As Catholic students and others traveled to Washington, D.C., for the March for Life, the U.S. Supreme Court was scheduled to hear oral arguments for Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, a case that could have major implications for the future of Catholic schools. The question is whether the court will take the opportunity to strike down Blaine Amendments, which bar government funds from going to religious schools in 37 states and were largely enacted during a wave of anti-Catholicism in the late 19th century.

At issue is a program in Montana (similar to programs in 18 other states) that provides tax credits to those who donate to nonprofit organizations that, in turn, grant scholarships that families can use at private schools, including religious ones. Montana’s highest court ruled that the program violated the state constitution’s ban on government support, direct or indirect, for religious institutions. The Institute for Justice, representing three Montana families, is arguing that by throwing out the program, the state of Montana violated the right to religious freedom guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

At issue is a program in Montana that provides tax credits to those who donate to nonprofit organizations that, in turn, grant scholarships that families can use at religious schools.

It is important to note that the Montana program did not involve vouchers. Voucher programs, enacted in 12 states in addition to Puerto Rico and Washington D.C., provide families with state grants that can be used for tuition at any private school, including religious schools. The Montana program is instead similar to a tax-credit scholarship program in Arizona, which also has a Blaine Amendment in its constitution (though that state’s Supreme Court has interpreted the amendment more narrowly and has not invalidated the tax-credit program).

The Arizona program was essentially upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Arizona v. Winn in 2011 because the plaintiff in the case, a state taxpayer, had no grounds to sue. A 5-4 majority denied standing to the plaintiff, in part, because tax credits are not governmental expenditures: “Objecting taxpayers know that their fellow citizens, not the State, decide to contribute and in fact make the contribution.... Like contributions that lead to charitable tax deductions, contributions yielding [school tuition organization] tax credits are not owed to the State and, in fact, pass directly from taxpayers to private organizations.” (The opinion was written by Anthony Kennedy, and the majority also included John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito; the dissenters were Elena Kagan, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer and Sonia Sotomayor.)

The critical distinction between state money distributed as vouchers and tax-credit scholarship programs was made clear in the oral arguments for that case. Justice Scalia stated: “That’s a great leap to say that it’s government funds, that any money the government doesn’t take from me, because it gives me a deduction, is government money…. This money has never been in the government’s coffers.”

In a 2011 case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that tax credits are not government expenditures.

Justice Kennedy added: “If you reach a certain age, you can get a card and go to certain restaurants, and they will give you 10 percent credit. I think it would be rather offensive for the cashier to say, ‘And be careful how you spend my money.’” This line of questioning generated laughter in the courtroom.

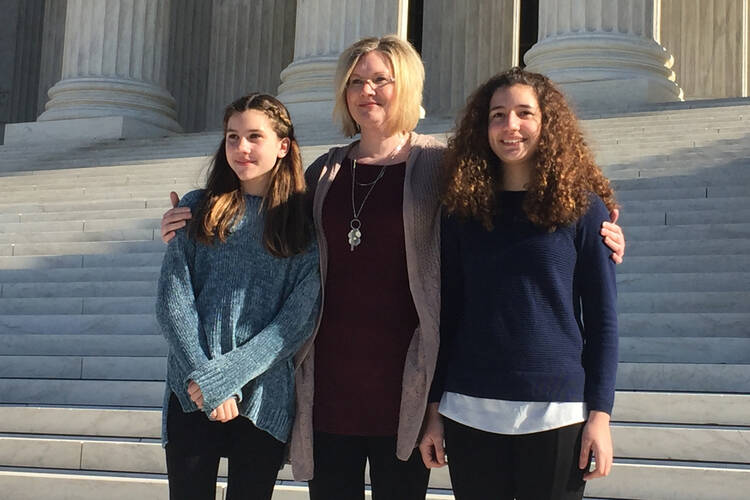

Despite this ruling, the rationale used by the lower courts to deny Kendra Espinoza, a low-income mother of two who holds two jobs as a janitor and an office assistant, from receiving a scholarship for her two daughters to attend a religious school was Montana’s Blaine Amendment. Blaine Amendments take their name from Senator James Blaine, the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives who in 1875 introduced a federal constitutional amendment to prohibit funding “raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools” from ever being “under the control of any religious sect.” At a time when large numbers of Catholic immigrants were arriving in the United States, the amendment won overwhelming approval in the House but failed in the Senate by four votes. Nevertheless, it made its way into the state constitutions of 37 states.

Blaine Amendments have been cited by state courts to strike down all manner of student-aid initiatives.

So far the Supreme Court has declined to directly address the question of whether Blaine Amendments are compatible with the U.S. Constitution. But in Mitchell v. Helms (2000), a 6-3 majority ruled that Jefferson Parish, in Louisiana, did not run afoul of the First Amendment in distributing federal funds to religious and other private schools for the purchase of computer equipment and the implementation of “secular, neutral, and non-ideological programs.” In the plurality opinion, Justice Thomas stated that “hostility to aid to pervasively sectarian schools has a shameful pedigree that we do not hesitate to disavow.... Consideration of the [Blaine] amendment arose at a time of pervasive hostility to the Catholic Church and to Catholics in general, and it was an open secret that ‘sectarian’ was code for ‘Catholic’.... [B]orn of bigotry, [Blaine Amendments] should be buried now.”

Blaine Amendments have been cited by state courts to strike down all manner of student-aid initiatives. But as the final paragraphs of the appeal in the Espinoza case state, “all children suffer when these court decisions discourage legislatures from enacting new student-aid programs. Every session, dozens of state legislatures consider bills that would give families greater educational choice, whether in the form of tuition scholarships, private educational savings accounts, textbook loan programs, or transportation subsidies. But…legislators are understandably reluctant to pass a bill if it will only be later invalidated for including religious schools.” (Indeed, legislators in four states that have Blaine Amendments—Idaho, Kentucky, Missouri and New Hampshire—have expressed concerns about passing student-aid programs because of their states’ Blaine Amendments. This cloud of uncertainty has prevented these states from passing new programs over the last two legislative sessions.)

More recently, in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer (2017), the Supreme Court in a 7-2 decision chose not to invalidate Missouri’s Blaine Amendment but nevertheless held that the Missouri Department of Natural Resources erred in not allowing a religious preschool from participating in a state program that provides funds for resurfacing playgrounds.

Given that ruling and the past opinions of current justices, it seems unlikely that the Supreme Court will agree with the Montana Supreme Court that religious schools must be excluded from the state’s tax-credit program. But it is possible that Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue will be decided so narrowly as to not even mention Blaine Amendments, instead echoing the Arizona v. Winn ruling that tax credits do not meet the definition of state funding.

While such a decision would be beneficial to families in Montana, it would miss a tremendous opportunity to finally bury Blaine Amendments for families once and for all. Such a move would enable legislatures to craft tax-credit scholarship programs and possibly voucher programs that enable children like Kendra Espinoza to receive scholarships that make the choice of a Catholic school—or for that matter any private school—a realistic option.