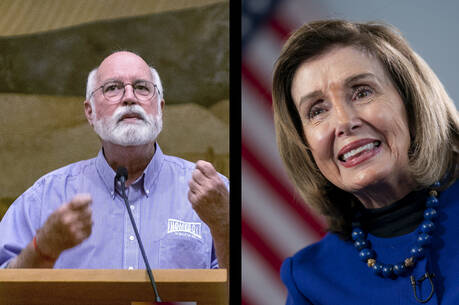

In Episode 2 of “Hark!,” America Media’s new podcast about the origins of our favorite Christmas carols, host Maggi Van Dorn digs into “O Come, O Come Emmanuel” with Cameron Upchurch, the organist at St. John’s College in Johannesburg, South Africa, and the Jesuit composer and founding member of the St. Louis Jesuits, Robert “Roc” O’Connor, S.J.

Early on, Mr. Upchurch talks about how his students love “Emmanuel” because the sound of it is so much more mysterious than other carols. One of our editors, Molly Cahill, described it as “eerie.”

That is not generally a quality we ascribe to Christmas carols. We are talking about the birth of our Savior here, not the set up for an Edgar Allan Poe story. But “Emmanuel” has an undeniably spooky quality to it. Sometimes that has to do with the opening, as in this 2016 performance by the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge. Something about that organ transports you back to a chill, moonless night on the moors of Victorian England.

That is not generally a quality we ascribe to Christmas carols. We are talking about the birth of our Savior here, not the set up for an Edgar Allan Poe story.

But a lot of it is also in the pacing. Where many Christmas carols have either an upbeat tempo (like the carol featured on Episode 3 of the podcast, “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”) or a lush, contemplative vibe (like “Silent Night,” whose hushed tones makes you feel like you are right there in the manger with the Holy Family), “Emmanuel” usually has a quiet, persistent speed that signals something is coming, without giving us any clear sense of what.

As odd as it sounds, though, that uncertain quality is actually quite fitting. Unlike other popular carols, “Emmanuel” is a song not for Christmas but for Advent. And in the Scripture readings during Advent, we watch all kinds of different characters receiving portents and predictions about Jesus. Some take them well. Others do not. In the Gospel of Matthew, King Herod is so frightened at what the coming of a messiah might mean that he has all boys under the age of 2 in the Bethlehem area massacred.

As odd as it sounds, though, that uncertain quality is actually quite fitting. Unlike other popular carols, “Emmanuel” is a song not for Christmas but for Advent.

But no one, not Jesus’ family or friends, enemies or future disciples, or even Jesus himself by some accounts, will fully understand what he is until after his death and resurrection. He is not at all what anyone expected.

Two thousand and some years later, we have a much clearer sense of who Jesus is, but that also means we know just how impossible he is to anticipate. So it makes sense that we, too, might be a little uneasy. We know what we hope for, but will that be who shows up?

Roc O’Connor puts it well: “It’s so difficult to be vulnerable before God, to meet myself as vulnerable and be vulnerable with anybody else.” And yet in Advent, that is what we try to do, to surrender ourselves to the waiting and trust that God will respond with the love he promises.

Check out this episode for many more great insights into “O Come, O Come Emmanuel,” including how it became the carol we know and love—as well as O’Connor’s ideas on how to play the song at Mass.

Listen to all episodes of Hark! here: