The documentary “Arthur Miller: Writer” (debuting March 19 on HBO) takes its title from an interview with the late American playwright in which he offers these words as his ideal epitaph—nothing more, nothing less. But the title of this tender if incomplete portrait by filmmaker Rebecca Miller, the writer’s daughter, ought to be “Arthur Miller: Father.” In the vein of the recent hagiographic Joan Didion documentary, “The Center Will Not Hold,” made by her nephew, Griffin Dunne, Rebecca Miller’s film is explicitly personal, a mix of home movies, interviews and a smattering of archival footage, with narration by Ms. Miller herself.

Those seeking a deep dive into the playwright’s work or creative process should look elsewhere. But those curious about the personal forces that shaped Arthur Miller, and about how he imperfectly reconciled his ambitions with his domestic and emotional life, may reckon with the uncomfortable feeling that the man who created Willy Loman, the faded dreamer of his iconic 1949 play, “Death of a Salesman,” lived out a happier, more self-aware version of that needy, optimistic character’s pathetic twilight. He retreated to the comfort of his family hearth, leaned on the support of a strong wife and continued to idealistically ply his trade to the end—even as the professional world that once elevated and honored him increasingly rejected or dismissed him, and he began to doubt the value of his efforts and, by implication, his manhood.

Rebecca Miller has made a film that pays complicated tribute to a complex man.

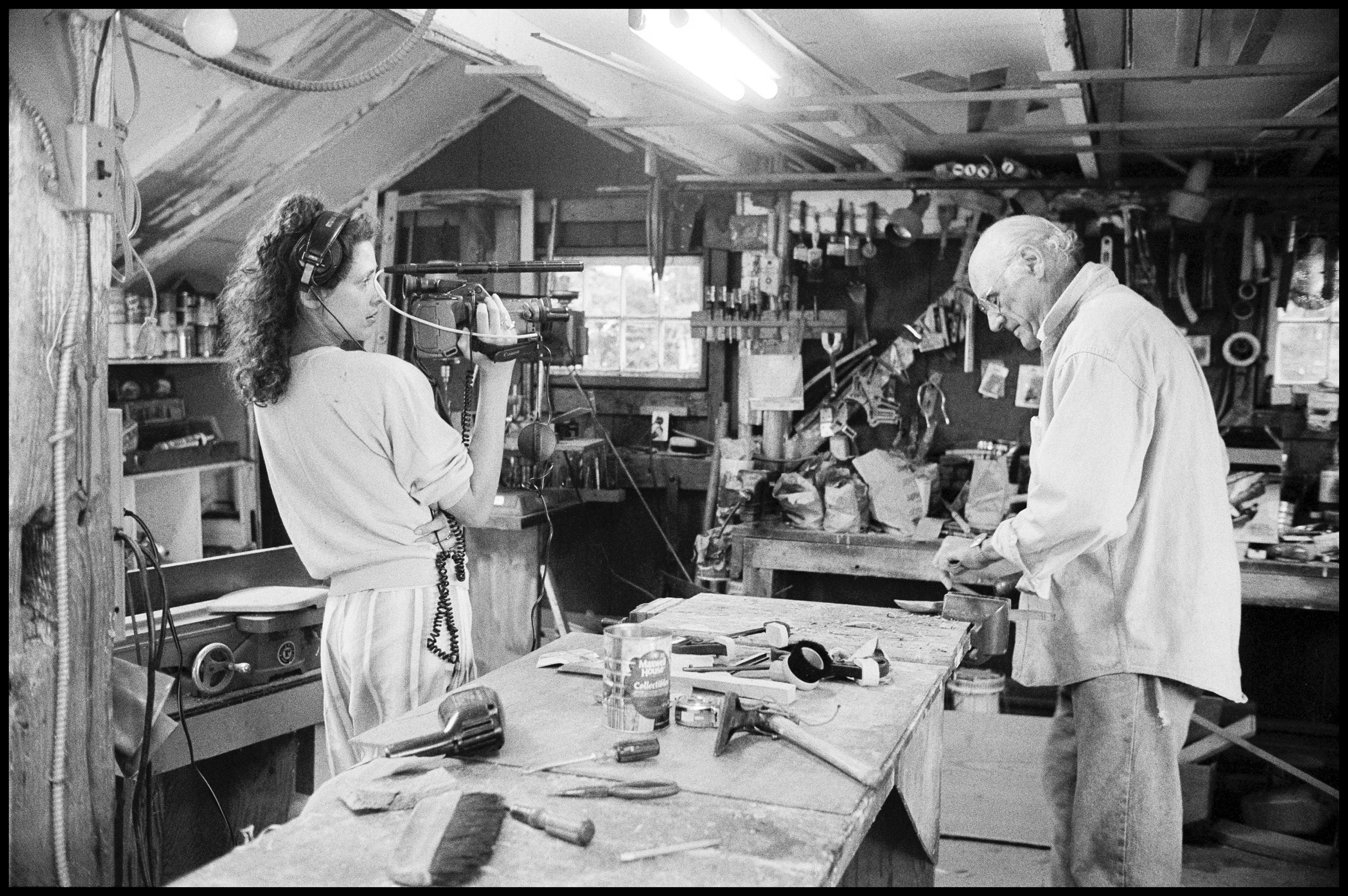

Indeed, if there is an underlying drama in this otherwise placid-seeming film, full of kitchen-table chatter and endless footage of Miller puttering about his woodshop and garden, it is his daughter’s delicate exorcism of the demons of a man she knew as “very funny, cuddly, jokey” but who had lived a few contentious lifetimes before she was born. While Mr. Miller admits in interviews with her that he tends to flee from conflict in real life, choosing instead to put that pain into his plays, Ms. Miller gives herself the thankless task of delving into his first two marriages (she is the child of his third, to photographer Inge Morath) and addressing the awkward biographical fact that emerged publicly only after her parents’ deaths in the early 2000s: She has a brother, Daniel, who was born with Down syndrome and quietly institutionalized, essentially erased from the Miller family portrait. (He is not shown, out of respect for his privacy, but we are assured in a voiceover that Ms. Miller has developed a close relationship with him.)

She may not have her father’s ruthless truth-seeking instinct, but Rebecca Miller has made a film that pays fittingly complicated tribute to a complex man, who can say to her, with a mix of rue and candor, “I enjoyed being a father; I enjoyed also escaping being a father.”

This ambivalence may stem from the fact that, for all of Mr. Miller’s relentless focus on the fraught, competitive relationships of fathers to sons, he was clearly his mother’s son. It’s true that watching his implacable businessman father, Izzie, disintegrate after the Great Depression was searingly formative. But he clearly saw this tragedy in part through the disappointed eyes of his mother, Gussie, whom he more closely resembled physically, and whose literacy and gumption powerfully mapped her son’s horizons. His brother, Kermit, recalls her as a “strong personality” prone to dancing on the table at family celebrations. Did she keep a kosher house, Rebecca Miller asks her father. “Yes, until she made bacon. She loved bacon.”

The pattern of seeking love and support from strong women continued into his first marriage, to Mary Slattery, with whom he had two children, Robert and Jane, and at whose side he first made his way as a writer with a failed play, a novel, and then the triumphs “All My Sons” and “Death of a Salesman.” His final marriage, to the vigorous, peppery Morath, seems to have been a happy and steady one.

“There’s no explaining a person like that,” Miller says of Marilyn Monroe.

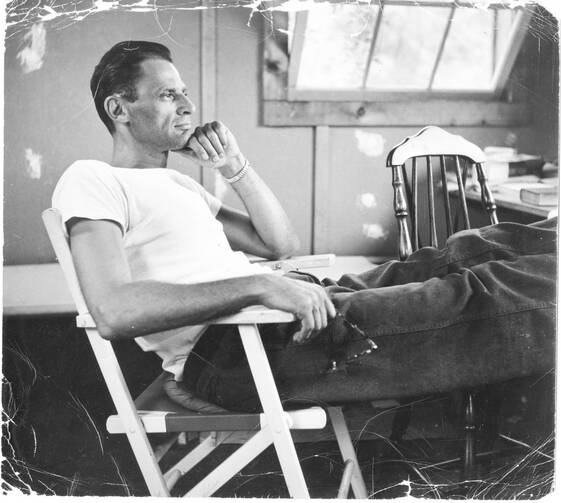

It was his second marriage, to the brilliant but brittle Marilyn Monroe, that was an anomaly, as he took on the role of caretaker to the damaged star—a role to which he was particularly ill-suited. You can see his discomfort in the vintage footage from the 1950s, in which he and Monroe dart quickly, almost sheepishly, through the glare of the public eye. And when he talks about Monroe and her suicide with his daughter, Mr. Miller has a grim, bewildered, almost out-of-body look. “There’s no explaining a person like that,” he says at one point, pausing for a long moment of uncomprehending horror that is more eloquent in its helplessness than the self-justifying play he wrote about their relationship in 1964, “After the Fall.”

Though the film touches on the fortunes of his theater career, including a bittersweet glance at his poorly received final play, “Mr. Peters’ Connections,” it is seen and explained exclusively through his own perspective. Apart from mentions of his collaboration with Elia Kazan, you would never suspect from this film that Mr. Miller’s plays had directors. Mike Nichols, who directed a definitive “Salesman” revival in 2012, is on hand as a fan and friend, not a colleague. And Tony Kushner, one of few living dramatists who could be seen as among Miller’s heirs, provides admiring critical commentary on the plays, sparking especially to the belated appearance of Yiddishkeit in the character of a junk dealer in Miller’s 1968 play “The Price.”

Indeed, Mr. Miller’s Jewishness is mostly brushed past here, as it was through most of his life; as he puts it, he inherited from his father “the attitude of being an American more than a Jew.” At one point Ms. Miller asks him to consider his work’s resonance with the Kabbalah, to which he responds, “I think it’s more that the process of approaching the unwritten, unspoken, the unspeakable—the closer you get to that, the more life the work has.” This is the voice of a man who was ever pragmatic in the face of mystery, who famously could not complete “Salesman” until he had built, with his own hands, the small cabin in which he would write it.

This points to a final contradiction of Miller’s life, and a very American one. If a key insight of his work is that we are shaped by impersonal social and economic forces as much as by our own will or self-determination, he clearly didn’t get the memo himself. Near the end of his life, he talks about his daily writing practice, in a bucolic homestead he has forged deep in the woods of Roxbury, Conn. He says of the challenges and setbacks he’s faced, “I never blame other people, because it’s not true.” Individual agency or collective responsibility? Much of our politics is built upon that beam-splitting dichotomy. So is our drama.

I just re-read "Salesman" after the first time 40 years ago. I was under the impression - probably because of what my teacher explained - that the play was about how we go into life with high expectations, but a mean, capitalistic culture can end up destroying our dreams. On the second read, I saw Willie as a dreamer who really never made the effort to learn a trade but relied on people liking him as his means to becoming successful. Biff, the anti-Math, failure who squandered a sports scholarship was taking the same doomed path.

So maybe in "Salesman" Arthur Miller did not reveal a contradiction between his stories and how he lived his life. Mr. Miller succeeded through learning a valuable skill and working hard, while Willie Loman wallowed in the failure of his own making.