In 1142, a powerful Benedictine abbot traveled to Spain. Known as Peter the Venerable for his wisdom, he ruled a federation of 600 monasteries from his base at the Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy. The journey across the Pyrenees was long, and his agenda was packed with kings, bishops, abbots and complex negotiations. Abbot Peter’s visit to Toledo, which had been reconquered a few decades earlier after almost four centuries of Muslim rule, led him to a surprising decision. He summoned Christian scholars of Arabic and set them to work translating Islamic texts into Latin. Pre-eminent among them was the Quran itself, entrusted to an English cleric who had learned Arabic to gain access to scientific literature in that language, including Arabic translations of otherwise lost classical Greek texts.

What was this abbot thinking? He was not a scholar of comparative religion, as you might find in a modern university. He was a medieval abbot, facing a powerful and highly literate religious tradition he considered to be fundamentally incompatible with his own. His intention was adversarial. Nonetheless, he embraced the humanistic principle that to understand people of another culture, with different beliefs, we must listen to them in their own voice, learning their language, reading and understanding their texts.

To understand people of another culture, with different beliefs, we must listen to them in their own voice, learning their language, reading and understanding their texts.

As a Benedictine monk, Abbot Peter belonged to a community of readers engaged in the study of Christian sacred texts and related literature. That is the truth behind the familiar trope of a monk hunched over a copy desk, quill in hand, writing texts on reams of parchment: a belief in the power of words. Their labor of copying was for the sake of learning, learning for the sake of understanding, understanding for the sake of worship and thanksgiving. Abbot Peter could see that the same was true of the followers of Islam. That shared experience made intellectual engagement—and debate—possible.

We monks put down deep roots and try to cultivate through communal monastic practices the grounded humanity that Greek philosophers and their Christian heirs characterized as learning “to dwell with the self” (habitare secum). At its best, that monastic stability frees the mind to roam widely and to make unexpected applications of what is found. Alongside the theological tomes would be texts of philosophy, grammar and mathematics, astronomy and history, medicine and law. Benedictines have always been inventors or early adopters of technology. Clocks were developed in the Middle Ages to wake up monks for early prayers. The introduction of movable type and mechanical printing came as a great relief: The second book printed on Gutenberg’s equipment was a Benedictine psalter.

What about the manuscripts the European and American explorers and collectors never found? Or the cultures they were not interested in plundering?

What We Learn From Manuscripts

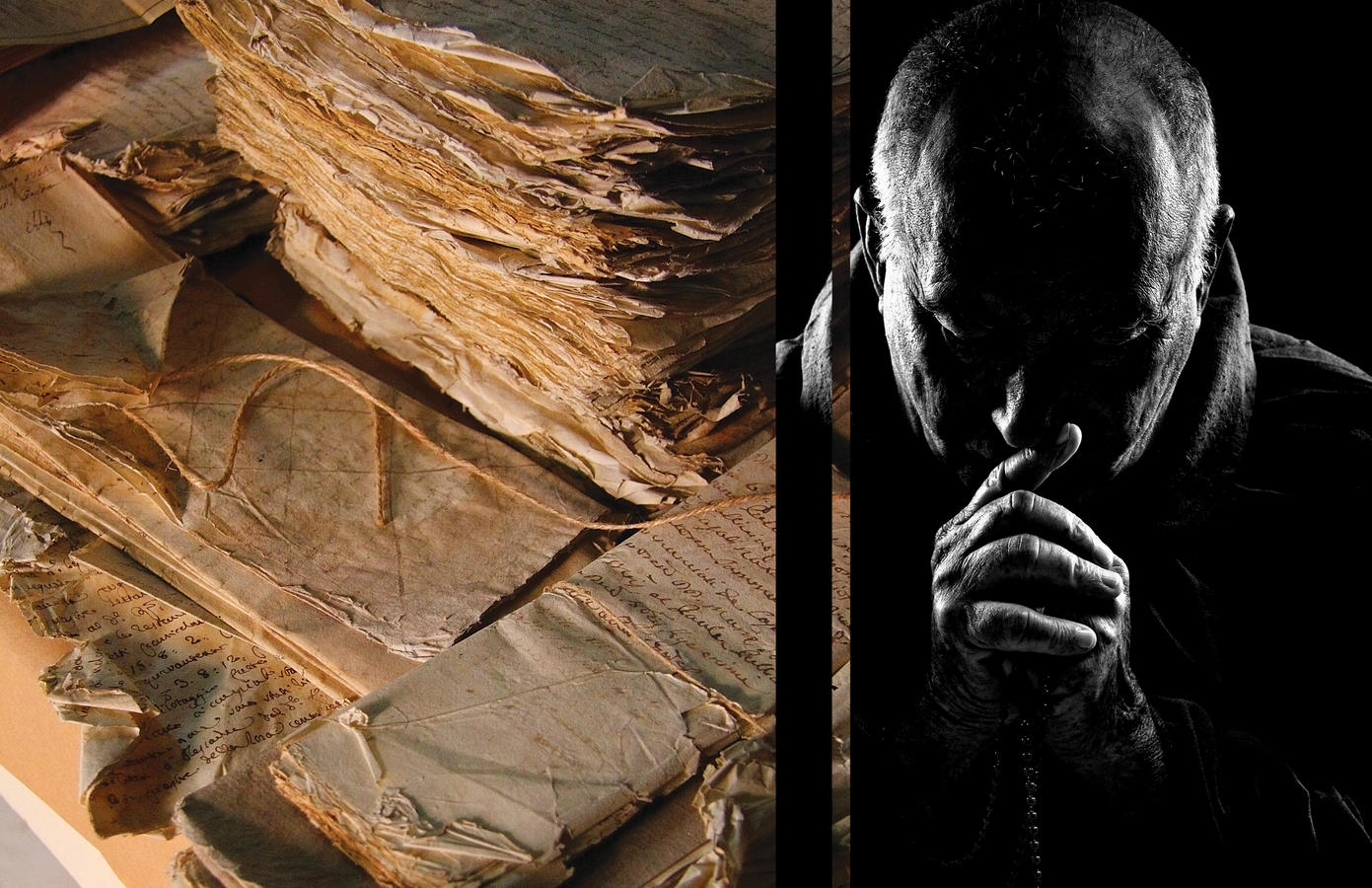

Even though manuscripts—handwritten books— are at least several technological stages behind the ways we access information today, we still rely on them for access to the past. Consider: Anything written before the invention of printing has come down to us in the form of a manuscript. A surprising number of those texts have not yet been printed or put online, and we keep finding new texts in manuscripts that have lain hidden for centuries. In many parts of the world, printing came late or was little used, so even less of the literature of these communities is available in modern formats. To know what is most important to such communities, to understand the questions they asked and what gave them purpose and identity, we need to read their manuscripts.

Manuscripts matter even for well-known texts, because each manuscript is unique. The texts will vary from the same writings found in another manuscript because there was no standard edition from which every scribe would copy. Those differences might be slight or substantial, even to the point of changing the meaning of the text. Scribes would “polish” a text by smoothing out the spelling or grammar, or they might amp up or tone down controversial passages. Nor were they infallible; they always made mistakes. The cumulative effect of those human interventions is that every manuscript must be approached on its own terms, as a particular incarnation of the writings it contains. Framing the text are readers’ notes in the margins, ownership inscriptions on the flyleaves, the scribe’s sign-off at the end. Together they form the manuscript’s cultural genome and allow us to place it within a cultural lineage.

The second book printed on Gutenberg’s equipment was a Benedictine psalter.

One will find thousands of manuscripts in the great libraries of Europe and North America on display and available for study, all of them cataloged and usually well known to scholars. Much of what we think we know about the past has been written on the basis of the manuscripts in the British Library, the Vatican Library, the French Bibliothèque Nationale and their peer institutions. Their collections of Latin and other European manuscripts are vast and comprehensive, accounting for the great majority of surviving Western manuscripts.

When we consider other cultures represented in the collections of those great libraries, our footing is less sure. All of those manuscripts came from somewhere else, often the spoils of war and colonial expansion, like many of the artistic treasures in major museums. The manuscripts taken to Western libraries provide only a partial view of their source cultures. To rely on them alone is akin to looking at a mummy in a museum display and assuming we understand ancient Egyptians. What about the manuscripts the European and American explorers and collectors never found? Or the cultures they were not interested in plundering?

Saving Cultural Treasures From War

The work I do today to preserve manuscripts began in 1965 as an effort by my monastery to microfilm Latin manuscripts in European Benedictine libraries. It was two decades after the devastation of the Second World War, three years after the Cuban missile crisis and during a very chilly phase of the Cold War. We feared that the European Benedictine heritage would be vaporized if there were a World War III. Monte Cassino in Italy, the mother abbey of the Benedictines, had been totally destroyed in 1944. A nuclear war would be far more devastating.

There was nothing we monks in Minnesota could do to protect the churches and cloisters, but we could microfilm their manuscripts and keep backup copies in the United States. The Vatican Library had done something similar in the 1950s, depositing microfilms of many of its manuscripts at Saint Louis University in Missouri. Our project started in Benedictine monasteries in Austria, employing local technicians to involve them in the preservation of their own heritage. The scope of the work soon widened to libraries of other religious orders, then to universities and national libraries. The pace was swift, and the result, by the end of the 20th century, was a film archive of almost 85,000 Western manuscripts.

Along the way there came a serendipitous event that changed the course of the project. An American scholar of biblical texts approached us with the idea of microfilming manuscripts in the monasteries and churches of Ethiopia. This great African nation is the home of an ancient Christian community that had never undergone the narrowing of the biblical canon—the official list of writings constituting the Christian Bible—that occurred in other parts of the early Christian world. Consequently, Ethiopian Christians preserved a broad array of writings later excluded from the Bible of the Byzantine and Roman traditions. Microfilming began in 1971, with the work done by Ethiopians, the technical support from us and funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, among other foundations.

The cameras kept going, working throughout the 1970s, 1980s and into the early 1990s. In the end, 9,000 manuscripts were microfilmed under often-harrowing circumstances.

The situation in Ethiopia worsened when a violent revolution deposed the emperor and installed a communist government hostile to the church. What had begun as a kind of archeological expedition to discover ancient texts became a rescue project to preserve manuscripts in a nation convulsed by political upheaval and then a civil war. The cameras kept going, working throughout the 1970s, 1980s and into the early 1990s. In the end, 9,000 manuscripts were microfilmed under often-harrowing circumstances.

The Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library also demonstrates what happens to manuscripts in times of turmoil. A few years back, a professor from Howard University approached one of our experts for help identifying an Ethiopian manuscript recently donated to the university. She showed him photographs of the manuscript, and he recognized it as one of the thousands microfilmed in our project. After it was photographed in 1976, the manuscript had been taken out of Ethiopia and found its way into a private collection in the United States.

Unlike most stories of this kind, this one had a happy ending: Howard University repatriated the manuscript to the monastery in Ethiopia from which it had been taken. Sadly more typical is the case of another, even more valuable, Ethiopian manuscript microfilmed in the 1970s. That one is now in a well-known private collection. In its online catalog, the provenance given for the manuscript is simply the name of the dealer from whom it was purchased.

By the time those manuscripts were taken out of Ethiopia, the colonial era was over. International protocols and national laws regulated the export of cultural heritage. Neither of these manuscripts should have adorned a private collection or enriched a dealer. This story illustrates two of the greatest threats to cultural heritage: the desperation that leads people to sell off their own heritage in order to feed their families and the profiteering by those who exploit that misfortune.

Two of the greatest threats to cultural heritage are the desperation that leads people to sell off their own heritage in order to feed their families and the profiteering by those who exploit that misfortune.

Lebanon and Syria

The Ethiopian project inspired another serendipitous chapter in our work. Just after the turn of the millennium, Orthodox Christians in Lebanon asked for our help in dealing with the aftermath of a civil war that had ended about a decade earlier. Collections had been moved, valuable manuscripts had been stolen and held for ransom, and some had simply disappeared. We launched a project in northern Lebanon in April 2003, at the same moment that U.S. ground forces were approaching Baghdad.

As our work in Lebanon expanded, we extended the project to Syria, forming partnerships with several church leaders in Aleppo, as well as in Homs and Damascus. Things were going well, and we even found a partner in Iraq. But then, in 2011, Syria began to unravel as the spirit of the Arab Spring spread across the region. Three years later came the conquest by ISIS of much of northern Iraq, driving tens of thousands of Christians and Yazidis from Mosul and the villages of the Nineveh Plain.

ISIS broadcast videos of its crude but effective demolition of ancient Assyrian and Christian monuments in Iraq, and we watched the destruction of so much in Syria, including historic places like Palmyra. In Turkey, where we had worked with the Armenian community in Istanbul, and more extensively in the Syriac Christian libraries of the southeast, the areas we had visited so many times became no-go zones because of rising tensions between Kurds and Turks. As is often the case for ethnic and religious minorities, the Christians—those who had not already emigrated—were caught in the middle.

The human toll among our friends and colleagues was immense. In 2013, the Syriac Orthodox bishop of Aleppo, Mor Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim, was kidnapped along with his Greek Orthodox counterpart, Metropolitan Boulos Yazigi. They were never heard from again. Mor Gregorios had been an enthusiastic supporter of our work with his community’s manuscripts in Aleppo. Many of those manuscripts had been carried to Aleppo in 1923 as Christians fled the Turkish city of Sanliurfa, known in ancient times as Edessa, the very cradle of Syriac Christianity.

ISIS broadcast videos of its crude but effective demolition of ancient Assyrian and Christian monuments in Iraq, and we watched the destruction of so much in Syria, including historic places like Palmyra.

Qaraqosh, Iraq

In Iraq it would be even worse. Our partner there, Najeeb Michaeel, a Dominican friar, had established a center for digitization of Christian manuscripts in Qaraqosh, an ancient Christian village between Mosul and Erbil. Since 1750, Father Najeeb’s community had been in Mosul, the ancient city of Nineveh where the prophet Jonah preached repentance. The kidnapping and murder of the Chaldean Catholic Archbishop Paul Rahho in 2008 made it too dangerous for clergy to remain in Mosul, and they relocated to Qaraqosh. With our help, his team digitized thousands of Syriac, Arabic and Armenian manuscripts.

Then came the summer of 2014, the summer of ISIS. It did not seem at that time that ISIS was moving east from Mosul into the Nineveh Plain, and Father Najeeb’s village of Qaraqosh was guarded by Kurdish militias as part of the outer ring of defenses of their autonomous region. Nonetheless, Father Najeeb decided to begin to move the manuscripts and archives of the Dominicans to Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. It was a wise move.

On the morning of Aug. 6, the feast of the Transfiguration of Jesus, the Kurdish guards in Qaraqosh retreated from an ISIS advance. Residents of that and the many other villages of the Nineveh Plain had only hours to grab what they could and get to Erbil, travelling 40 miles in the heat of the Iraqi summer. I visited them many times, marveling at how they recreated a kind of village life in the refugee camps.

At Mar Behnam Monastery, some 500 manuscripts were hidden behind a false wall during the two-year occupation of the monastery by ISIS.

As the refugees started over in Erbil, ISIS was demolishing ancient Nimrud with barrel bombs, destroying the artifacts in the Mosul museum with sledgehammers and dynamiting churches. Only after the retreat of ISIS from the Nineveh Plain in 2016 and the final reconquest of Mosul in 2017 did the picture become clear. Major manuscript collections in Mosul had been destroyed, leaving behind only the digital images and a handful of severely damaged volumes. Most collections outside of Mosul, however, had been saved. This was the case at Mar Behnam Monastery, where some 500 manuscripts were hidden behind a false wall during the two-year occupation of the monastery by ISIS. When the monks returned to their wrecked home, they found the manuscripts safe in their hiding place, a still-beating heart in the battered and bruised body of the cloister.

I began this essay with Peter the Venerable for a reason. For a Benedictine monk to partner with a Dominican friar or a Syriac Orthodox bishop to preserve Christian manuscripts is understandable. It might not be as readily apparent why we have become so involved with the digital preservation of manuscripts belonging to Muslim communities in Africa, the Middle East and south Asia.

In 2013, the Palestinian field director for our work with Christian manuscript libraries in the Old City of Jerusalem told me about a recent conversation with a friend about his work preserving manuscripts. The friend belongs to an old and distinguished Muslim family. Fascinated by David’s work, he said, “What about us? We have manuscripts too.” On my next trip to Jerusalem, I met with members of that family and saw their library.

As I learned more about their family’s library and discussed the project with our board, I became convinced that we must work with them. Their Islamic manuscripts and the Syriac Christian manuscripts we had been digitizing at a monastery only a few minutes’ walk from that home belong to a cultural ecosystem that has existed since the arrival of Islam in Palestine in the seventh century. Christians and Muslims have greeted each other in the streets, done business, engaged in religious disputes and have read each other’s books. Like Peter the Venerable, their interest may have been for the sake of persuasion or refutation, but it also led to the sharing of scientific and historical knowledge.

Since the arrival of Islam in Palestine in the seventh century, Christians and Muslims have greeted each other in the streets, done business, engaged in religious disputes and have read each other’s books.

Timbuktu, Mali

This new phase of our work soon led to an even larger involvement with Islamic manuscript heritage from another fabled place: the desert city of Timbuktu in northern Mali. Timbuktu was at one time a center of political power, trade, religion and culture. Located in the Sahel, the transitional zone between the desert to the north and the savanna to the south, the city was the terminus of trans-Saharan, savanna and forest trade routes that brought salt, goods and travelers from North Africa and even beyond, as well as slaves and gold, textiles and other goods from the south. And, of course, there were manuscripts traveling the same pathways.

The recent story of Timbuktu is once again a tale of manuscripts moved and manuscripts hidden. Knowing that something was coming—as did Father Najeeb in Iraq—Dr. Abdel Kader Haidara quietly sent the manuscripts of his own family’s library and those of more than 30 other families up the Niger River to Bamako, the capital of Mali, in case the threats of religious and ethnic rebel groups to capture Timbuktu and purge its culture of supposed “non-Islamic” elements should come to pass.

In June 2012, those threats were realized. Timbuktu was occupied for several months, its shrines to Muslim saints destroyed, its superb music silenced, the tourist trade on which it depended for economic survival extinguished. Early reports suggesting that its manuscripts had been burned proved to be incorrect: Only a few manuscripts left behind as a false trail had been destroyed. All the others were safe, whether moved to Bamako or hidden in Timbuktu.

The recent story of Timbuktu is once again a tale of manuscripts moved and manuscripts hidden.

Why It Matters Here and Now

The intellectual pathways we trace in our preservation efforts reveal the original “internet of things,” the manuscripts that traveled in a merchant’s chest, in a monk’s pocket or in a pilgrim’s pouch across the known world. Their power was in their words, words usually read aloud, in the way of traditional reading. As listeners heard, they heard another person’s voice in real time.

In those manuscripts are stories, reflections on stories, ideas spun from human observation and experience. These manuscripts changed the world because their words were heard. They were taken seriously, seriously enough at times to prompt rebuttal or controversy, admiration or adoption. But they were heard.

We are at great risk of losing the capacity to listen and, therefore, of losing our ability to understand. The opening word of St. Benedict’s Rule is, appropriately, obsculta, or “listen.” Equally endangered are the stores of wisdom contained in the manuscripts of the world, targeted by those fearful of difference or threatened by imaginations broader than their own. The wisdom contained in them is eroded by the forgetting that besets a diaspora community severed from its roots, resettled in a strange place and often undergoing the slow but inexorable loss of its language and distinctive ways.

The intellectual pathways we trace in our preservation efforts reveal the original “internet of things,” the manuscripts that traveled in a merchant’s chest, in a monk’s pocket or in a pilgrim’s pouch across the known world.

What happens when we fail to listen, or forget the wisdom of the ancestors? No institution, however venerable, is immune to the consequences of forgetting its ideals or ignoring the voices of its critics. Peter the Venerable was abbot of Cluny at its zenith; six centuries later, the monastery and its great church were plundered and its library burned. At one time Cluny had represented a great reform of Benedictine life. At its end, it represented everything the poor had come to hate about the concentration of wealth and power in the church and the aristocracy.

And yet, Benedictines are still here. As the motto of the bombed and rebuilt abbey of Monte Cassino proclaims, Succisa virescit: “Cut it back, and it flourishes.” Humbled by the Reformation, the French Revolution and its aftermath, we had to rethink what it means to be monks in the modern world. We are still working on that.

What is true of my small part of the human community is also true of nations when they forget to listen, or simply give up trying. Our fragile planet has never been so threatened, nor the human beings who inhabit it so divided. The terrain for rational discourse has shrunk to a narrow strip between camps defined and limited by their political views, religious beliefs, race or ethnic identity, beset by anxiety that easily becomes fear and then violence. In such times as these, we must dig deeply into our respective stores of wisdom and offer whatever we find for the sake of mutual understanding, the only possible basis for reconciliation and for the resolve to move forward for the common good.

What is true of my small part of the human community is also true of nations when they forget to listen, or simply give up trying. Our fragile planet has never been so threatened.

Our Common Enemy

We are today facing a new temptation to ostracize and demean, this time because of the sincerely held religious beliefs of our Muslim sisters and brothers. This is not simply a divisive geopolitical issue but an urgent local problem, even in my adopted state of Minnesota with its immigrant Somali and other Muslim communities. As medieval Christian scholars of Arabic manuscripts came to understand, their enemy was not Islam, however deep their theological differences. The common enemy was—and remains—the fanaticism and ignorance that make understanding impossible.

My roots in an ancient monastic tradition give me a certain perspective, and dare I say, a certain confidence and hope when considering the work that lies before us. I recall the story told long ago by a young African man, confused and emotionally tormented, who heard the voice of a child chanting, Tolle, lege; tolle, lege. “Pick it up and read it. Pick it up and read it.” He picked up the book at his side, and he read it, as if for the first time. His name was Augustine, and in time he would become the finest writer of Western Christianity. But first he had to pick up the book—of course it was a manuscript—and read. May we do the same.