This article is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

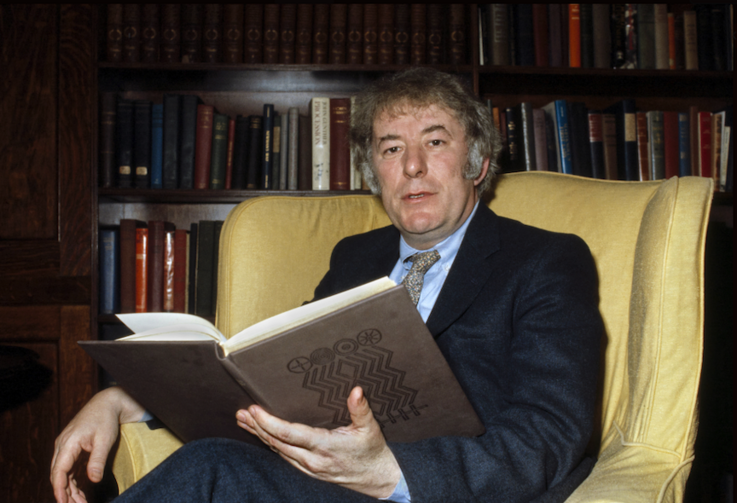

There will soon be a huge volume of collected Poems of Seamus Heaney (1,100 pages), to go with the hardback and paperback versions of The Letters of Seamus Heaney (884 pages). These two tomes give a subtle and multi-hued portrait of a life often lived in the public eye, as Heaney pursued a late-20th-century vocation as a public advocate of poetry and as a somewhat private advocate of Catholicism as a folk culture, if not a political one.

Heaney’s letters give two spiritual accounts of himself, one to the English poet laureate Ted Hughes on the occasion of a visit to a Mass in Spain in 1996, where “the whole underlife of my childhood and teens rallied and wept for itself…it was potent because there is just enough ‘living faith’ about the place to make you feel the huge collapse that has taken place at the centre of the Christian thing.” Ten years later, he responded to an essay on aging by Jane Miller with an acknowledgment that his rural Catholic upbringing in County Derry provided “a structured reading of the mortal condition that I’ve never quite deconstructed.” He continued:

Naturally I went on to school myself as best I could from catechised youth into secular adult. The study of literature, the discovery of wine, women and song, the arrival of poetry, then marriage and family, plus a general, generational assent to the proposition that God is dead, all that cloaked and draped out the first visionary world.

Indeed, one could read Heaney’s poetic oeuvre as that of the bard who describes the retreat from faith, the tide of Christianity washing out of his native Ireland. Yet between those two tomes is the recently published Translations of Seamus Heaney (685 pages), which shows that even as he gave one account of himself in poetry and a parallel private one in his letters, there was a third hidden spiritual life being conducted in his professionally commissioned and occasional translations. This private spiritual life hidden in plain sight is brought into focus in this volume, lovingly edited by one of his last collaborators, Marco Sonzogni.

The third piece in the book, from Heaney’s most political book, North, of 1973, is a translation of Baudelaire, “The Digging Skeleton”:

This is the reward of faith

In rest eternal. Even death

Lies. The void deceives.

We do not fall like autumn leaves

To sleep in peace. Some traitor breath

Revives our clay, sends us abroad

And by the sweat of our stripped brows

We earn our deaths: our one repose

When the bleeding instep finds its spade.

Gary Wade argues in Seamus Heaney and Catholicism that Heaney’s childhood Catholicism on the family farm, Mossbawn, was a folk version that predated the clerical revamp of the modern church, a form of Marian cult that Heaney clearly associated with his primary relationship with his mother. The Irish public voted his poem that begins “While all the others were away at Mass” about peeling potatoes with his mother as their favorite poem ever; while it may seem a secular poem, it is also one that sacralizes his relationship with his mother.

Wade also notes that much of Heaney’s erotic poetry conjures the charge of touching the beloved’s female anatomy in faintly blasphemous terms by comparing, for instance, his wife’s “black plunge-line night dress” to the “priest’s chasuble/ At a funeral mass,” or, in “La Toilette,” “the first coldness” of his wife’s breast “like a ciborium in the palm.”

Heaney also wrote many poems valorizing his father’s manual labor about the farm but also using “digging” with a pen as a parallel metaphor for his own labor. If one viewed Heaney’s poetic career as a long tribute to his love for his mother (religion) and his father (rural labor) then his translations were always examining the foundations of that edifice, like a civic engineer testing the pipes.

I first encountered Heaney’s translation work with his single most famous work, the translation of “Beowulf” that was considered so culturally significant as to win that year’s Whitbread Prize, for which works of translation are not usually submitted. I confess I found it unsatisfying. Not as a representation of Old English, which I’ve no tools to judge with, but as a representation of life. I first encountered Heaney at a poetry reading in 1986 where he read a section of his “Station Island” describing William Streathearn, a pharmacist murdered by two Royal Constabulary officers in 1977:

His brow

Was blown open above the eye and blood

Had dried on his neck and cheek.

I had not read “Station Island,” only heard it that once from him, but such was the force of the horror in the lines that I remembered it 13 years later and found nothing to equal it in the descriptions of gore in Heaney’s “Beowulf”:

He grabbed and mauled a man on his bench

Bit into his bone-lappings, bolted down his blood

And gorged on him in blood, leaving the body

Utterly lifeless, eaten up….

What I missed in my visceral reading, which I still consider sound, was the bigger picture of what Heaney was doing, where and when. The original manuscript of “Beowulf” dates from 975 A.D., a mere thousand years into Christianity, and it is a matter of dispute whether it was composed much earlier in pagan times or by a Christian. Either way, what this collection makes clear by arranging all Heaney’s occasional poetry translation around this central work, is that it is one thing altogether to write of the grace of God when Christianity is taking hold of a culture and quite another when it is washing out. A millennium later Heaney is perhaps the only English poet who could have infused such lines as this with full bodied conviction in 1999, writing of the Geats who turn to their pagan idols in distress:

Oh cursed is he

Who in times of trouble has to thrust his soul

In the fire’s embrace, forfeiting help;

He has nowhere to turn. But blessed is he

Who after death can approach the Lord

And find friendship in the Father’s embrace.

I found the best encapsulation of Heaney’s ultimately elusive cultural, theological and linguistic role in 20th-century culture in Sonzogni’s notes to the translation of “Caedmon’s Hymn” (c. 657-84). Caedmon was a cowherd who joined a monastery, and as the critic Holsinger points out, his song’s “diverse appearance in Latin and Old English texts of Bede (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) leaves its critics unsettled on the basic question of whether what now survives was an oral poem now written down or a subsequent vernacular lyricization of Bede’s own Latin paraphrase.” Heaney’s life’s work also hovers on the borderline between oral and inscribed, an old life and a new vernacular. His identification with Caedmon was close enough to take the form of a poem in The Spirit Level, but it is revealing how he portrays him:

I never saw him once with his hands joined

Unless it was a case of eyes to heaven

And the quick sniff and test of fingertips

After he’d passed them through a sick beast’s water.

Oh, Caedmon was the real thing all right.

What makes Caedmon “real,” this seems to imply, is his nonconformity to religious routine. He is connected to both what is above and the beast below by the “sniff and test of fingertips.” It is this spiritual language that predates Christianity and therefore can also post-date it that Heaney was seeking in his own poetry, and it is the long Irish, Celtic, Gaelic and Norse roots of English that Heaney was attending to during a translation career that began with a deferred scholarship at Anahorish Primary School—where Master Barney Murphy gave Heaney his first lessons in Latin and also made “a stab” at teaching him Irish.

His final publication was a full translation of Book VI of the “Aeneid,” the favorite book of his secondary school Latin teacher, the Rev. Michael McGlinchey. The book gives a depiction of that very “Father’s embrace” that Heaney described in his “Beowulf,” but rather than the Christian afterlife, offers a classical and secular one: Aeneas’s reunion with his own father in the underworld.

What this collection shows is that quite aside from the long and magisterial commissioned works of translation that dominate the back of the book, Heaney spent his life investigating the far flung corners of English poetry’s roots and tributaries. Ted Hughes’s response to the news of Heaney’s Nobel Prize was “Like a sea-god on a great wave you emerged and inevitably took it [the Prize] by sovereignty of nature.”

He did emerge, but in ripples as well as that great wave. He was a one-man maintenance person taking stock of what he considered his own inheritance and keeping it in fine fettle. It may have been “Beowulf” for which he received the Nobel, but it was all these little poems from Caedmon onward through Virgil to Dante to Eastern Europe and its Catholic recusants to communism that were the actual carbuncles and weeds on the face of the hull. Heaney’s mind took in the whole language and its works as his territory in a way that neither Hughes nor Larkin, as his English seniors, nor Yeats as his great Irish predecessor ever did.

In that sense, it was the translation work that quietly marked him out for that Nobel. He read his poems everywhere, but he was also a poet people turned to because he could lend gravitas and honest feeling to a poet whose spiritual life had to be carried over into vernacular English in a secular age. Heaney was the go-to poet for last rites and for resuscitation.

They are still in Hallaig,

MacLeans and MacLeods,

all who were there in the time of Mac Gille Chaluim:

the dead have been seen alive.

Heaney described the effect of Sorley Maclean’s Scottish Gaelic poetry as “being led into some uncanny zone, somewhere between the land of heart’s desire and a waste land created by history.” What Heaney chose to translate, having heard Maclean read it, was a late poem from the 1950s, one “haunted by the great absence that the Highland clearances represent in Scots Gaelic consciousness.” Heaney’s version captures the great longing for a spiritual past and a spiritual redress, a great longing for what can only be recaptured in the afterlife; where Maclean was writing about the Highland clearances, Heaney was writing about the loss of a way of life in Mossbawn, a way of life that was already on its way out with the clerical reform of the Irish church, let alone with the tide of secularization and loss of public faith.

Heaney is lamenting the death of God in his own neighborhood ,where Matthew Arnold had lamented “the melancholy long withdrawing roar” of the Sea of Faith. It is quite a difference: One mourns what Sophocles once heard, the other what he himself heard in his mother’s front room.