Academia Nuts

A college president who is not already a wee bit nuts might easily become so when exposed to the competitive dysfunctionality and rampant absurdity that pass for normal behavior in the academy. But while curious characters abound, no university leader is quite so unhinged as M. R. Neukirchen, the improbable president of a fictional university in New Jersey that strongly resembles Princeton, the author’s academic home.

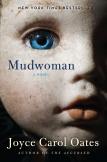

Joyce Carol Oates has surpassed her own rather high standards for strangeness in portraying the emotionally ill protagonist of Mudwoman, a child abandoned and left for dead in remote Adirondack mudflats. Rescued, she climbs to the heady heights of academic leadership, only to suffer spectacular meltdowns as the stress and loneliness of the college presidency unleash long-repressed memories.

Oates seems to have it in for women leaders. People who think that women are too unstable to be reliable leaders will love this book. The rest of us who have spent years trying to be taken seriously as women leaders are left to wonder with some irritation why Oates chose a madwoman—Mudwoman—to be the first president of a prestigious university.

Despite the setting, this book is not really about academia, but rather about the appalling psychological damage of child abuse. M. R. Neukirchen’s unraveling is not because of her position (though stress may be a trigger for some of her more bizarre behaviors) but rather because of long-unresolved emotional issues from her abysmal childhood. Absent good counseling, which apparently M.R. never had, she would have come apart in just about any job by the time she hit mid-life.

Certainly, parts of Oates’s narrative are familiar to academic leaders, some in a chilling way. I happened to read the first part of the book on a weekend when I had escaped my own responsibilities as a college president, leaving no forwarding number as I roamed the desolate tidal marshes of Bombay Hook along the Delaware coast, where the peace and quiet are always restorative. Later, in my hotel room, as I read the first chapters, in which President Neukirchen skips out of a professional conference to make a secret drive north to the Adirondack mudflats of her repressed memories, I shuddered in recognition of the irresistible urge to abandon all duties, to leave no forwarding numbers, to drive fast and far away from a room full of people waiting for the president’s major speech. Most of us manage to get a grip.

For President Neukirchen, the line between hallucination and real life is blurred, and Oates plays games with the reader as the narrative shifts without warning from reality to fantasy. Left to die as a toddler on the muddy banks of the Black Snake River by her mentally ill mother, Jedina Kraeck never conquers her fear of abandonment. Rescued by a trapper, Jedina claims the name of her lost sister Jewell as a renunciation of the self she left buried in the mud. Later adopted by a kindly Quaker couple, she becomes Meredith Ruth Neukirchen, a good girl known for her scholarly ways, strength and competence, and deep desire to please others.

Academic success takes M.R. first to Cornell and then Harvard, where she meets her astronomer lover, who is, quite simply, a narcissistic jerk. He forces her to leave Cambridge after graduate school—“exiled” is M.R.’s word—to find a position at the New Jersey university because he, Andre Litovik, is also married and does not really want his mistress around. Her obsession with Litovik and desperate desire for his love and affection, which he is utterly incapable of sharing with her, is another thread in the theme of loneliness and lovelessness that winds through this book like the coldest, darkest river of dreams. Oates wrote Mudwoman after her own beloved husband died, and the book’s alternate subtitle “A Widow’s Story” suggests autobiographical threads that may partially explain M.R.’s shattered psyche in search of love as she roams across bleak landscapes.

Professor Neukirchen becomes an academic star at the New Jersey university, climbing the ladder to the presidency; her selection vindicates her need for approval. A reader more familiar with modern presidential search methodology might wonder how someone so emotionally fragile got past the first round.

There are almost no sympathetic characters in this book. As M.R. quickly devolves into madness during her first year living alone in Charter House, the historically dreary president’s residence, her staff are mere foils at the edges of consciousness like flighty sparrows who cannot match the ominous presence of the King of Crows, whose cries on cue signal the darker passages of Oates’s strange dreams. She has an unpleasant encounter with a disturbed student, whose fate becomes a weird thread in the story. She falls down steps, wears heavy makeup to obscure her injuries (Oates revealed in an interview that this image came to her in a dream), is late for meetings with trustees and big donors and seems distracted in ways that signal serious deterioration of a rational personality.

For anyone acquainted with the rage that the slings and arrows of academic administration can kindle in even the kindliest of souls, the dream sequence in which President Neukirchen kills and dismembers the leader of her faculty opposition is delicious depravity. In today’s collegiate environment, such a dream would have the president taken hostage immediately by the Campus Threat Assessment Team.

Ordered to take time off to rest and recover, M.R. goes on a journey to confront her childhood demons. She discovers the goodness of her adopted father and the empty-eyed existence of her aged birth mother. After more meanderings through mudflats, her lover calls and wants her back, and we last see her driving south on I-81 toward New Jersey, allegedly free of her demons. I do not think so. She is running back to the arms of Andre Litovik, her presidency a mere afterthought. If I were her board chair, I would buy out her contract immediately.

Mudwoman is entertaining, but also highly improbable. Oates writes with her usual careful attention to detail and colorful descriptions of locations, but unfortunately, her characters come across as depressing stereotypes. Mudwoman can be a good beach book, but among Oates’s works, I much preferred the Wonderland Quartet.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Academia Nuts ,” in the November 4, 2013, issue.