Like the film directors of the 1960s and ’70s or the TV showrunners of today, great playwrights are brand names whose voices we follow from project to project. But the number of American dramatists who have the cachet of a Martin Scorsese or a Shonda Rhimes, say, is vanishingly small, particularly if you limit it to American playwrights who have been at it in the last few decades: David Mamet, August Wilson, Tony Kushner, Suzan-Lori Parks.

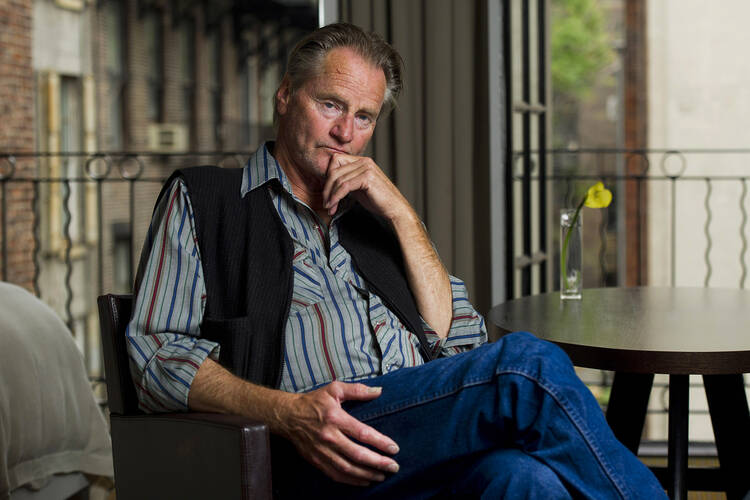

In a class by himself was Sam Shepard, who died on Sunday at age 73. Shepard was unique not only for his signature masterworks—“True West,” “Buried Child” and “Fool for Love” among them—and not only because he cut a lean, memorable figure as an actor in such films as “The Right Stuff” and “Crimes of the Heart” or (my favorite) the weird and woolly “Resurrection.” He was distinctive in that the image he cultivated, of a cowboy Beat poet with a face chiseled as if for Mt. Rushmore, matched his playwriting voice so well. He seldom appeared in his own work, but he did not need to: He and his plays resembled each other so much. Both the man and his work were oddly and jaggedly beautiful, and both embodied and interrogated the individualist mythos of the American West.

Not that there is any one kind of Shepard play. His career had distinct phases, from the drug-addled experiments of his earliest work—some of which he claimed not to remember writing—to the rich middle period that garnered him acclaim and a Pulitzer (for 1979’s searing “Buried Child”). But what unites a quasi-hip-hop musical like “Tooth of Crime” with the domestic realism of “True West,” say, is their relentless focus on the competitive drive of men to define themselves, to make their mark on the world or at least on each other (or on the women and children in their lives).

While Shepard's plays would absorb different rhythms and influences, their essence and voice were unmistakably his—our—own.

This focus on the male psyche should not be mistaken for mere machismo or misogyny. Shepard’s rock-star charisma may have spawned a thousand young bro playwrights, eager to smash conventions and make theater feel more like rock ’n’ roll. But to think of Shepard himself as a men’s movement bard would be a category error along the lines of mistaking Samuel Beckett for a Christian apologist or Edward Albee for a marriage counselor. The subject matter that obsesses a writer is usually the thing they know best, hate most or understand the least—or a tangled mix of all of the above. Shepard, raised in California farm country by an alcoholic Air Force veteran and a Midwestern teacher, had both the high-lonesome landscape of the American West and the middle-class domestic spaces in which we try to contain it etched into his soul. And while his plays would absorb different rhythms and influences, particularly after his time in Greenwich Village’s Off Off Broadway scene in the 1960s, their essence and voice were unmistakably his—our—own.

My own experience with his work was uneven: Some years ago I was the piano player in a Los Angeles production of his early “Suicide in B-Flat,” a series of monologues that come off more like an open-mic poetry slam than a proper play. And I have seen more than my share of half-baked stagings of “Fool for Love” (including the so-so 2015 revival on Broadway). But I was also privileged to catch the legendary 2000 Broadway production of “True West” with Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C. Reilly, and an especially fine 2001 production of “Buried Child” by the L.A. company A Noise Within.

It is hardly original to point out the singular greatness of that capacious, harrowing, sneakily funny play, but here goes. “Buried Child” is the American family drama to end all American family dramas, but it is even bigger than that. Set on a dilapidated Midwestern farm that evokes both a Beckettian heath and a Greek battlefield, it is finally something altogether new and indelible: an American tragedy for the broken-down, de-mythologized country we actually live in, not the one we idealize. In my book, that puts Shepard into the vicinity of prophet—not the see-the-future kind but the show-us-who-we-really-are kind.

“You’ll probably wind up on the same desert sooner or later,” says a character in “True West.” Would a cowboy Jeremiah put it any differently?

Correction, Aug. 2: This essay originally stated that Sam Shepard never appeared in his own work. He appeared in one play and the film version of "Fool for Love."

Wow. Good review. Now you have me searching out Sam Shephard plays for a closer look.