Jesuit Father Chris Collins headed down to St. Louis University’s law school. He heard that a verdict would be passed down on Sept. 15 in the murder trial of Jason Stockley, the white police officer who killed Anthony Lamar Smith, a 24-year-old black man, in 2011.

The trial was a contentious one: Mr. Stockley had been charged with premeditated murder after being recorded saying he was “going to kill this mother f*****” as he chased Mr. Smith’s car through north St. Louis. The prosecution also argued that Mr. Stockley had planted the gun that was recovered from Mr. Smith’s car: DNA experts found Mr. Stockley’s DNA on the gun but not Mr. Smith’s.

Despite this evidence, Mr. Stockley was acquitted, and protesters immediately began demonstrating on the street between the courthouse and the Jesuit law school.

“No matter how the verdict went, we knew there was going to be demonstrations,” Father Collins told America. He knew that Catholic clergy were not often visible at protests and wanted to be there as “a pastoral presence.”

On the sidewalk outside the law school, Father Collins ran into a minister he knew, and some other clergy members from various denominations gathered around. They began to pray together, and as they prayed, someone pulled the group out into the street.

“She would not let go of me, the white, Catholic priest there."

Father Collins said one of the ministers who started the prayer, a black woman whose name he could not remember, held onto him tightly. “She would not let go of me, the white, Catholic priest there,” Father Collins said. “That was potent for me.... Somehow that seemed even tangibly significant.”

This is significant because in St. Louis the African-American and white communities remain starkly divided. Demographic maps of the city show what has been dubbed “the Delmar Divide”: Black St. Louisans largely live north of Delmar Boulevard, and white St. Louisans largely live south of it.

Beyond simply crossing that physical divide, however, when Father Collins supported the minister, he represented what St. Louis’ white Catholics have historically done best in the struggle for racial justice: support and work with their fellow black Christians.

Pioneering Integration

In February 1944, St. Louis was a legally segregated town. Black and white children went to different schools, and the push for white employers like Southwestern Bell to hire African-Americans was just beginning to gain traction.

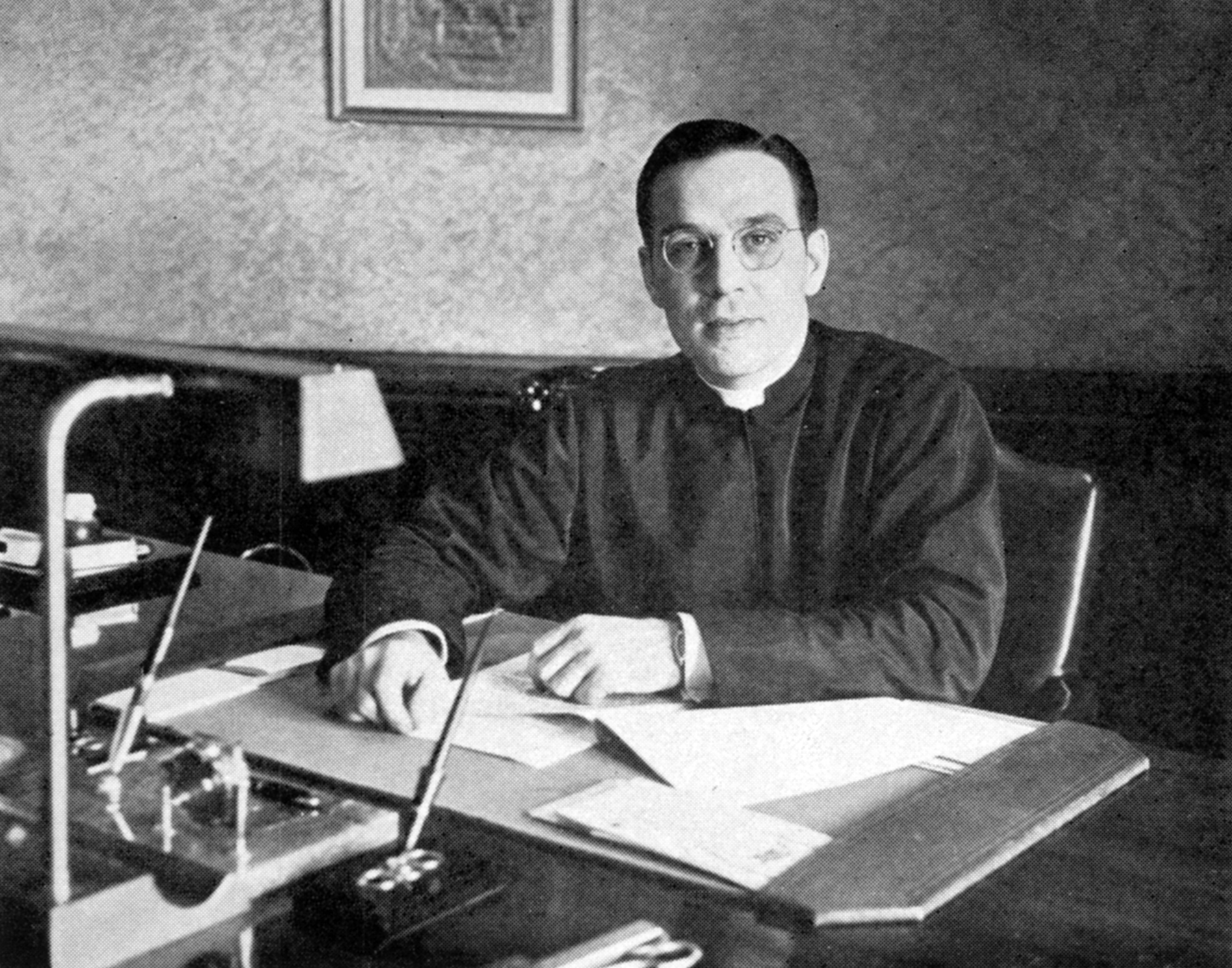

St. Louis University remained segregated. The school’s president, Father Patrick Holloran, and Archbishop (later Cardinal) John J. Glennon were staunchly opposed to integration.

One of the Jesuits at the university, Father Claude Heithaus, saw the university’s segregation as hypocritical and unjust. When he found out he was scheduled to celebrate the 8:45 a.m. student Mass in St. Francis Xavier College Church on Feb. 11, 1944, Father Heithaus drafted a fiery homily denouncing racial prejudice and calling for the university to integrate.

“It is a surprising and rather bewildering fact that in what concerns justice for the Negro, the Mohammedans [Muslims] and the atheists are more Christ-like than many Christians,” the sermon begins. “The followers of Mohammed and Lenin make no distinction of color; but to some followers of Christ, the color of a man’s skin makes all the difference in the world.”

Father Heithaus drew contrasts between Pope Pius XII’s approval of black bishops and his parishioners’ disapproval of a black organist in the church, and between God’s joy when anyone of any race receives Communion and his community’s disdain at kneeling next to an African-American at the Communion rail.

Father Heithaus continued: “St. Louis University admits Protestants and Jews, Mormons and Mohammedans, Buddhists and Brahmins, pagans and atheists, without even looking at their complexions. Do you want us to slam our doors in the face of Catholics because their complexion happens to be brown or black?”

Father Heithaus called the students to stand and make an act of reparation for racism, and a news report from that day says “even the pews stood up.” The students apologized “for all the wrongs that white men have done to [God’s] Colored children” and “resolved never again to have any part in them, and to do everything in [their] power to prevent them.”

Archbishop Glennon reprimanded Father Heithaus for his homily, and Father Holloran forbade him from speaking about race publicly. Still, just months after Father Heithaus delivered his homily, the university became the first historically white college in a former slave state to admit students of color.

Two years later, in 1947, Archbishop (later Cardinal) Joseph E. Ritter announced he would integrate all the Catholic schools in the archdiocese, a cause which Father Heithaus had quietly championed after being censored. When some white Catholics in the diocese appealed to stop the integration, Archbishop Ritter issued a letter to be read aloud at every Mass in the diocese, threatening to excommunicate any Catholic who opposed him. The schools integrated that year, eight years before the nation’s public schools would integrate following the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision.

St. Louis sends sisters to Selma

Father Collins, the Jesuit who prayed in the streets after the Stockley verdict was announced, said an African-American minister recently told him that the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 would not have been nearly as effective in drawing attention to voter discrimination in Alabama if it were not for the presence of Catholic nuns.

Fr. Chris Collins was quick to respond when the verdict came out. Pls. join us in praying for peace & healing. https://t.co/JHMMapGFgDpic.twitter.com/iYlbOyr0vZ

— Jesuits UCS (@JesuitsUCS) September 15, 2017

Sister Anne Christopher, then a Sister of Loretto living in St. Louis’ inner city, was appalled by the violence she had seen in the news coverage of “Bloody Sunday,” when state troopers violently attacked peaceful protesters crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. When she heard the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for clergy to march from Selma to Montgomery, she asked permission to go. Three days later, she boarded a plane to Selma with a group of other nuns from St. Louis.Sister Antona Ebo, a Franciscan Sister of Mary, was the only black sister in the delegation.

“It turned out that the habit was what got everyone’s attention very quickly, because nuns had not been seen doing anything like that before. It didn’t ring a bell with me that we were getting involved with something that was hysterical and historical,” Sister Ebo said with a laugh. At 94, she remains as involved as she can be in civil rights efforts in the city.

While their exact impact may be impossible to gauge, the sisters’ presence on the front lines in Selma shocked and upset people, even members of their own religious communities, who thought it inappropriate for nuns to be engaged in such activism.

“I received many letters, as I’m sure all six of us did, saying that nuns shouldn’t participate in these things,” Sister Anne Christopher, now Therese Stawowy, said in an interview with Webster University. “I can’t tell you all of the words of those letters, but some of them I still have today. They shook me up. We were distraught by the letters we received and the fact that a couple of times we were asked not to speak at events after we were invited.”

While the marches succeeded in garnering support for the Voting Rights Act, which was passed later that year, the struggle for racial justice in St. Louis continues over issues like police violence, mass incarceration and the geographic segregation that is a legacy of housing discrimination.

The New Selma

This September, at the first protest after Jason Stockley (who attended Althoff Catholic High School) was acquitted, local activist Tory Russell told the crowd: “St. Louis is the new Selma. Let me say that again: St. Louis is the new Selma.”

For the Catholic community in St. Louis, the parallels between their city and Selma were also evident in 2014. Two weeks after Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, was shot by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Mo., a majority-black suburb of North St. Louis, Archbishop Robert Carlson re-established the archdiocese’s Human Rights Commission, the same group that organized the sisters’ trip to Selma in 1965.

Today, the Catholic Church is again in a unique position to galvanize social justice efforts in St. Louis. It is the largest denomination in the area and runs around 30 schools; its members are mostly white. After the Stockley verdict, the largely black Missionary Baptist State Convention of Missouri reached out to the Archbishop Carlson for support.

“Their reach is so much greater,” the Rev. Linden Bowie, president of the Baptist convention, told the National Catholic Reporter.

Today, the Catholic Church is again in a unique position to galvanize social justice efforts in St. Louis.

In response to the Rev. Bowie’s request, the archdiocese organized an interfaith prayer service held downtown at Kiener Plaza, just steps from the Old Courthouse where Dred Scott sued for his freedom from slavery, which he was ultimately denied in the Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court case of 1857.

At the interfaith service, Father Ron Mercier, head of the Jesuits’ Central and Southern Province, quoted Pope Paul VI:

Those who have raised their voices in protest since last Friday’s verdict remind us that for too many people in this city we love, justice remains an unfulfilled reality. The sin of racism, and the injustice it breeds, ultimately deprives all of us of the ability to be at home, to know peace. As protesters have reminded us, those still burdened by the legacy of slavery know in a deep, visceral way what it feels like to be aliens in their own city, to see their lives given little account. Yes, we need to pray today for the gift of peace, a gift that God yearns to give us; but we must hear, too, God’s challenge to build justice.

St. Louis Catholics, led most visibly by official structures like the Peace and Justice Commission that was established after Ferguson, are working quietly to achieve justice.

After the unrest began in Ferguson, the archdiocese was active in racial reconciliation efforts, holding a series of Masses and interfaith prayer services in North County and collecting donations for social services in the area.

The Jesuits have continued their social justice efforts as well, operating an elementary school and a parish in North St. Louis. A spokesman for the university also said the school is examining its slaveholding past in preparation for its bicentennial in 2018. The law school is focused on mass incarceration, and the university established an associate’s degree program for inmates and prison workers. It is also planning a career fair for ex-offenders.

Father Chris Collins, who works on the Peace and Justice Commission, said that with some companies in St. Louis facing a labor shortage, increasing work opportunities for the formerly incarcerated could be a win-win solution.

“People from different political stripes can agree on a lot of these things,” Father Collins said. “I’m hopeful.”

He also sees potential for the archdiocese to work on racial reconciliation with the city and county police. Many of the officers, he said, are Catholics. He asked, “How might mediation within the Catholic community play a role in trying to find common ground to work on repairing the relationships between the African American community and police?”

St. Louis’ white Catholics have learned throughout history that challenging one another and seeking common ground with marginalized groups are the two most effective strategies for achieving justice.

Father Heithaus, Cardinal Ritter and the sisters challenged their communities’ racism, even when that meant facing ridicule. They bridged gaps by bringing white and black Catholics together in the university’s classrooms and marching with the black Protestant leaders of the civil rights marches in Alabama.

The city’s racial divisions persist today. If St. Louis is the new Selma, then white Catholics know exactly what they need to do: Challenge one another and work side by side with their black brothers and sisters to achieve justice and, in so doing, peace.

--

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that the St. Louis University School of Law started an associate's degree program for inmates and prison workers. This program is under the College of Arts and Sciences. The article has been amended to reflect this change.

"Today, the Catholic Church is again in a unique position to galvanize social justice efforts in St. Louis."

I arrived in St. Louis just months before the death of Michael Brown. I had already been shocked by what I saw as racism in the city and the segregation of the neighborhoods. My first week in the area someone actually said to me in reference to Jews, "you know how they are." That was mild in comparison to some of what was directed toward persons of color and especially African Americans.

I have spent the last three-years confronting racism everywhere I find it while trying to understand what fears motivate it. I can't. What I have seen is a large caucasian community that is unwilling to see the institutionalized racism in this area. It could be that they have never been in integrated cities or have never worked or socialized with people that they see as other. It does help that our churches are also largely segregated. While I understand the point of parish boundaries I think they make it worse.

As a Catholic still relatively new to St. Louis I applaud this article and hope more will follow.

Thank you for this article. It should be pointed out that Archbishop Ritter had already desegregated the schools in the Archdiocese of Indianapolis in 1944, before he was transferred to Saint Louis. He met similar opposition. http://bit.ly/1VhidmA

I do not recall, in all the years of my elementary or high school Catholic religion education, ever hearing from priests, nuns, or laypersons that racist beliefs, attitudes, and acts were serious sins. Never until my mature years did I ever hear it from a pulpit at Sunday Mass. Certainly never in a discussion about proper preparation for confession!

I really wonder if anything in my 70+ years has changed in Catholic religion education at all?

Thank you for this article. One correction I would make is that the associates degree program that Saint Louis University offers to both inmates and officers/employees at the state prison in Bonne Terre was not established by the Law School; instead, it was begun as a certificate by the Department of Theological Studies, and it is currently under the auspices of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Thank you for your comment. I've updated the article with a correction.

In the mid-1960s a documentary was made in the U.S. heartland of Nebraska at a Lutheran church. The members of the congregation there agreed to allow filming access in their attempt to integrate by association with an African-American church in the vicinity. What actually transpired is a painful account of the difficulties and conflicts that arose in the attempt that still rings true to this day. The Youtube link to the film, titled, "A Time for Burning," follows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5rokAeImLY (Other website sources are also available)

I am grateful for the continued attention paid by this weekly journal to institutionalized and other forms of racism that will not be dismissed until we come to grips with its legacies and unresolved travesties as a nation and as a church.