The grim anniversaries this week of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might bring to mind for older Americans a relic of another era: the fallout shelter. Once a national craze, the fallout shelter has all but disappeared from our consciousness. Why? It’s a long story, with an America connection.

As the Cold War seemed close to going hot in the early 1960s, the question of how to protect the civilian population from a Soviet nuclear attack was a commonly debated one. (And no, getting under your desk at school wasn’t going to work.) While politicians debated the cost and effectiveness of public fallout shelters, a huge industry emerged providing private shelters to American homeowners.

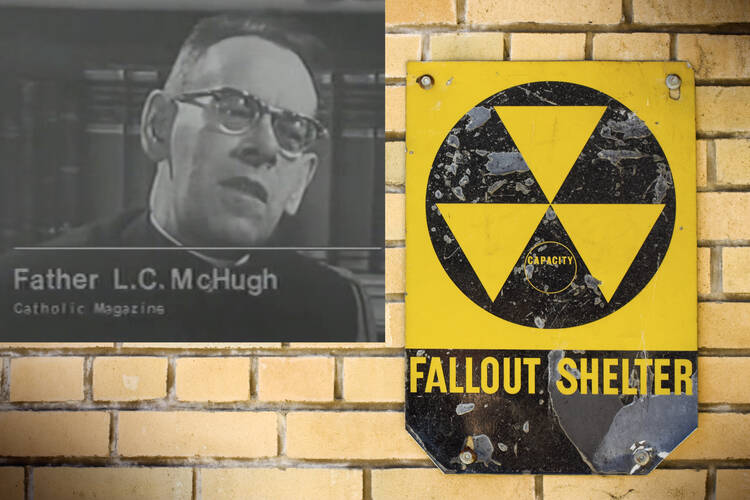

Robert F. Kennedy in 1961: “There’s no problem here—we can just station Father McHugh with a machine gun at every shelter.”

In August 1961, Time magazine ran a story on the phenomenon of Americans stockpiling weapons in such shelters to protect themselves against less well-prepared neighbors who might seek entrance when the bombs began to fall: “Gun Thy Neighbor?” The article concluded with reactions from clergy of different Christian denominations, almost all of whom expressed an uneasiness with the idea of barring others from one’s own family shelter, with one minister declaring that “if someone wanted to use the shelter, then you yourself should get out and let him use it. That’s not what would happen, but that’s the strict Christian application.”

Enter L. C. McHugh, S.J., an associate editor at America and a former ethics professor from Georgetown University. McHugh took objection to the quote above in an essay for America on Sept. 31, 1961, titled “Ethics at the Shelter Doorway.”

“I cannot accept that statement as it stands,” he wrote. “It argues that we must love our neighbor, not as ourselves, but more than ourselves.” It was important, McHugh noted, to remember and apply traditional Christian principles of self-defense to the question of “gunning one’s neighbor at the shelter door.” Those principles, he argued, made it clear that every shelter owner had a right to defend his or her shelter for the use of family and friends—and that there was no moral prohibition against using deadly force to do so.

McHugh continued in blunt terms. “If a man builds a shelter for his family, then it is the family that has the first right to use it. The right becomes empty if a misguided charity prompts a pitying householder to crowd his haven to the hatch in the hour of peril; for this conduct makes sure that no one will survive,” he wrote. “And I consider it the height of nonsense to say that the Christian ethic demands or even permits a man to thrust his family into the rain of fallout when unsheltered neighbors plead for entrance.”

It was important, McHugh noted, to remember and apply traditional Christian principles of self-defense to the question of “gunning one’s neighbor at the shelter door.”

Further, he wrote, “If you are already secured in your shelter and others try to break in, they may be treated as unjust aggressors and repelled with whatever means will effectively deter their assault. If others steal your family shelter space before you get there, you may also use whatever means will recover your sanctuary intact.”

Was McHugh being entirely serious, or was the whole thing a kind of Swiftian modest proposal, a satire designed to horrify those who were up until then supporting fallout shelters? In truth, his author bio for the article stated that “Our guess is that Fr. McHugh would be the first to step aside from his own shelter door, yielding space to his neighbor.”

And indeed, the article did not bolster the fallout shelter industry, but tolled its death knell: A bit of a media frenzy followed its publication, with everyone from The New York Times to the national wire services reporting on it and reactions coming from all quarters, most of them condemnatory. The repugnance many readers felt toward McHugh’s argument seemed to trigger a national reckoning with the unspoken assumptions of fallout shelters and their moral significance.

McHugh doubled down two months after his initial article, writing “More on the Shelter Question” for the Nov. 25, 1961 issue of America and asking “a series of rather excruciating questions” about the morality of fallout shelters. While admitting his analyses “took a somewhat technical approach to a crisis of conscience,” he nevertheless laid out some of the moral dilemmas both citizens and governments could face in the event of a nuclear war.

Letter writers to America wondered if McHugh had lost his moral compass. The preeminent Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr accused him of “justifying murder.” Writing in Time, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, Bishop Angus Dun, called McHugh’s position “utterly immoral.” Even Billy Graham weighed in eventually, saying he was against the construction of private fallout shelters.

The private shelter-building craze died out over the next few years, with many Americans seeming to punt the project to the federal government or to prefer not thinking about the aftermath of the unthinkable.

McHugh’s article even reached the desks of those at the highest levels of government. In Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s A Thousand Days, he recounts a discussion of public fallout shelters among Kennedy Administration officials at Hyannis Port in 1961 that included a sour comment from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy: “There’s no problem here—we can just station Father McHugh with a machine gun at every shelter.”

McHugh’s article gained public mention again a few years later when George G. Kirstein, the publisher of The Nation from 1955 to 1965, penned an article for The Progressive in June 1963 on “The Myths of the Small Magazine.” Kirstein argued that the essay, though perhaps written with McHugh’s “tongue pretty firmly tucked in his cheek,” had proved the value of smaller journals of opinion which were sometimes maligned for only reaching those who already agreed with their views—that “they carry coals to Newcastle.” But McHugh’s extraordinary thesis, Kirstein wrote, had “aroused a storm of heated argument across the country.”

Kirstein concluded thus:

America is an intellectual, political, and cultural weekly, edited by Jesuits and read for the most part by Catholic intellectuals. Yet Father McHugh’s article sparked debate among those of every shading of religious faith. Was America reaching only an audience that already agreed with it? Carrying coals to Newcastle? Some size city, that Newcastle!

Was McHugh being entirely serious, or was the whole thing a kind of Swiftian modest proposal?

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Why Some Look Up to Planets and Heroes,” by Thomas Merton. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, this summer the Catholic Book Club will be reading and discussing Mary Doria Russell’s novel, The Sparrow. Click here for more information or to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

Vatican II’s secret priest-journalist: The story of Xavier Rynne

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

The mystery of Thomas Merton’s death—and the witness of America magazine’s poetry editor

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Theophilus Lewis brought the Harlem Renaissance to the pages of America

Happy reading!

James T. Keane