In recent months, a certain slice of conservative media has been busy stirring up outrage over critical race theory. Not surprisingly, many of these attacks show little or no awareness of the content of critical race theory and the questions that C.R.T. raises. Nor do the attackers seem to know that C.R.T. is not part of most grade school and high school curricula, and is discussed in only a very few college courses. In this environment of stirred-up outrage, some white people claim that they are victims. These attacks make it even harder to have an honest discussion about race in America. To understand racism today, one must understand the history of slavery, Jim Crow, segregation and discrimination and see the lingering effects that haunt our nation, both in the attitudes of many and in the systemic inequalities found in the criminal justice system, policing, housing, education and health care.

Many white readers were shocked to hear the details in Black Like Me. But African-Americans did not need his book; they knew what was going on.

This honest discussion of race for many whites is long overdue. Some had hoped it would come after the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Mo., or with Colin Kaepernick taking a knee in 2016, or with nine minutes of George Floyd suffocating in 2020. The manufactured outrage over C.R.T. makes it seem even more unlikely to happen.

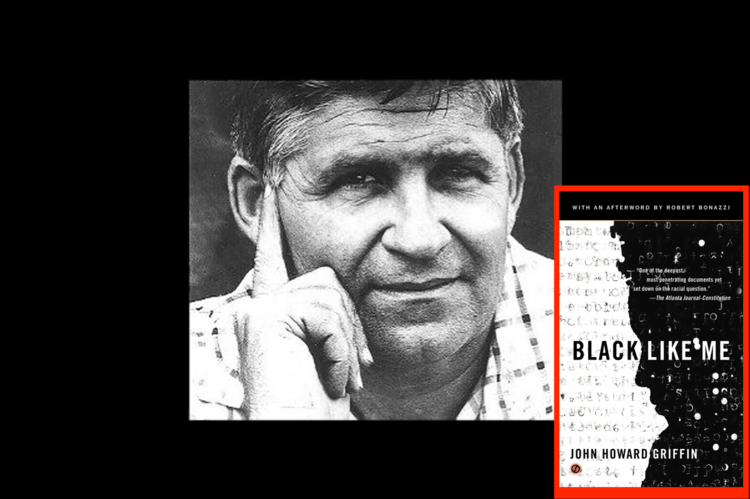

Sixty years ago, in 1961, John Howard Griffin (1920-1980) published Black Like Me to create awareness among whites of how African-Americans were treated in the South under Jim Crow, the system of laws and customs that took away most rights, privileges and freedoms from African-Americans and treated them as second-class citizens. Although Jim Crow first evolved in the Southern states, African-Americans in the Northern states experienced similar discrimination. Many white readers were shocked to hear the details in Griffin’s popular book. Many could not believe that in good and decent America, such things actually took place. But African-Americans did not need his book; they knew what was going on.

Griffin’s life

Born in 1920, John Howard Griffin grew up in Dallas, Tex., and he learned to love music from his classical pianist mother. As a young man, he studied in France, developing a deep interest in Gregorian chant and monasticism. In the late 1930s, he helped Jews escape France. He spent three years during the Second World War in the South Pacific in the Army Air Corps; he was injured by an exploding shell and lost most of his sight.

Returning to the United States, he eventually became completely blind. In time he married and had four children. He converted to Catholicism in 1952 and became friends with Catholic figures such as the philosopher Jacques Maritain and the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. The same year as his conversion, Griffin published his first novel, The Devil Rides Outside. He would eventually produce a dozen books.

After 10 years of blindness, his sight returned. With recovery of his sight, he resumed his interest in photography.

The Church and the Black Man lays out issues around race and the Catholic Church that are still playing out today.

In 1969, Griffin published The Church and the Black Man, a short book giving his candid look at the Catholic response to racism in America. Some Catholics were rankled by its honesty. For example, he describes how Catholic sisters who participated in the 1965 Selma march for voting rights were accused of being prostitutes, and how priests who stood up for racial justice were often harassed or had their reputations ruined.

The Church and the Black Man is still worth reading today, for it lays out issues around race and the Catholic Church that are still playing out today. How many parishes in suburban areas were built in response to white flight from inner cities? Are there parishes today where priests fear bringing up the subject of Catholic teaching on race and racism?

After Thomas Merton died in 1968, Griffin was appointed to be his official biographer. However, Griffin’s ill health prevented the completion of this project. He nearly completed a book on Merton’s later years, posthumously published as Follow the Ecstasy: Thomas Merton, The Hermitage Years, 1965-1968.

John Howard Griffin died in 1980 due to complications from diabetes (not, as was rumored, from the effects of changing his skin color). Robert Bonazzi wrote a biography, Reluctant Activist: The Authorized Biography of John Howard Griffin, that describes Griffin’s life and his spiritual journey with long quotes from his journals.

Griffin caught racists in their lie: It was all about color.

The experiment

Griffin’s Black Like Me reads like a series of journal entries describing a six-week period when, using medication, ultraviolet light treatments and sponged-on stain, he turned his skin black. He then went out in public in New Orleans and Mississippi and saw that everything for him had changed.

His message is told in his reflections on what he sees and experiences and by the words of African-Americans who speak candidly to him. As for the racist whites in their conversations with Griffin, they damn themselves. Particularly noteworthy is the book’s descriptions of the intense pressure on moderate whites to go along with a racist system and racist attitudes.

Admittedly, not that much happens during this experience; he is not attacked or beaten up. But his details are enough to give a window into the world of Jim Crow segregation. Griffin, as well as others such as James Baldwin, tried to explore the question of why so many white Americans had and have an unhealthy need to keep racism alive. And one can feel a certain frustration reading Griffin, for although much has changed since 1961, many white people still hold very ignorant and racist attitudes.

Griffin’s book was turned into the 1964 movie “Black Like Me,” starring James Whitmore. Meyer Kupferman wrote a powerful and edgy music score for the film. (The movie can be found on YouTube.) The DVD version includes the documentary “Uncommon Vision: The Life and Times of John Howard Griffin.”

Griffin admitted he was running an experiment. The claim of the racist is that discriminatory treatment based on race is not about skin color, but about some fundamental difference of character. Griffin caught racists in their lie: It was all about color. Nothing had changed about him except his color, but when that changed, most whites treated him very differently. Once his color changed he could not even eat at his favorite New Orleans restaurant. After several weeks, he stopped taking the medicine and staining himself; his skin returned to its normal color, and then he could enter the restaurant.

Griffin was not the only white writer to conduct the same experiment. Ray Sprigle described his experience in his 1949 book In the Land of Jim Crow. Grace Halsell wrote about her experiences in Soul Sister: The Story of a White Woman Who Turned Herself Black and Went to Live and Work in Harlem and Mississippi. (Halsell spoke to Griffin before her travels to Harlem.)

Readers taking up Black Like Me for the first time may find it stirring in its simplicity.

The epilogue

In later editions of Black Like Me, Griffin added an insightful epilogue that shows how intractable the problem of racism was in white society in the United States. Griffin discovered that many people read his book and were willing to listen to him speak, yet seemed unwilling to read African-American authors or hear them speak. He describes how he would travel with the African-American comedian and activist Dick Gregory to speak to crowds. They agreed to make the same points in their talks. Griffin received warm responses with much applause, while Gregory, saying the same things, was met with hostility.

Griffin also described how cities and towns would invite him to give his thoughts on racial problems in their communities yet ignore the African-American leaders. The white leaders were not listening to the local Black leaders, yet they wanted the thoughts of Griffin.

The legacy

Today, some might question the wisdom and legitimacy of a white man trying to show the African-American experience. How could he truly understand it? And why can’t people just read African-American authors? But one must keep in mind that although there are many media outlets today where one can find a diverse range of voices of African-Americans speaking about their own experiences, this was not always the case. Sixty years ago, very few such outlets existed.

Readers taking up this modestly sized book for the first time may find it stirring in its simplicity. Such readers would then do well to read Griffin’s follow-up book, The Church and the Black Man. And then, of course: Start reading James Baldwin.

Many of the people who most need to hear the ideas in these books are not interested. Many Americans are being encouraged to retreat further into their fear, outrage and ignorance. And most tragically, as we remember the 60th anniversary of the publication of Black Like Me, we may have to face the reality that we will still be dealing with these issues some 60 years from now.