In the beginning was the spoken word—the Bible we’ve inherited derives in large part from a mix of oral transmission and oral tradition. So it should hardly be surprising to find that its text can feel at home in the theater, as it did in George Drance, S.J.’s “*mark,” a solo staging of the Gospel of Mark at LaMaMa in 2014, and as it does now in Ken Jennings’s “The Gospel of John,” now onstage at New York City’s Sheen Center through Dec. 29.

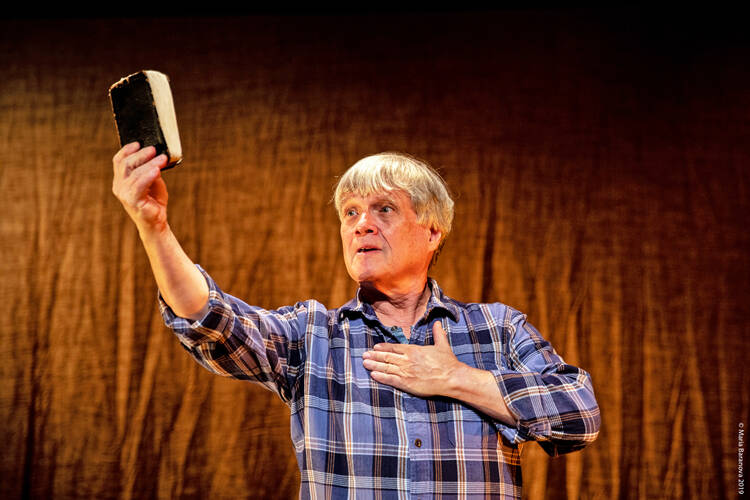

Dressed in a plain flannel shirt and jeans, Jennings—best known for originating the role of Toby 40 years ago in the original Broadway production of “Sweeney Todd”—roves a raked wooden stage and delivers more or less the entirety of the Johannine Gospel, in a straightforward, often spellbinding staging by the director John Pietrowski. And while your mileage will vary in terms of theatrical electricity, particularly given this Gospel’s denser passages, there is no gainsaying the power of hearing Scripture spoken aloud from start to finish. Most of us hear these texts piecemeal from a pulpit, doled out according to the lectionary. To witness them live, without interruption, is a unique blessing.

There is no gainsaying the power of hearing Scripture spoken aloud from start to finish.

It’s especially remarkable that Jennings can strike sparks off John’s Gospel, which interweaves some indelible signature scenes—the wedding at Cana, the resurrection of Lazarus, doubting Thomas—with an ungainly mass of heavily theological speechifying. John’s approach to the tale of Jesus’s life, ministry and Passion was less that of a bard or poet than of a kind of exegete or pundit, loading interpretation onto narrative, and sometimes forgoing storytelling altogether in favor of sermonizing. This is true of John’s stunning, Genesis-like prologue and of many moments after, especially what I think of as his long goodbye at the Last Supper, in which he spends five chapters alternately comforting and challenging his disciples, some of whom must surely have nodded off at some point. It seems like no coincidence that while the other Gospels have Jesus frequently using some version of the phrase, “Truly, I say to you,” John instead doubles down, having his Jesus say, “Truly, truly, I say to you.”

That extra emphasis is a whole personality sketch in itself, and Jennings—alternately stern and gracious, stentorian and plain-spoken—effectively embodies John’s almost pleading insistence and his deep, heartfelt passion. This guy really, really means what he says and wants you to hear it.

But if John was an inveterate sermonizer, he was also a brilliant phrasemaker.

But if John was an inveterate sermonizer, he was also a brilliant phrasemaker, giving us talismanic gems that need no introduction: “Greater love has no man than this,” “For God so loved the world,” “I am the bread of life,” “I was blind and now I can see,” “The truth shall set you free,” “My kingdom is not of this world,” “In my father’s house are many rooms,” not to mention the withering comic put-down, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” For my money, though, John’s signal contribution to the portrait of Christ is not a quote but a two-word stage direction, from the story of Lazarus’s death: “Jesus wept.” It should not be overlooked that this most theological of Gospels, which noticeably skips the Nativity and other such earthly matters, at key points also takes the time to humanize the divine figure at its center. After all, what does Jesus do before he launches into that interminable farewell monologue? He washes his disciples’ feet, an astonishing gesture as pregnant with metaphor as it is teeming with tactile sensation.

“I have spoken to you in figures,” Jesus says near the end of that long valedictory address, “but the hour is coming when I will tell you plainly of the Father.” This “Gospel of John” gives the evangelist’s windy, heady symbolism its due, but it is in the plain-speaking scenes of contention and communion among its human figures that the show most comes to life. Jennings, for example, occasionally changes third person to first, speaking of the disciples as “we” rather than “they.”

Finally, after a seaside fish breakfast as lovingly described as any post-Resurrection appearance, Jennings closes by tapping his chest proudly on the words, “This is the disciple who bears witness to these things.” In “The Gospel of John” we have a fine exemplar of the unique witness theater can bear.