What are you supposed to do after you have encountered Jesus? Are you to turn away from the culture you grew up in, to immediately leave your nets behind in that way? Are you to hide away so you may cultivate your own relationship with the divine, unadulterated by the occasions of sin rampant in the marketplace? Or are you to convert the society that shaped you and that you have already shaped in so many ways? Are you to act as a leaven in that sinful marketplace?

These are not new questions. But one can sense the ever-newness of the question.

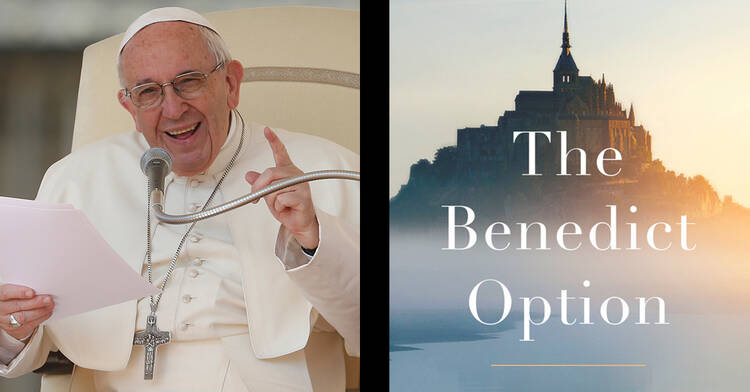

Where the zeitgeist leads next will likely depend on how we answer the questions Rod Dreher raises in his much-discussed bookThe Benedict Option. Its thesis is that Christians hold values and practices that the secular world, stretching across partisan lines and economic classes, no longer can or wants to hear.

Mr. Dreher likens the Christian’s situation in the West to that of Noah’s before the Great Flood. As the author said to the National Press Club, “The flood cannot be turned back. The best we can do is construct arks within which we can ride it out, and by God’s grace make it across the dark sea of time to a future when we do find dry land again, and can start the rebuilding, reseeding and renewal of the earth.” While Mr. Dreher recognizes that getting aboard a modern-day ark must come from a motivation to develop a relationship with God and not simply to hide from a scary secular world, the image and resulting proposal are nonetheless rife with a sense of panic.

Dreher likens the Christian’s situation in the West to that of Noah’s before the Great Flood.

So what does Pope Francis think about the Benedict Option? In truth, he has not explicitly said anything about Mr. Dreher or his book. But my hunch is that Francis is aware of the signs of the times and of the earnest debates that Christians are having.

Some, including Inés San Martín at Crux, suggest that just because Pope Francis may come out with a statement on “bridges not walls,” he is not specifically talking about President Trump or the United States—that our national narcissism often leads to conflating general statements with our own internal debates. But as Cindy Wooden explained here, and Michael O’Loughlin pointed out to me on America’s Jesuitical podcast, “He knows what he’s doing when he kind of needles some of these proposals from the president.” In the same way, Francis may well be aware of the debates about and around The Benedict Option.

My interest was piqued by an address that Francis gave on May 2 to a group of 70,000 members of the Italian lay organization Catholic Action (after I got over the shock that Pope Francis was still working immediately after returning from his historic trip to Egypt). He told them to be missionary disciples, to not look backward but forward with joy, and to channel all initiatives toward evangelization, “not self-conservation.”

Pope Francis told Catholic Action to channel all initiatives toward evangelization, “not self-conservation.”

Speaking about the mission and identity of Catholic Action, Francis told those gathered that they “are essentially, and not occasionally, missionaries.” The pope made it clear that the group at its core needs to go out with the joy of the Gospel. He said they need to be “in prisons, hospitals, the street, villages, factories. If this is not so, it will be an institution of the exclusive that does not say anything to anyone, not even to the church herself.”

This approach from Francis is not new. His first encyclical, “Evangelii Gaudium,” grounds his vision for how the church should relate to the modern world. In fact, Francis thanked Catholic Action for adapting “Evangelii Gaudium” as their own Magna Carta. Pope Francis’ document, like Dreher’s Benedict Option, is critical of the selfish consumerism rampant in modern culture. But “Evangelii Gaudium” offers an entirely different roadmap for engagement with that culture: “[E]vangelization is first and foremost about preaching the Gospel to those who do not know Jesus Christ or who have always rejected him. Many of them are quietly seeking God, led by a yearning to see his face, even in countries of ancient Christian tradition” (No. 15).

Being a Christian in today’s culture is extremely and increasingly difficult. But perhaps it has always been this way, in all cultures, in all vocations.

Francis’ approach is unsurprising given his Jesuit formation. St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, also embraced a world-embracing spirituality. It is no accident that a shorthand for his spirituality is “finding God in all things.” For Ignatius, the world was a place suffused with God’s presence, and every encounter—with a person, a place, even “from the consideration of a little worm,” as one of his biographers once put it—was an opportunity to encounter God. It is no wonder that Ignatius situated the headquarters for the Society of Jesus not in the mountains but smack in the middle of Rome.

Mr. Dreher writes: “We are going to have to change our lives, and our approach to life, in radical ways. In short, we are going to have to be church, without compromise, no matter what it costs.” But as Pope Paul VI wrote in “Evangelii Nuntiandi,” the church “exists in order to evangelize” (No. 14).

One can disagree with Mr. Dreher and still understand his concern. Being a Christian in today’s culture is extremely and increasingly difficult. But perhaps it has always been this way, in all cultures, in all vocations. H. Richard Niebuhr, whose work Christ and Culture is illuminating for debating questions like this, pointed out that there is an underlying assumption in the ideology he terms “Christ against Culture” that sin is found in culture, and the Christian need only to escape culture to escape sin. Niebuhr points to John, who tells us, “If we say, ‘We are without sin,’ we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us” (1 Jn 1:8). If you doubt this, ask any member of a religious community, monastic or mendicant, about the other priests, brothers or sisters with whom they live.

So yes, there may be a degree of risk in engaging a culture that is hostile to you and your tradition. There is a natural fear that you will jeopardize your own faith and its tradition. Nonetheless, we are called to turn away from that fear toward joy. Another quote from “Evangelii Gaudium”:More than by fear of going astray, my hope is that we will be moved by the fear of remaining shut up within structures, which give us a false sense of security, within rules which make us harsh judges, within habits which make us feel safe, while at our door people are starving and Jesus does not tire of saying to us: ‘Give them something to eat’ (No. 49).

Even though Christians may be concerned about their present and future presence in Western society, that is where they are called to be present. And even though there may be an existential risk in engaging a hostile culture, Christians are called to take that risk. Francis told Catholic Action: “To go out means openness, generosity, encounter with the reality beyond the four walls of the institution and the parishes. This means giving up controlling things too much and planning the results.” In that, Christians will find freedom, “which is fruit of the Holy Spirit, which will make you grow.”

Your "Christ Against Culture" example is familiar to Catholics: the religious community. Are you suggesting we abandon religious life to avoid a Benedict Option mindset? (Perhaps we could start with the Jesuits.)

Love your last paragraph.

As a young monk, Thomas Merton wrote pious books for enthusiastic readers. But as time went on he realized that he could no longer be a guilty bystander. He started writing controversial books about injustice, discrimination, racial violence, the evils of capitalism and the exploitation of poor countries by rich countries. He condemned the Vietnam war and any war.

Merton's message was clear: Turn toward the world and engage with it as it is. Very similar to Francis' insight to "encounter with the reality beyond the four walls of the institution and the parishes."

Hi Zac,

I'm still unsure what you think Pope Francis may think of the Benedict Option per se. As a big fan of Dreher's concept, I want to point out that the Benedict Option was named for the man who literally saved Western civilization through institutionalizing Christianity. Could somebody living at the time incorrectly seen it as "merely" a fortress mentality? Sure. But they would have been proven wrong as the fruit of St. Benedict's efforts have been obvious. From this seed bed came all religious orders. And then came the fruit of those orders: hospitals, schools and universities, poor houses, radio stations, tv stations, and Catholic magazines (such as America). Even the diocesan priesthood can trace its roots back to this "original" Benedict Option.

So, I don't think the Benedict Option is at odds with the New Evangelization. It's my view that it will greatly enhance our Church's evangelization efforts, as tight-knit parish communities, homeschooling parents, and unabashedly Catholic universities give way to proper and permanent evangelization in the form of future vineyard workers for these institutions (and even those yet to be dreamed).

Bless you for all your work at America. I don't suppose this will be the final time you'll address the Benedict Option concept. I look forward to reading more.

Dominic Deus here: Michael O'Connor, thank you for your post. This strikes me as a discussion worth having. My concern with Dreher is that he seems to be proposing some kind of initial withdrawal from engagement with the world followed by small group self-purification leading to a return to the world with a perfected message of evangelistic fervor.

I find people like that a little scary.

For one thing, neither their idea nor their ideologies are anything new. Their most recent iteration in the "born again," judgementalist, evangelical exclusivist Christians has been so divisive that it has given traditional evangelism a bad name or at least guilt by association.

Perhaps that is not Dreher. Maybe there is more to him. Perhaps his message is more authentic.

In response to your analysis, I think your encapsulation of the Benedictine legacy is quite correct and I celebrate it, but is that what Dreher is proposing? I don't think the world needs the re-incarnation of Benedict or his works. It needs the incarnation of what the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, our brother, the carpenter, the builder, the teacher and story teller can do for the world we live in now.

--Dominic

Hi Dominic,

I should begin by pointing out that the "born again" crowd is perhaps the polar opposite of what Dreher is recommending. Evangelical Christians do not send their children to Christian schools, (their megachurches don't start schools as they believe focus should remain on worship). They accept divorce and contraception, they don't adhere to the corporal works of mercy (no hospitals), and they are under no obligation to attend church on Sundays. If anything, these Christians who are most engaged with the culture, look the least like traditional Christians. And I think that is not coincidental.

I'm sorry if you find some Christians scary. But is it justified to say that any Christian who thinks differently than me is scary? Are they scarier than the Atheist Peter Singer who advocates for the Orwellian "post-birth abortion" or the Dutch government that has now made euthanasia optional for sick people? My point being, despite major theological differences, I think we have more in common with the Mormons, Evangelical Protestants, Amish mennonites, and Jehovah's Witnesses than with the secularists in the wider society.

And to your final point, we'll just have to agree to disagree. Sixteen popes have taken Benedict's name because they believed he was perhaps the best model of Catholic virtue. I agree with them. His ability to "think big" is virtually unparalleled (there are lots of great saints, and we could endlessly debate who's the "best"). There will never be another "incarnation of Jesus" until the Last Day, but another Benedict gives all of us a very practical (though difficult) road map for the future.

Happy Sunday,

Michael

I am bothered that I read well more than half the article before I encountered a comment about helping the poor, and that a very short one, not expanded on much.

Evangelizing is worthless if you do not know what to preach. All the confusion and doubt about confronting society is nonsense, if your only fear is for yourself.

Instead, focus on working for others, raising the poor and feeding the hungry, which Jesus made absolutely clear is his greatest challenge to us.

If you challenge on behalf of others you have much less to fear from calling out society.