American Christianity is shrinking. Many scholars and religious thinkers have probably had this sense for a while, but numbers were recently published that back this up. Last October, the Pew Research Center released a study that confirmed the continued demographic shift away from Christianity in the United States. In the wake of these findings, many solutions have been put forward by those troubled by the church’s decline.

Most of the proposals have been fairly standard: better liturgy, better catechesis, more focus on social justice. Depending on one’s doctrinal stance, either recommitting ourselves as a church to certain positions to show our distinct identity or abandoning them altogether to show our openness to the world have been suggested yet again. The suggestions usually say more about the pet interests of the one suggesting and perhaps generate more heat than light.

Stephen Bullivant’s recent book Mass Exodus, which looks at the phenomenon of ex-Catholics in the United States and Great Britain, can help us make sense of all this. Bullivant’s work has already sparked excellent conversations. Reviewing the book for America, Timothy P. O’Malley concurs with Bullivant that “disaffiliation is rarely a single moment in the life of a Catholic. Instead, it is a process in which one no longer identifies as a Catholic.”

“Disaffiliation is rarely a single moment in the life of a Catholic. Instead, it is a process in which one no longer identifies as a Catholic.”

The Grammar of Assent

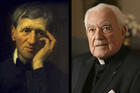

For someone like the newly canonized St. John Henry Newman, this conclusion would come as no surprise. Newman’s whole life was dedicated to pondering how we may know the truth, especially in matters of religion. The answer he came back to time and again: It is complicated. Nor is this complexity restricted to matters of religion. Belief of any sort is a complicated matter.

Among Newman’s chief intellectual foes were Enlightenment thinkers who attempted to make human knowledge a matter of geometric logic. Newman railed against the Enlightenment doubt championed by René Descartes and turned into brutal skepticism by David Hume. We may want humans to be algorithm-following belief machines, taking one logical strain from beginning to end and believing or not based on the conclusion, but this is not how humans actually work.

Regarding mental functions like doubt and certitude, Newman declared in his Grammar of Assent that “our duty is, not to abstain from the exercise of any function of our nature, but to do what is in itself right rightly.” Sometimes we doubt, and sometimes we are certain; both can be good.

Newman is not interested in how Enlightenment thinkers believe human beings ought to know things but rather in how we actually know. The reality is far messier than the ideal. We do not follow a clear and distinct logical chain from beginning to end, from premise to conclusion. We take in a whole world at once and make our decisions based on this experience.

Newman is not interested in how Enlightenment thinkers believe human beings ought to know things but rather in how we actually know.

The Messiness of Reality

Bullivant’s observations track quite well with Newman’s. Bullivant observes that while there may be one or two reasons expressed for leaving Catholicism, the reality is usually far messier. This is not to say that the reasons or experiences people give for their departure are not the most important ones, just that they are far from the only ones.

Embodied reality is complex, and so is our way of knowing. This is one of Newman’s key points. It is true of how we believe (or doubt) claims in general, and it is true of how we believe or doubt religious claims. What Newman refuses to do as he explores the ways in which we believe or doubt a religious claim is to treat it as a form of belief altogether different from any other.

Religious belief is, in many respects, like belief in any other class of knowledge. That is to say, our motives for belief or doubt in the religious sphere have a strong family resemblance to our motives in other spheres of life. What we are saying “I believe” or “I doubt” to is different, but why we say it is generally the same. The process itself is the same.

Newman was not the first person to observe that we believe in religion for the same reasons we believe in other areas of life. He was, however, among the most forceful advocates of this idea. Moreover, because he was surrounded by the cultural legacy of the Enlightenment (like all of us in the West today), Newman had to defend his theories about belief against Enlightenment objections.

Our motives for belief or doubt in the religious sphere have a strong family resemblance to our motives in other spheres of life.

Knowledge and Belief

Among the strongest Enlightenment objections that Newman tried to answer is that the best knowledge is abstract. Beginning with Descartes, thinkers had tried to know and believe rightly by removing themselves from the world. If we remove ourselves from the world and structure our thoughts according to mathematical logic, they argued, we will believe only truth.

Newman would have none of this. We know from being immersed in the world, he insisted, not removed from it. We are not all mathematicians, and while logic may clarify our thinking, “logic is open at both ends.” What counts as evidence for analysis and how the conclusions will be applied are not part of the logical chain itself. There is more to belief and doubt than a single argument, no matter how well constructed it may be.

As O’Malley reminds us at the start of his review of Bullivant’s book, leaving Catholicism is a process. Newman’s ideas of knowledge and belief help us to understand why this is the case. No one thing convinces us. It is a series of arguments and experiences that eventually have a cumulative effect.

Theory and logic help us to make sense of things, but it is reality, with all its complexity, that seizes the mind and incites belief.

It was the cumulative effect of evidence and experience that brought Newman himself into the Catholic Church. His experiences of his conscience, his observations of history, his doctrinal concerns, his own experience of Catholics—all of these things together, in addition to a whole host of other elements, came together for Newman until one day they could no longer be ignored.

The process by which Newman came to Catholicism is in many ways the reverse of the process that Bullivant gives us of so many who have left the church. Newman might have articulated a few key reasons why he became Catholic, but he would be the first to say there was far more to it than that. Those who cease to be Catholic (or Christian in general) may articulate a few key reasons for their departure, but there is almost always more to the story.

Belief is complicated. This is Newman’s central point in linking our knowledge so closely to reality: Reality, unlike theoretical constructs, is complex and gives our minds the complexity they need to believe. Theory and logic help us to make sense of things, but it is reality, with all its complexity, that seizes the mind and incites belief.

Anyone who claims to have a silver bullet for evangelization is selling something.

Both/And

If belief (and unbelief) is complex, then so is evangelization. The Pew report has sparked all the usual discussions about the “silver bullet,” the solution to the problem of lapsed and former believers. What Bullivant’s data and Newman’s insights tell us, however, is that there is no silver bullet. Anyone who claims to have a silver bullet for evangelization is selling something.

Christ has called us to evangelize and make disciples of all nations. But evangelization cannot happen by focusing on a few pet topics. We need a “broad front” strategy for evangelization. The issue with most proposals for evangelization is not that they are wrong but that they are not enough.

What Newman can remind us about evangelization and what Bullivant shows us about people leaving Catholicism is that there is never just one thing at stake. This means that our idea for evangelization is probably at least partly right but only if it is not to the exclusion of others’ ideas. We need all these ideas together, woven into the complex and marvelous tapestry that is Catholicism, to truly capture a heart. We need the famed “Catholic both/and” as we evangelize: liturgy and social justice and abuse reform and catechesis and....

No one project can win out. To evangelize is to show people the whole world of Jesus Christ, with all its complexity and messiness and beauty. Only the cumulative weight of it all can touch the whole person and foster religious belief in our modern world.