Bite-Sized Bible: Digesting God's Word in '140 Characters or Less'

A mere thousand years ago, lay Christians didn’t read the Bible at all, not least because it was not widely available in their language, or indeed available at all. Even the monks with access to the Scriptures—some of them already busy translating sections into Slavic or Old English—couldn’t cite them chapter and verse, because those helpful chapter breaks would not be inserted until the 13th century, with the verses to come in the 16th.

Now that we’re nearly in a post-print age—a time when more words are being composed and read than ever before, but not necessarily on paper, or in long form, or even in standard English—whither the Good Book? Now more easily digestible, with not only organizing numbers but concordances, annotations and study guides galore, the sacred texts of the Jewish and Christian traditions haven’t just been sprung from the ark and liberated from the parchment. They are now so much digital flotsam, sloshing around in the Wi-Fi cloud along with our Facebook feeds, Netflix queues, Kindle purchases and other things the NSA seems to find so interesting. This jostling with the profane is nothing new—after all, Bibles have sat on bookshelves next to cookbooks and bodice rippers, rested discreetly in millions of hotel room drawers, without any lasting damage to their holiness. But in the decoupling of the written word and page, and more broadly in the divorce of rich, deeply acculturated texts from their larger context, it’s fair to wonder if we may be losing something of value in our relationship to the Scriptures, let alone Christian communion. For one thing, the temptation to cherry-pick quotations, already an inevitable consequence of the Bible’s wide availability, has a seductive handmaiden in the age of Twitter.

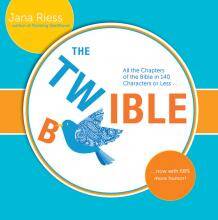

Of this queasy new meta-information age, Jana Riess’ ambitious new compendium The Twible is both a symptom and a sneaky corrective. It’s the fruit of a years-long project by Riess, a blogger for Religion News Service, in which she set herself the task of reading all 1,189 chapters of the Bible and composing a tart tweet about each one. The result, in handy self-published paperback form, is a kind of shotgun marriage between one of those ubiquitous “Idiot’s Guides” (Riess co-wrote Mormonism for Dummies) and a high-concept spiritual-stunt book, like A.J. Jacobs’ The Year of Living Biblically or David Plotz’s Good Book (based on his “Blogging the Bible” series for Slate). Riess made her own fine and searching contribution to this field with 2011’s Flunking Sainthood, in which she spent a year trying out revered spiritual practices, one at a time, and recording her struggles with each in a bracingly frank and often funny voice.

The Twible, too, shows off Riess’ sharp eye, admirable directness and deep but lightly worn knowledge of matters both theological and textual. The page-long commentaries that are peppered among the chapter-by-chapter tweets are especially well-turned mini-essays on scriptural history and interpretation (with a few fun lists thrown in, such as “10 Biblical Names That Shouldn’t Be Used Again Anytime Soon” or “Five Deuteronomic Laws We Really Hope You’re Not Observing”).

These sidebars stand out for another reason: They are blessedly liberated from the 140-character straitjacket the Twitter format imposes on the bulk of The Twible’s text. On an Internet browser or a phone app, good tweets can offer delightful bursts of pith and vinegar; it’s an ideal medium for both aphorisms and one-liners. And it’s very easy to imagine how the task Riess set for herself—to say something relevant, informed and funny about each chapter she comes across—might have played well, as she doled out tweets to her delighted Twitter followers over weeks and months. But printed together, on pages that don’t actually have such bandwidth constraints, the form has a herky-jerky rhythm that takes some getting used to. A typical tweet, on 1 Kings 18: “Theology throwdown; Elij dares 850 pagan prophets to duel. Elij: ‘Ha! Is that all you’ve got? LMAO @ your girly-man gods.’” Not every tweet is clogged with online abbreviations, but the pop-culture references—to reality television, Disney animated films, Game of Thrones, etc.—have a destined-to-be-dated feel to them that’s at odds with the book’s timeless themes.

Not that Riess can’t pull off a neat rimshot now and then. On 2 Kings 1: “King has nasty fall and goes to Baal Hospital for consult. Out of network! G’s own Dr. Elijah puts king on bed rest...FOREVER.” She dispatches one of the New Testament’s greatest hits with perfect pitch, saying of 1 Corinthians 13, “Love is patient and kind. It does not get annoyed or impatient that this chapter is read at Every. Single. Wedding. Love bears all.” And though she doesn’t have room to note Philippians 2’s ancient origins—some scholars believe it’s a remnant of the first Christian hymn, predating any written Gospel—she serves up this neat editorial zinger: “Paul insists that church must always have unity in everything. Thousands of different Christian denominations now agree.”

In case you haven’t already guessed, Riess has not written a reverent or devotional scriptural guide. A practicing Mormon with a Masters in theology from Princeton Theological Seminary, Riess has a matter-of-factly feminist, modernist reading of the Bible’s more terrifyingly violent and misogynist passages, from the bloody contention between Judah and Israel to the pornographic ravings of Ezekiel. Indeed, this unflinching approach, wed to her often snarky tone, might give a casual reader the impression that Riess is a secular scoffer. And certainly not every believer is going to be amused by her often flippant take on some especially harrowing passages (blessedly, she takes a pass on joking about the crucifixion).

But in her illuminating commentaries on the Psalms, she offers what might be her book’s mission statement: “Real faith involves serious questions and doubts, and is not satisfied by platitudes. There’s a world of suffering in these pages, as well as hope and praise.” In a related commentary, on the Wisdom books, she gives the game away in recommending a look back at the original text: “The poetry is often gorgeous, and 140 characters can’t even begin to do it justice.” Ya think?

That dissonance is a hint to why The Twible, though not a filling meal on its own right, may best be seen as a kind of “Mystery Science Theater 3000”-style companion to the original. Indeed, the best thing about Riess’ project is that, paradoxically, by stacking these little word-blasts together and framing them with some helpful commentary, she manages to give a lively sense of the books and traditions from which they spring. If The Twible sends readers back, refreshed, to experience the fullness and breadth of the Good Book anew, so much the better.