“Rolling Stone started with the assumption that music was of infinitely greater importance to an upcoming generation of Americans than anyone had ever thought it was before,” says the magazine’s consulting editor Ralph Gleason, early in Alex Gibney’s two-part HBO documentary “Rolling Stone: Stories from the Edge.” “And we were right!”

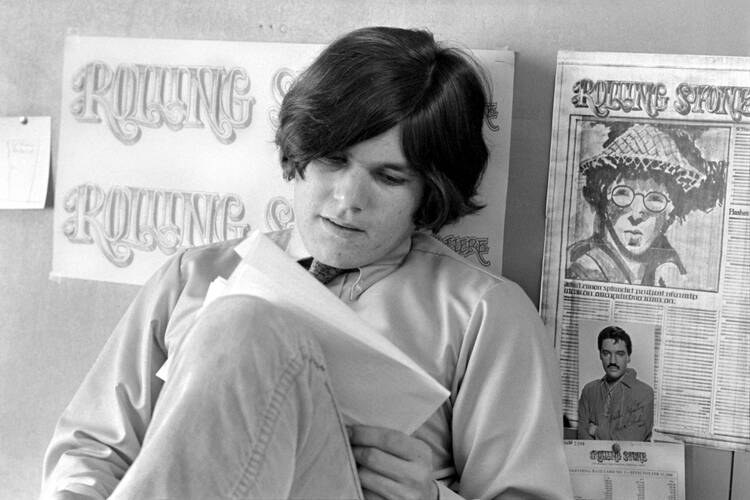

They were right and then some. Gleason was videotaped just six years after he helped his then-21-year-old acolyte Jann Wenner launch one of the most successful magazines of its time. As Rolling Stone celebrates its 50th anniversary, it is doubtful that Gleason—a legendary San Francisco Chronicle jazz critic who died in 1975 at the age of 58—would still recognize the magazine. But there is no doubt that the culture we live in has been significantly shaped by Rolling Stone and the vision of its editor and publisher Wenner, now 71.

Gibney’s “Stories from the Edge,” which was executive produced by Wenner, is essentially a greatest hits of the magazine’s major journalistic milestones and personalities—Hunter S. Thompson, Annie Leibovitz, etc. But it does not cover Rolling Stone’s single most compelling story: the making of Jann Wenner himself. The self-described “first child of the baby boom” has fashioned the magazine in his image and in the process made himself into an avatar of his generation and a major cultural gatekeeper for half a century.

The self-described “first child of the baby boom,” Jann Wenner is not happy with a new biography.

To get the story that Gibney could not tell, we are fortunate to have Joe Hagan’s Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine, an exhaustively researched and immensely readable tome that is as much cultural commentary as pure biography.

“Jann Wenner’s life tells the story of a man and his generation,” writes Hagan. “It is also a parable of the age of narcissism. Through image and word, Wenner was a principal architect of the rules of modern self-celebration—the ‘Me’ in the Me Decade.”

To understand the “Me” at the core of his story, the author spent 100 hours in conversation with Wenner and was given access to the mogul’s extensive personal archives. He also conducted 240 interviews with people from his personal and professional lives. Before its publication, however, Wenner publicly distanced himself from the book.

“Rock and roll set me and my generation free musically, socially and politically,” Wenner said in a public statement. “My hope was that this book would provide a record for future generations of that extraordinary time. Instead, he produced something deeply flawed and tawdry, rather than substantial.”

Hagan’s account will never be confused with hagiography, but it certainly does not have the earmarks of a hatchet job either. The 46-year-old writer—a self-avowed record nerd and music obsessive—told me he has come to terms with the fact that some “people are so reverent about Rolling Stone and the history of rock ’n’ roll that it made it difficult for them to have the nostalgia stripped back to look at it in a more straight, affectless way.”

Wenner appears to be someone who is breathtakingly unburdened by the weight of self-awareness or self-reflection.

Simply put—through his own words and those of friends and colleagues—Wenner appears to be someone who is breathtakingly unburdened by the weight of self-awareness or self-reflection. (Wenner has also been caught up in the tide of recent allegations of sexual harassment. He denies the story.)

In Sticky Fingers it is difficult to distinguish between Wenner the man and his appetites. It is as if he has confused “being” with “consuming.” Wenner’s denunciation of Hagan’s biography conjures up the image of someone who has finally looked up from the table after endless feasting and does not like the image he sees in the mirror. Perhaps in that reflection there is some recognition that the freedom he and his generation valued so highly for so long might have been something else in disguise?

Beating up on the baby boomer generation has become almost as clichéd as boomers themselves. The truth is Ralph Gleason was right that music had become infinitely more important to this generation. The problem was with their expectations about what that music meant and what it could accomplish. A song is far too fragile a foundation to base a life on. As beautiful and transcendent as it may seem, rock and roll—or any great art—won’t save the world. It simply cannot bear that weight. The burden of real life is far too great. Even at its most profound, art is simply an intimation, a glimpse of transcendence. It is not truth itself but a divine promise pointing toward the truth.

Sticky Fingers is the story of what happened when the freedom—that once appeared to be an end in itself—outlived its usefulness as a belief system. For Jann Wenner and many others it became an inflection point at which, according to Hagan, “they just pivoted into money.” There is nothing inherently wrong with money, it is just a poor substitute for transcendence.

“Beyond just Jann the man,” Hagan told me, “this is a cultural history and it shows you a little bit more about just how ambition was at the heart of so much of this stuff. Old-fashioned, old-as-time ambition. When you put ambition into the center of that story it changes the story.”

Music can be an idol just like any other human endeavor. The story of Jann Wenner seems to be a fairly typical story of idolatry and its effects on a person.

Not sure he's really typical of anything...