The highest tribute you could make to the sprawling, blockbuster exhibition “David Bowie is” (now at the Brooklyn Museum through July 15, the culmination of a five-year global tour) is that it is a bit like a great David Bowie album itself: a seductive, disorienting collection of alternately gritty and glittering artifacts that are much more than the sum of their parts, and that invite puzzlement as much as pleasure.

A blockbuster exhibition profiles one of the 20th century's great bridge figures.

Like a good rock album, too, it sticks in your head and merits revisiting. I have been to the exhibition twice and may go again. There are just so many details to take in, from nearly every phase of this peripatetic musician’s extraordinary five-decade career. Curated by Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh, “David Bowie is” begins chronologically, with David Robert Jones’s lower-middle-class upbringing in postwar London; touches on his autodidact’s schooling in the demimonde and the avant-garde; and hurtles forward through the psychedelic 1960s to his first hit, “Space Oddity,” a would-be novelty song with remarkable staying power, which created a template for his work to come: Bowie as spaceman, the alienated alien tuned into otherworldly, even forbidden frequencies.

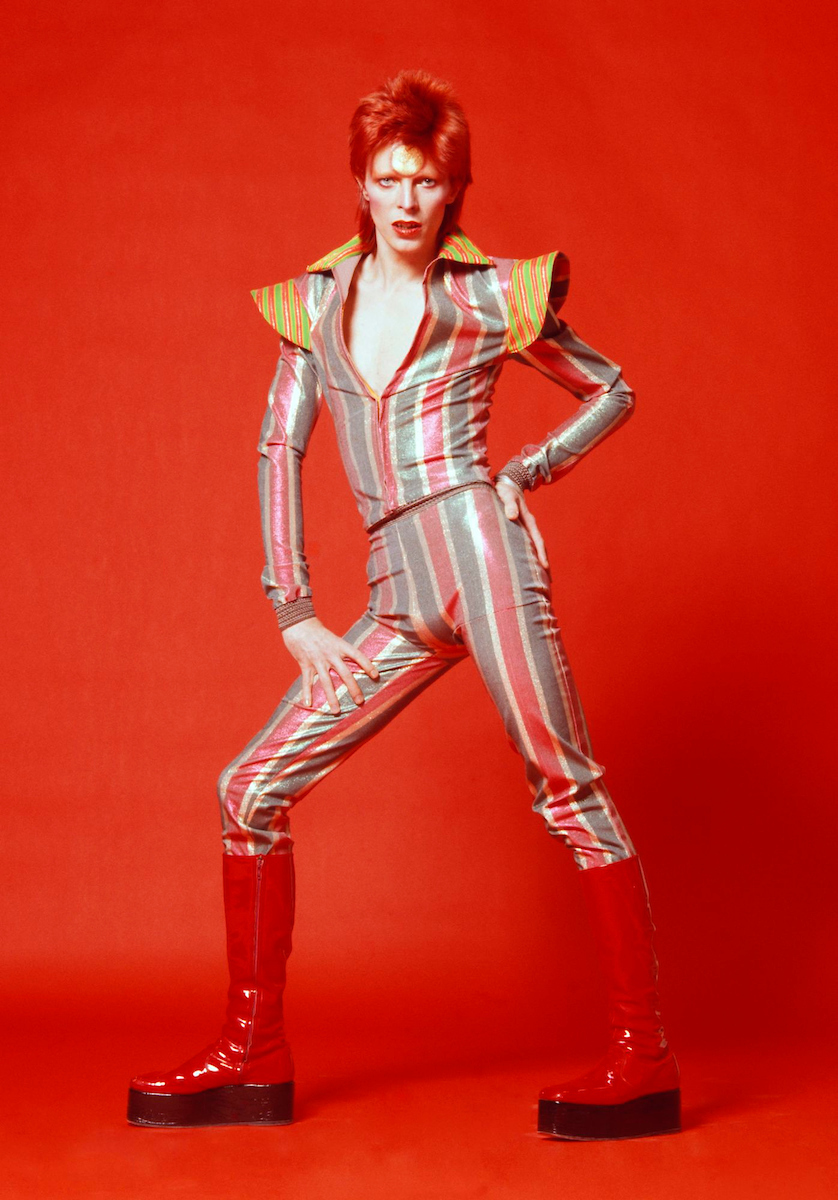

From there, the exhibition also blasts off into orbit, leaving chronology behind and rocketing us among the various Bowie dispensations, from his 1970s heyday right up to his final album, “Blackstar,” released days before his death in 2016. Set models and notes for a planned film realization of the Orwellian hellscape described in his “Diamond Dogs” album sit beside the Expressionist-inspired plastic dress/sculpture he perched inside for a memorable “Saturday Night Live” appearance. Nearby is a demonstration of his “Verbasizer,” a random-lyric-generating computer program, modeled after William S. Burroughs’s “cut-up” technique, that Bowie helped cook up in the 1990s, and which he describes as functioning “like a technological dream.” Album art sits in cases near lyric notebooks, and costumes from his many guises and eras are displayed throughout, from colorful suits and jackets by Freddie Burretti to the signature leotards and kimonos of Kansai Yamamoto.

It would be a mistake to look at Bowie’s work as merely an act, a put-on.

If all that isn’t sensory overload enough, there are screens galore, broadcasting music videos, snippets of interviews, and excerpts from his films and plays as an actor. (The spectacle reminded me of the dapper alien Bowie played in the film “The Man Who Fell to Earth,” who tries to give himself a crash course in Earth culture by assembling a wall of TVs, all tuned to different stations.) To hear the sound for each, we are issued a headset designed to sense when we are in front of a given object and to play us the corresponding audio track; both times I went, my headset lagged behind or jumped ahead to play sounds from another location before finally locking in. In one large room of the exhibition, a mix of wildly varying Bowie songs seems to stop and start and overlap, depending which direction you go, as if we are human antennae picking up various radio stations. I can’t imagine that this sense of dislocation is entirely an accident.

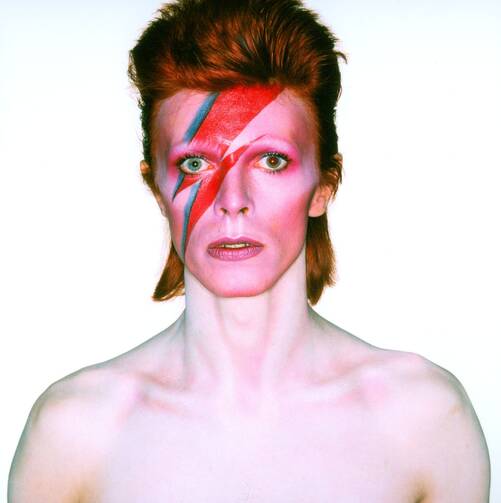

For what Bowie’s career as a rock legend and style icon signified above all was a radical, shape-shifting indeterminacy. His playing with gender identity and his multiple “characters”—Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke—were signs that he was treating rock as theater. I do not just mean that he put on elaborate stage shows, which he did, but that he very seldom revealed “himself” in his music, and never relied on a sense of rootsy authenticity to connect with fans. “I act the songs rather than sing them,” he once told Dinah Shore on her TV talk show.

What also emerges from the exhibition is that while Bowie wasn’t always clear on what his next move would be—there is a room dedicated to his confounding, then clarifying late ’70s Berlin period, which produced some of his best work—he was unquestionably the impresario of his vision, director as much as actor. The exhibition alludes throughout to some of his inspirations in 20th-century theater and cabaret, from Bertolt Brecht to Eartha Kitt. I found his description of having seen the late ’60s stage musical “Cabaret” most telling: His takeaway is less the show’s depiction of decadent Weimar Germany than the production’s blinding white lighting.

If this all sounds a bit rarefied, it can be. There is a certain hagiographic cast to the explanatory texts, completing sentences begun by the exhibition title “David Bowie is” with phrases like “a success in New York” or “making a scene” or “forever and ever.” The focus is almost entirely on Bowie’s work, not his life; apart from the aforementioned Berlin room, there are precious few allusions to his drug problems or personal torment. In one room that booms with concert footage, displayed primly alongside other touring ephemera (setlists, lighting plots) is a tiny cocaine spoon.

But it would be a mistake to look at Bowie’s work as merely an act, a put-on, or to class him with the many rock star burnouts. He was one of the last century’s great bridge figures, linking rock to the avant-garde, Dada to New Wave. And he was never more himself than when he was in character. What comes through his best work is a subversive confrontation with the instability of identity. Are we more than the masks we wear? Can we escape them—or are we just putting on another mask? Bowie entertains, yes, but his best work also makes us look deeper.

At the entrance of the exhibit is a notebook dating from the 1999 album “hours…,” and it crystallizes Bowie’s mission statement: “All art is unstable. Its meaning is not necessarily that implied by the author. There is no authoritative voice. There are only multiple readings.” And multiple replays.

It’s also no mystery that David Bowie regularly engaged in sexual activity with minors. Does the exhibit address this? I doubt it. Mr. Weinert-Kendra makes no mention of it.

I guess it’s still true that what matters is not who is being abused but who is doing the abusing.

Please, cite one credible source. If you can't, please shut up.

Bowie did speak of a theme of alienation in his work, but that lessened with age. While his path was long and winding, he was a seeker whose journey concluded in a 24 year happy marriage with Iman. He spoke openly of the wonderful impact of sobriety in his life, with the help of AA, and loved his 2 beautiful children immensely. He retired from touring in 2004 so he would not have to be away from his young daughter. While many tell tales of his wilder past (sometimes exaggerated), it is an injustice to ignore the huge strides he made in his personal integration.