“How far back do you want me to begin the story?” Aisha Elliott asked me.

I told her to start with whatever she felt was best.

“Well, I came into contact with Hour Children while I was incarcerated, serving 25 years to life for a second-degree murder charge,” she began.

Ms. Elliott’s voice sounded firm and self-assured. She was calling me from Cleveland, Ohio, where she moved in 2020 to leave New York, the state of her upbringing and her incarceration. She had spent 21 years in the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, two in the Albion Correctional Facility and two in the Taconic Correctional Facility.

Ms. Elliott entered prison as a 20-year-old in 1992, and like more than 60 percent of incarcerated women in America today, she was a mother of children under age 18. At the time, she had no idea if or how she would see her toddlers, then 1 and 3 years old, again.

The statistics were not in her favor: A 2020 report from the Department of Justice found that incarcerated women lose parental custody at some of the highest rates of any parents—including parents whom courts have found abusive or neglectful. Children with mothers in prison are significantly more likely to face jail time and homelessness across their lifespan.

Children with mothers in prison are significantly more likely to face jail time and homelessness across their lifespan.

But Ms. Elliott managed to beat these odds, with the help of an organization that enrolled her in parenting classes during her sentence, provided her housing when she came home on June 2, 2016, arranged for her first job out of prison and trained her for her second. That organization is called Hour Children, and Ms. Elliott said that without it her family would be in pieces.

“My kids are my absolute best friends. Now we have the greatest, coolest relationship, and there’s no way that I can attribute that to anybody other than the parenting center and the courses I took,” she said.

Since 1992, Hour Children has helped hundreds of women like Ms. Elliott reintegrate not only into society but into their family lives. The Queens-based nonprofit applies a uniquely holistic approach to helping incarcerated women, with a presence inside women’s prisons in New York State and in the lives of inmates after release in New York City. Their initiatives aim to prepare women during their sentence for re-entry into society and then provide support after it ends.

This mission informs everything about Hour Children, including its name, which is a reference to three crucial times for an incarcerated mother’s relationship with her child: the hour of her arrest, the hour of their visit while incarcerated and the hour of their reunification upon release.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Hour Children, which has grown from an unassuming but adamant voice of advocacy for imprisoned women to an essential presence in several of New York State’s female correctional facilities.

Since 1992, Hour Children has helped hundreds of women like Ms. Elliott reintegrate not only into society but into their family lives.

Everyone I spoke to, from current employees to alumnae of the program, credited the nonprofit’s success to one woman: its founder, Teresa Fitzgerald, C.S.J., known affectionately as Sister Tesa. It was her vision three decades ago that launched Hour Children out of a run-down convent building in the Queens neighborhood of Long Island City.

An Unplanned Ministry

Sister Tesa retired as the executive director of Hour Children in July 2021 to begin her tenure as president of her religious order, the Sisters of St. Joseph. She joined the order immediately out of high school in 1964. Her parents, both Irish immigrants, had raised her in the hamlet of Hewlett, N.Y., on Long Island.

She encountered the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph while in Catholic school, just as she was discovering her own interest in education. By the time she graduated, she had discovered her vocation. “They were wonderful role models and good people, happy people. That’s why I chose to do it. I never regretted one second,” Sister Tesa told me.

She began her career as an educator, teaching and serving as a principal in several Catholic schools on Long Island. She loved working with children and had no plans to change her ministry.

But her work took an unexpected turn in 1979, when another Sister of St. Joseph, Elaine Roulet, invited members of the congregation to join her in helping incarcerated women. Sister Elaine had been working with mothers at the Bedford Hills facility in Westchester County, N.Y., since 1970, advocating for a playroom and a nursery inside the prison. Now she wanted to help inmates rebuild their families upon their release.

Sister Tesa joined Sister Elaine to start Providence House, initially founded as a place for women to live once they came home from prison, hoping to connect with their children. Soon after, Sister Tesa started looking for a permanent place where children could stay and visit their mothers during their prison sentences.

In 1986, as she was pursuing this idea, she realized a convent building could provide a suitable location for the new service. Her religious order had a presence in St. Rita’s Catholic School in Long Island City, and some of those sisters told her that the pastor at St. Rita’s would be willing to sell the old convent next door.

Sister Tesa started looking for a permanent place where children could stay and visit their mothers during their prison sentences.

“We met one night, the dark of night, and he was just very open and supportive of it all,” Sister Tesa said. “We negotiated everything on the sidewalk.”

She called that facility My Mother’s House, and it remains part of the Hour Children network today. For nine years, the ministry that would become Hour Children operated out of that convent. Sister Tesa said that all the sisters trained as foster parents, and a group of children lived with them during their mothers’ sentences; the sisters frequently drove the children 45 miles north to Bedford Hills for visits.

Before long, Sister Tesa expanded the work of the organization to assist formerly incarcerated mothers beyond just caring for their children. She incorporated and officially named the organization in 1992. Her guiding principle when she founded Hour Children remained the same throughout her tenure as head of the organization: “Listen to the people you serve.”

“You don’t put your own expectations out there, your own vision,” Sister Tesa said. “You listen to their stories, and you listen to the stepping stones they needed to really move forward with their life.”

This principle developed into Hour Children’s current model of providing tools for success during prison as well as housing and job resources after release. Sister Tesa began building up Hour Children’s offerings in Long Island City, purchasing new buildings to house more women during their re-entry, while she built up services available within prisons.

Those in-prison programs included parenting classes, Ms. Elliott’s early introduction to Hour Children in 1995. She said she took classes entitled “Parenting From a Distance” and “Parenting Through Films.” Slowly, she became more involved with Hour Children and started working in the parenting center herself.

“Listen to the people you serve. You don’t put your own expectations out there, your own vision.”

Ms. Elliott said she initially gravitated toward Hour Children because Sister Tesa was eyeing new housing opportunities for women without small children, and her own daughters would be adults by the time she left prison. She knew she would need somewhere to go when that day came.

During her 20-year involvement, Ms. Elliott developed a relationship with and deep affection for Sister Tesa, the slight, smiling Irishwoman wearing a gold crucifix who seemed simultaneously at ease and in charge while working at Bedford Hills.

Upon her release, Ms. Elliott moved into an Hour Children house. By that time, Sister Tesa had built a system for re-entry that provided women a wide range of tools they might need to succeed after incarceration, both as citizens and as mothers.

Sister Tesa had listened to the post-incarceration struggles of her clients and responded to them. She had expanded housing offerings, career paths and child care services to take care of a range of her clients’ needs. Hour Children has become a national model for assisting re-entry, earning Sister Tesa recognition from the Obama administration, CNN, Irish America magazine and others.

As she begins a new phase of her vocation, Sister Tesa said that she will lead the Sisters of St. Joseph with the same principles of love and mercy that guided her at Hour Children. She is especially fond of a maxim often attributed to St. Francis of Assisi: “Preach the Gospel. When necessary, use words.”

“That’s a very important piece of the Gospel message for me, that we look at people and accept people for who they are, and don’t use labels,” she said. “Every human being is really important in God’s eyes. There’s no such thing as a castout, ever.”

Houses and Homes

On a weekday afternoon, the block of 12th Street between 36th and 37th Avenues in Long Island City echoes with the laughter of children. Among the low, discolored brick buildings and chain link fences are several schools—public, charter and Catholic, all within a three-block radius—along with a library and playground nearby. When recess starts, everyone knows it.

It is a fitting neighborhood to house Hour Children.

Rubernette Chavis, the director of mental health initiatives, walked me around the block and took me into the Hour Children buildings. On the way, we passed a hair salon founded and run by one of Hour Children’s former clients. Ms. Chavis pointed out businesses that donate food or services to the charity.

“I know, whenever I get pizza, to go to that pizza parlor because they help us out,” she said, pointing to a storefront across the street that provides coupons and gift certificates for Hour Children events and fundraisers.

The array of services now provided by Hour Children reflects the complex and often interrelated needs of women caught in the justice system.

We headed into My Mother’s House, that first housing facility purchased by Sister Tesa more than 30 years ago. It was immediately clear that this used to be a convent, with its wide communal dining room and kitchen.

Hour Children has made the space its own since then. No two walls are painted the same shade of bright green or purple or blue. The basement has been converted into a day care center.

A lot has changed in the organization since its founding. The array of services now provided by Hour Children reflects the complex and often interrelated needs of women caught in the justice system. Programs in the prison facilities and in Queens work in close relationship to give clients the best shot at successful reintegration.

In Bedford Hills prison, “everybody knows Hour Children,” said Christina Illenberg, an executive assistant. She spent 25 years incarcerated, most of it in Bedford Hills, and she said that she spent about four of those years working for Hour Children before her release in 2020.

Hour Children runs the nursery there for women who give birth while in prison. Thanks to the efforts of Sisters Elaine and Tesa decades ago, working in tandem with dedicated and driven women inside, mothers can live with their child for up to 18 months after birth. That time is crucial, not only for the emotional wellbeing of mother and child but also to allow the mother to figure out what comes next. Some women are released in time to go home with their babies. Others must start making plans and heartbreaking decisions about custody for the child.

Thanks to the efforts of Sisters Elaine and Tesa decades ago, working in tandem with dedicated and driven women inside, mothers can live with their child for up to 18 months after birth.

Judy Clark did not give birth in prison, but her daughter was only 1 year old when she was arrested in 1981. Ms. Clark was a key player in building Hour Children’s initiatives in Bedford Hills during her 38-year sentence. She said that she began working with Sister Tesa from her earliest years inside.

“The children’s center was a major part of the experience inside,” she said. “It was a community in which we built the programs to address the issues we experienced.”

Ms. Clark remembers the development of the curriculum for the classes that Ms. Elliott took, focused on how to parent from prison. She said that women would write letters and record bedtime stories on tape to send to their children. Similar methods are still taught in the Hour Children parenting centers.

Ms. Clark said that Hour Children’s growth was spurred by the changing needs of the women involved. When it started, she said, most of their clients were young mothers. But when that changed, the options had to expand.

“As our children grew, we saw new needs. As our children became teens, we knew that the kids in their teen years needed different experiences with each other and with us,” she said.

“It was a community in which we built the programs to address the issues we experienced.”

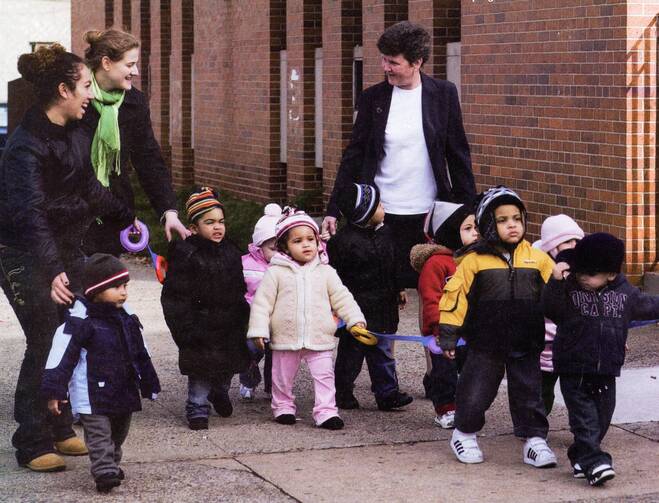

One thing that did not change, however, was the organization’s focus on physical visits. The visitation program has retained the same mission and basic format since the 1970s, transporting children to reunite with their mothers inside, even as its capabilities have grown. At the maximum-security Bedford Hills prison, Hour Children provides a week-long overnight experience in partnership with local host families. This past summer, 35 children stayed in nearby homes and made use of every minute of the prison’s seven-hour visiting time each day.

As a result, children can come from all over the state instead of just nearby New York City. Once that program began, Ms. Elliott’s children visited her from Utica during her time in Bedford Hills—a 220 mile journey only made possible by a host family.

Post-Prison Success

The ultimate goal of all of these in-prison initiatives is to set women up for success upon their release. Many women seeking to become clients of Hour Children undergo an intake process and interview while still incarcerated. Ms. Clark spoke about a “mutual commitment” made between the two parties.

That is because Hour Children means more than just affordable apartments, as Ms. Chavis explained to me. It is a comprehensive program. Women who qualify to live in My Mother’s House fall in Population G of New York’s supportive housing laws; they either have a disabling medical condition or a substance use disorder. Other houses offered by the organization serve other at-risk populations.

Most women in the program will move through communal housing and into permanent housing, but all go through at their own pace. When Ms. Elliott left prison in 2016, she came to the Hour Children house in Richmond Hill, a neighborhood to the southeast of Long Island City. Hour Children allowed her to tour all of the facilities, including the more independent housing that she would move into later. Ms. Elliott said that one apartment in Flushing called to her.

“When it’s my turn to live independently, this is where I want to live,” she recalled thinking. “Now that I’m in an entire house, it was just a room. But when you’re coming from a cell, that room looked really big.”

“Now that I’m in an entire house, it was just a room. But when you’re coming from a cell, that room looked really big.”

Not every room at Hour Children houses mothers and their children together. At My Mother’s House, for example, only five of nine apartments host families with young children. Ms. Elliott said that she determined during her exit interview with Sister Tesa that it would be a bad idea to try to move back in with her family in Utica. Widespread substance abuse and a lack of job opportunities would likely have landed her back in prison. But she also needed her own space to adjust to the realities of 25 lost years.

“Even when they’re 30 and 32, they’re still 1 and 3 in your mind. You can’t go home to grown folks and be mommy. It just destroys relationships,” she said.

The employment-focused Hour Children program, called Hour Working Women, is also based in Long Island City. It currently provides education and job trainings for 36 clients. Recent offerings have ranged from electrocardiogram and medical assistant training to culinary classes. Hour Children works one-on-one with women to find job opportunities, providing footholds that allow them to start making money and paying bills.

In the most recent cohort of 12 women who completed certified medical assistant training, 10 have been placed in paid internships, and eight are negotiating job contracts for after their internships end.

Programs in the prison facilities and in Queens work in close relationship to give clients the best shot at successful reintegration.

Ms. Elliott trained as an electrician and joined a local union, working on the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, among other projects. She enjoyed the work, even though she did not ultimately remain in that job.

As she moved through her re-entry, Ms. Elliott found the most independence and self-reliance that she experienced since 1992. When it came time for her to leave Richmond Hill and have her first personal, private space in 25 years, the room she had yearned for in Flushing was available.

Ms. Elliott was ecstatic.

The Hours to Come

The administrative offices of Hour Children occupy the basement floor of one of their residential houses; its employees work in the same building where its clients live.

Dr. Alethea Taylor began her tenure as executive director of Hour Children in January of this year, taking over for Sister Tesa. She was previously a distinguished lecturer on education and counseling at Hunter College, a role she enjoyed, she said, but that was not as fulfilling.

“I wasn’t living my purpose. And my purpose is to serve women who are formerly incarcerated or justice-impacted, to help them and guide them towards choice and having a voice,” she said.

“My purpose is to serve women who are formerly incarcerated or justice-impacted, to help them and guide them towards choice and having a voice.”

Dr. Taylor has never been incarcerated but grew up with family members who were in and out of prison. She saw how people who were left on their own after incarceration were set up for failure when applying for jobs or housing. She witnessed the many injustices of the American justice system. In her new role, she said that she hopes to grow Hour Children’s advocacy work and prevention services while still providing its core offerings.

“Hour Children really needs to be a voice in the community and be a voice in the political realm about the issues,” she said.

For now, this job falls primarily to Ms. Clark, who works as Hour Children’s first-ever community justice advocate. Ms. Clark works with city and state government to take action on the needs of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people.

One gaping hole in the justice system, Ms. Clark said, is that conversations about life after incarceration tend to start far too late into each person’s sentence, leaving people scrambling and unprepared to return to their lives. “We need a system that looks at re-entry not at the end of your sentence but at the beginning of your sentence,” Ms. Clark said.

Ms. Clark and Dr. Taylor hope Hour Children can help change policy, addressing the root causes of post-prison homelessness and unemployment as well as treating their symptoms. Ms. Clark is currently fighting for the Fair Chance for Housing Act in New York City, which would outlaw discrimination by landlords against people with conviction records.

Ms. Clark is currently fighting for the Fair Chance for Housing Act in New York City, which would outlaw discrimination by landlords against people with conviction records.

Dr. Taylor said she hopes to broaden the scope of Hour Children re-entry services. She wants to expand family therapy, allowing the broken bonds between a mother and her partner or a mother and her own parents to heal. The primary focus has always been on re-establishing the mother-child relationship. Dr. Taylor wants women to have the option to extend that to other family members who might hold onto resentment.

Dr. Taylor also emphasized the work that remains to be done within Hour Children itself. When she arrived, she said that staff had brought concerns to her about diversity and inclusion within the organization. “We’re an organization that is predominantly serving people of color, but our staff don’t necessarily match our clientele. So that’s something that we will be working on,” she said.

Dr. Taylor does not believe in filling anyone’s shoes (“Everyone walks their own journey,” she said), but she does hope to continue Sister Tesa’s core mission.

“As the founder of this organization…she thought so succinctly about every aspect of a woman’s need, and built that into the organization,” Dr. Taylor said. “That’s someone that’s really thinking about the home and the whole person.”

Hour Children will continue to pry open doors that society has closed on incarcerated women.

Hour Children will continue to pry open doors that society has closed on incarcerated women. As far as Ms. Elliott in Cleveland is concerned, their model for re-entry support is unmatched.

Ms. Elliott came into prison as a high-school dropout, but quickly earned her G.E.D. and began taking university courses through a Mercy College program inside Bedford Hills. When President Clinton’s 1994 crime bill threatened access to those classes by denying Pell Grants for incarcerated women, she and Ms. Clark fought together with others to build their own program with Marymount Manhattan College. She left Bedford Hills a college graduate.

Now she works remotely for Columbia University’s Justice Lab, conducting research on mass incarceration across the country. Her work currently focuses on conditions in the state of Oklahoma.

On the day she left prison, Ms. Elliott remembers, she was released directly into the responsibility of Hour Children. They had met with her as she prepared for release, helping with tasks as fundamental as securing a state ID and as small as learning to use an iPhone. Now someone from the organization would be there waiting for her to take her to Queens for onboarding.

At least that was the plan. But Sister Tesa made an exception for Ms. Elliott, one she will “forever appreciate.”

Her daughters picked her up instead.

Christopher Parker is a Joseph A. O’Hare fellow at America Media. His work has been featured in Notre Dame Magazine, Arches Magazine, the Los Angeles Times and the Berkshire Eagle.