In the 1960s, there were places in California where people of Mexican origin could not use the swimming pool. I never learned that history while growing up in California in the early 2000s. It is not the kind of education one receives in California public schools, where Latinos make up a majority of the student population yet continue to be failed by California’s education system by nearly every measure.

This selective teaching of history represents epistemological violence, which is defined as an assault on the collective memory of a people. Because of this, I could never put the small but daily racial humiliations of my childhood and teenage years as a Mexican-American into their proper historical context: The land of my childhood had once been Mexico to begin with. And when I was angry about what had been done to me, I did not have an example of resistance.

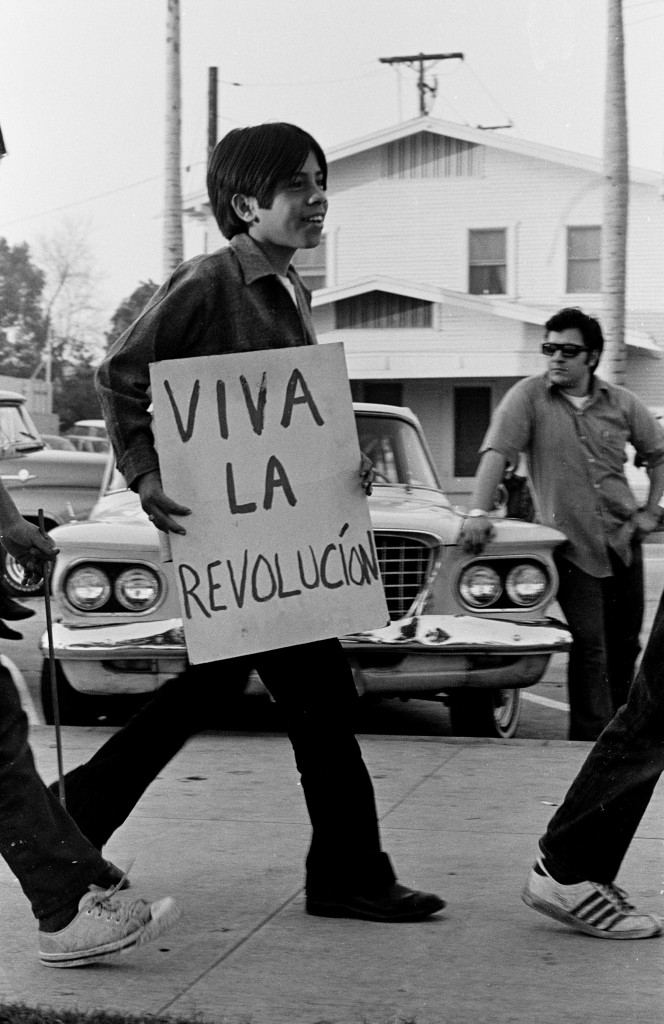

For young Chicanos like me looking for ways to define our identity or for examples of resistance in the age of Trump, the pictures at the Raza exhibit are postcards from the past, reminding us we have been through worse.

But that example was there. The history of Chicano resistance, struggle and survival in the United States is epic and inspiring. Just the word “Chicano” moves me. It is the one term for ourselves that we chose; once derogatory, meaning literally “the little people,” it was reclaimed by Mexican-American youth in the mid-20th century as a way of signaling pride and defiance. The term will forever be associated with the eponymous movement of the 1960s and ’70s. This movement was largely a youth movement, born in California’s substandard schools in parallel to the ongoing farmworkers movement and the broader civil rights and anti-war movements. What tied these struggles—urban and rural, students and farmworkers—was a shared sense of identity and a newfound pride. “Chicano” represented the self-articulation of a people.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of many historic moments of the Chicano movement, a new photography exhibit is telling the Chicano story through the eyes of its participants. The “La Raza” exhibit at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles is a unique collection of over 200 rare photography prints, mostly taken by citizen-journalists of the activist newspaper “La Raza” over the course of a decade.

Historic moments like the Chicano Moratorium, one of the largest single protests against the Vietnam War, are well represented. On Aug. 29, 1970, tens of thousands of mostly working-class Mexican-Americans of all ages marched through East Los Angeles, drawing attention to the disproportionately high casualty rates of Chicanos in Vietnam. The day turned violent when police attacked the rally, leading to the death of Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Salazar, who was shot in the head at close range by a tear gas canister fired by a Los Angeles Sheriff’s deputy. Also captured on film are the daily difficulties and joys of Chicano life in a time of upheaval: children playing on barrio streets, old men hiding from the sun in the shade of Central Valley trees; teenagers flirting and gossiping on their way home from Chicano movement marches.

There is no better place for the Raza exhibit than the Autry. Named for Gene Autry, the singer, actor, rodeo star and businessman who did so much to define the myth of the Wild West in his own lifetime, much of the museum now acknowledges the often brutal realities of how the West was won or, in the case of Chicanos, lost. As you move from the Raza exhibit to other parts of the Autry, you see the guns, the revolvers, all the elements of the romanticized Western and the tools by which a violent and racially fueled conquest was carried out.

This is the context in which Chicano history belongs. Mexican-American history is uniquely Western history, just as Western culture, from the cowboy to pulled pork to the rodeo, is essentially Mexican culture, stolen and bent to Anglo convenience along with the land itself. Today, we think of the marginalization of Latinos chiefly in terms of immigration. The Chicano movement articulated many of the other concerns Latinos have faced, from the racial achievement gap to fair labor practices for farmworkers, injustices that persist to this day.

This history sheds a special light on the exhibit’s rare photography of “La Marcha de Reconquista,” an event that I had never heard of despite completing a bachelor’s degree in Chicana/o studies. Organized by the Brown Berets, the “march of reconquest” began on May 5, 1971, the anniversary of the Battle of Puebla, where Mexican forces defeated an invading French army. The Cinco de Mayo march began at the Mexican border in Calexico and over the period of three months, activists, farmworkers, students and families walked to Sacramento. On the way, they passed through the Coachella Valley, the barrios of Los Angeles and the Central Valley—all places where then, as now, there are strong Latino communities battling against entrenched racial and economic divides. The march seemed to remind everyone: This was all once ours. And it could be again.

For young Chicanos like me looking for ways to define our identity or for examples of resistance in the age of Trump, the pictures at the Raza exhibit are postcards from the past, reminding us we have been through worse. The names and faces of the Chicanos in the photographs are not quite my ancestors; my Bracero grandfather returned to Mexico before the Chicano movement began, while my parents came to this country in the late ’80s. But they are my ancestors in a way—my life’s opportunities have been built upon the foundations they set, and I am the proud inheritor of their struggles.

If you want a complete history of the Wild West that stretches from myth into reality and from the past to the present, then consider a trip to the Autry. “La Raza” is well worth your time as a window into the lives of a people who are very much still contesting the results of history.

Too young to remember that Cesar Chavez, the man who organized the UFW in 1962, fought against illegal immigration. He believed it depressed the wages of farm workers.

...and please, editors, no epistemological eponymous Greek where plain English will do.

“Resistance” is a term for anarchists, as should be obvious from the violent partisans of our day like Antifa. It’s a term never used by MLK. The US Constitutional government is not inherently repressive or racist, despite the people who run it. MLK appealed to majority America’s Christian and historic sensibility that it fulfill “all men are created equal,” and majority America responded. While understandable in a secular publication, this article’s un-Christian combativeness is depressingly out of place here.

Antifa? American Nazis are marching down the street with torches, shooting at people and driving cars into non-nazis. I disagree with antifa mostly because they allow "conservatives" to huff and puff and apply their double standard.