have a home,” Sister Haddad said. “And if you do, you may not have a refrigerator in your home to keep your medication cold.”

Catholic health services have begun to team up with social service providers to respond to patients’ total needs. “What pleases me to no end is to see that collaboration beginning…[for example,] Catholic Charities housing working with Catholic health care.”

Individual counseling has become a key component of complete health care, and not just in terms of wellness and treatment. Many of the people C.H.A. try to serve on the margins are not aware that they qualify for Medicaid or social assistance, or they are intimidated or confused by the health care and social service bureaucracy, a problem that is especially prevalent in the immigrant and refugee communities where Sister Haddad began her career in health care.

Going, as Pope Francis might suggest, to the margins of health service today, she said, indeed means responding to the racial and economic disparities that persist in the United States despite decades of awareness of this problem. But in the end, she said, “there probably isn’t a single person who isn’t on the margins in one way, shape or form…. You could be living on the edge and not know it.”

She explained that as surely as geography, race and income are factors in producing marginalized care, other patients are pressed to the margin because of the nature of the care they need—people seeking assistance from the nation’s poorly resourced mental health system, for example, or families who discover holes in their insurance coverage during a medical crisis or when specialized care is needed. And many others find how close to the margins they have been living when they find themselves unexpectedly out of work and abruptly bereft of health insurance.

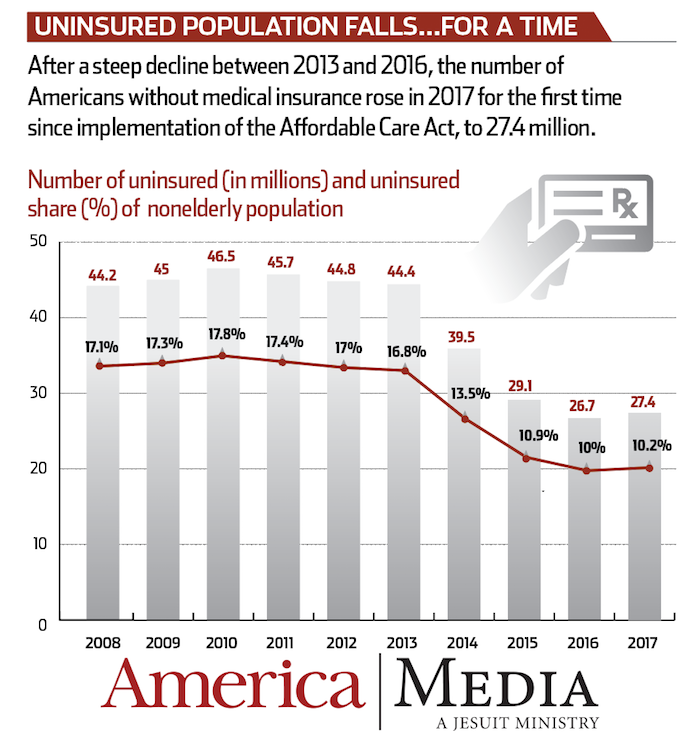

That ongoing effort to broaden health insurance coverage had been an extraordinarily personal fight of her predecessor—Sister Keehan had been credited with saving the Affordable Care Act as it bogged down in Congress in 2010—and it is one she will continue, Sister Haddad said. “We know the importance of Medicaid expansion, but we are in a volatile state just now, given our political situation.”

Sister Haddad said that the C.H.A. under her direction would continue its efforts “to rally advocates and to work with this administration to expand Medicaid and protect and enhance the A.C.A.,” referring to the unfinished work of moving uninsured Americans, now 27.4 million of them, from the margins to the mainstream.

Universal healthcare is a myth we must start with that understanding. Distributing what we can is the objective. Is it the healthcare of 1950? 1980? 2000? 2010? Distributing 2019 to everyone is impossible.

The assertion that “we must start with ” lays down a rule that “Universal health care is a myth” should be regarded as a major premise. In fact, it is a conclusion, your conclusion. The premises from which it is drawn are unstated. A similar observation, of course, could be made about the purported premise that “universal health care is a human right.” Let’s discuss all of this, but let’s do it by climbing the logical staircase one step at a time.

No, it's an observation so it is a premise. Unless you want to consider minimal care as universal health care and no one would accept that. The question is what level of healthcare can be universal?

If you read the rest of what I said, there are various levels of healthcare and the absolute best level is not available to most let alone universal. Then there is what is meant by "universal" which could mean the world or here in the United States. Everything I said was true and logical.

About 25 years ago, I was in a small town in California which had a doctor come once a week. At other times there was a local practical nurse. For emergencies the person had to go 40 miles. Is this what you would call universal health care? In a large part of the country, RN's are the medical staff. So universal health care is a myth is an observation and cannot be achieved.