The current imbalance between supply and demand in the labor force should be good news for American workers still waiting to see a few extra bucks in their pockets after decades of income stagnation. Unfortunately, the nation’s 4.3 percent unemployment rate is not translating into fatter paychecks. Wages for most U.S. workers are still stagnant. In a tightening labor market, people are essentially working for less money than they did in the 1970s, at least when inflation is taken into account. What is going wrong?

According to some economists, part of the downward pressure on wages comes from the vast reserve of workers who, despite that low official rate of unemployment, remain on the sidelines of the formal economy. These discouraged workers are no longer tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics because of their long absence from the labor force, but many are still competing for full-time jobs. At the same time, mismatches between skills and job openings, as well as less direct effects on employment capacity (like the nation’s opioid epidemic), are keeping many U.S. workers from jobs with good wages.

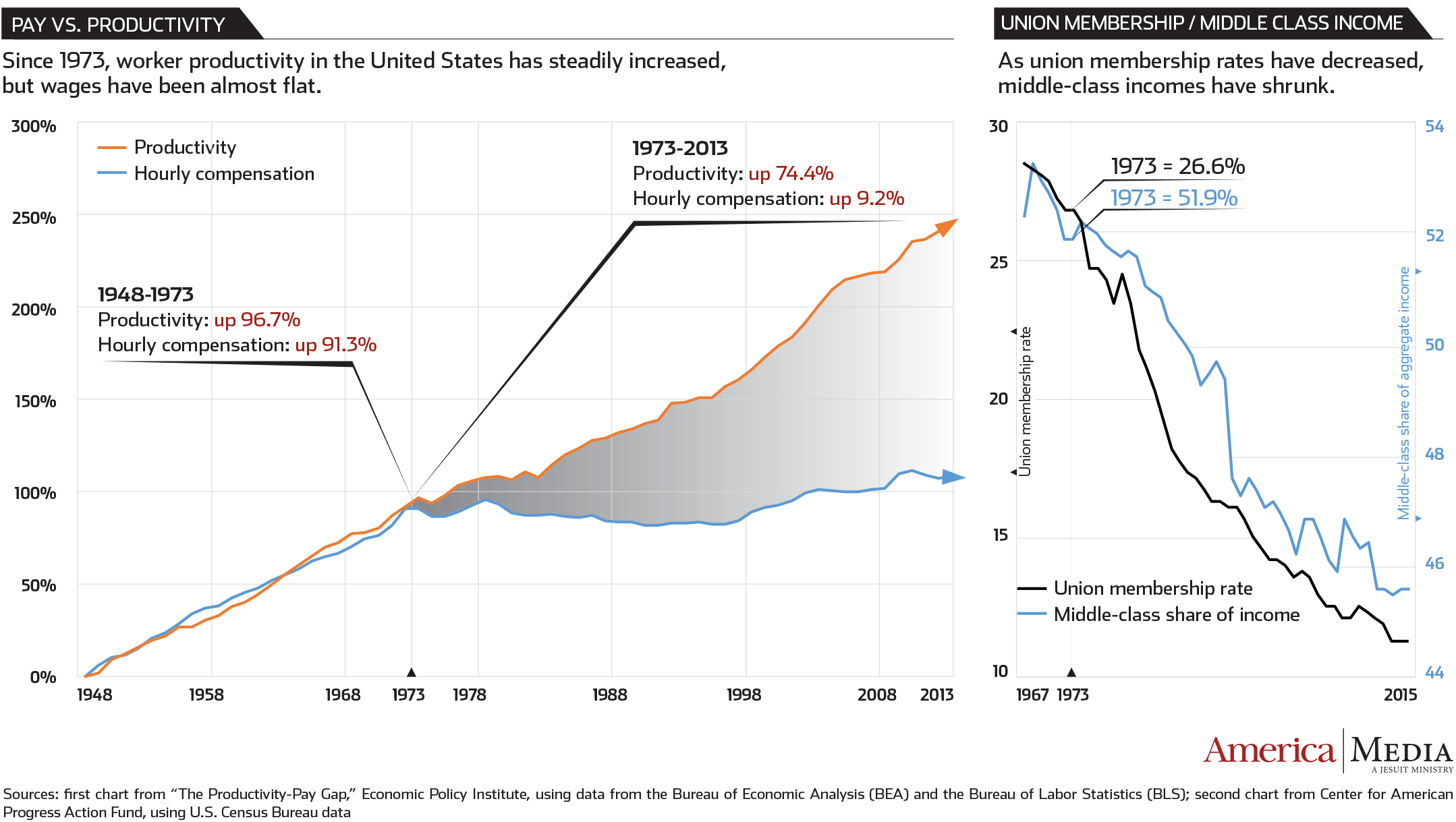

Labor’s decline just about matches up to the swan dive of middle-class income in the United States since the 1970s.

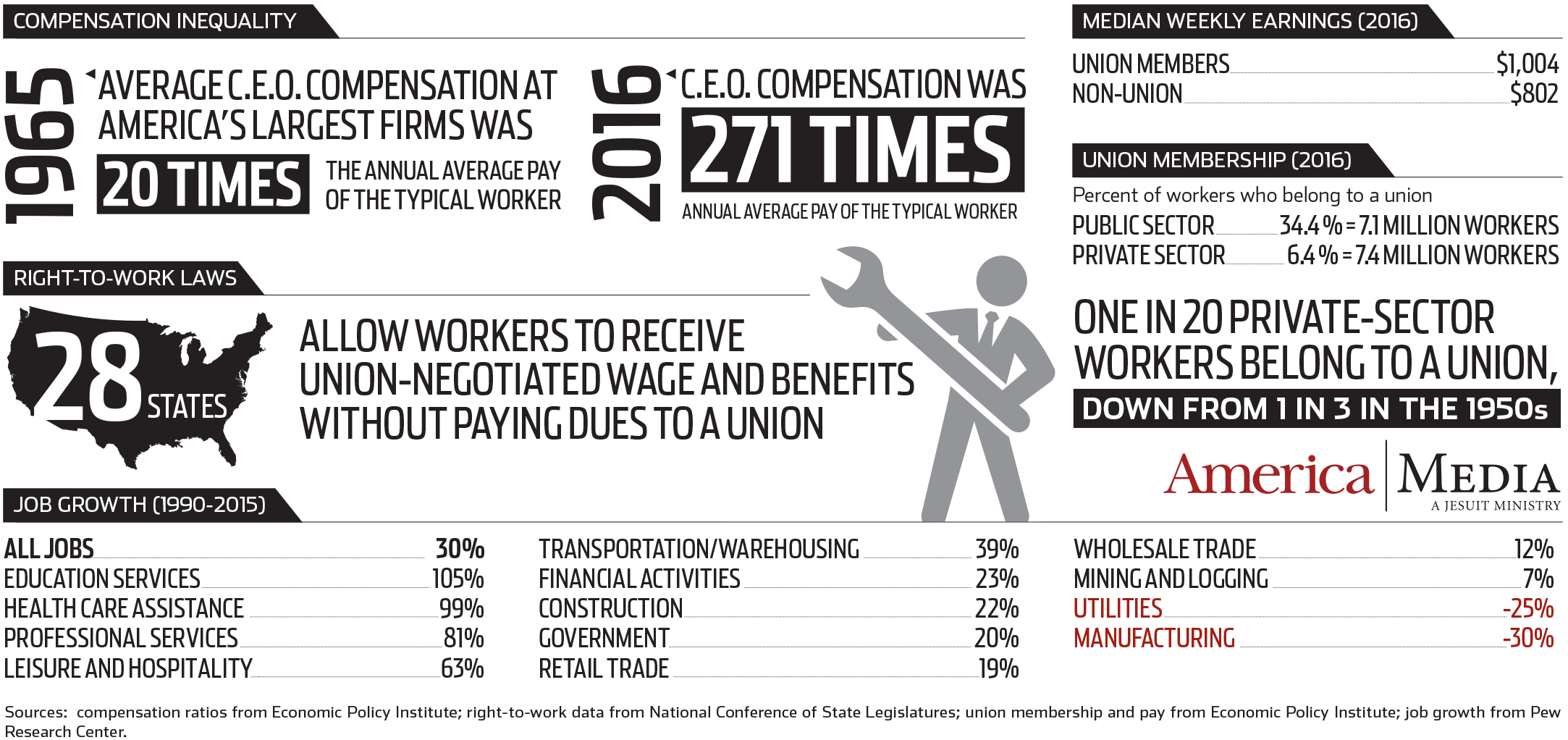

But there are deeper issues that contribute to the withering of worker income and to destructive inequities in wealth distribution. The long-term decline of organized labor surely has had an impact. (See infographics on page 14.) In the not-too-distant past, organized labor could produce sizable ripple effects beyond its membership. Even nonunion workers benefited when organized labor pushed wages higher or scored improved job benefits or working conditions. Labor’s decline, in fact, just about matches up to the swan dive of middle-class income in the United States since the 1970s.

In the public sector, with 34.4 percent of workers represented by a union, organized labor is an embattled, if stubborn presence. But in the private sector, unions have essentially been eradicated. Nationally, organized labor represents just 6.4 percent of the workforce.

Without organized labor on the watch, upper management has claimed an increasing share of national income. In 1965, corporate C.E.O.s could anticipate earning 20 times more than one of their line workers; now, after peaking at 376 to 1 in 2000, that ratio is an astonishing 271 to 1. From 1978 to 2014, top management compensation increased by just under 1,000 percent—double the stock market’s growth and about 10 times the compensation growth experienced by workers over the same period. Class warfare indeed.

Catholic social teaching has wrestled with such inequities in a number of ways, among them by calling for a just wage and a preferential option for the poor as mechanisms for mitigating imbalances, and even challenging the notion of private wealth itself with the concept of the universal destination of goods—under which, as St. John Paul II said, property “must always serve the needs of peoples.” But rarely has economic inequity been challenged as directly as it has been by Pope Francis. In “The Joy of the Gospel” he wrote: “Inequality is the root of social ills” (No. 202). In a 2013 speech at the Vatican, the pope targeted disparity as a “new, invisible...tyranny...which unilaterally and irremediably imposes its own laws and rules.”

He is right to be concerned.

Concentration of wealth is quickly followed by outsized political clout, closing a circuit that only exacerbates economic inequities. Because of this confluence of wealth and power, tax, spending and labor policies that favor the already wealthy become codified in Washington and state capitals around the nation. Among them has been so-called right-to-work legislation.

In right-to-work states, workers may still form unions, but employees are not required to pay the dues that support them. That means “free riders” can enjoy whatever wage or benefit improvements unions are able to negotiate without joining their locals. In practice, right-to-work legislation has been a union killer. And once the unions and the power of collective bargaining they represent are out, no civic entity represents workers when the rewards of a robust economy are divvied up.

That legislative model is now being applied at the federal level. The National Right-to-Work Act, introduced most recently in Congress in February, has been gaining co-sponsors.

The president’s signature on a national right-to-work law could be the coup de grace for organized labor in the United States, a loss that will accelerate the wealth inequity that is already proving economically and socially ruinous.

A sobering account of what happens when unions decline. For even more detail, see Jake Rosenfeld's WHAT UNIONS NO LONGER DO (Harvard U. Press, 2014). His exhaustive analysis demonstrates that, among other things, minority workers suffer the most when the labor movement is diminished.

While reading Kevin Clarke's comment about John Paul II "challenging the notion of private wealth itself," I am reminded that, read fully in Centesimus Annus (building on Leo XIII), JP II's views of ownership private property--that such is needed to preserve and develop such property and keep it from waste and destruction--is consistent with Catholic teaching since at least Aquinas. That the ultimate destination of goods is to the common good, is part of that teaching (again, since Aquinas) but not the entire teaching, and no challenge to it.

The decline of unions is not entirely attributable to 'right to work' laws or corporate opposition. And as with most trends, it has been accompanied by benefits for many consumers. My father was a union bricklayer, the product of a lengthy apprenticeship that taught him all the artistry of that trade, how to read blueprints, execute intricate designs, etc. Brick was replaced by other exterior building materials such as aluminum and vinyl siding for homes and apartments, steel, glass and aluminum cladding for commercial buildings. Those require far less training for the installer, and far fewer work hours to clad a building. Brick fell out of favor. Those trends, while painful for many bricklayers, made housing more affordable for many families. Similar trends affect other trades and technologies. These trends leave unions with less power, and in many instances workers see little benefit in joining a union (and paying dues) to a union that has very little ability to negotiate on their behalf. The value proposition that made unions powerful--their ability to provide a well-trained tradesman through apprentice programs-- fell apart as demand for such well-trained workers fell off in many areas.

Wages for non supervisory workers peaked in 1973. You can actually see the month when this happened. It had nothing to do with unions.

What changed? In 1965 the immigration laws were changed and millions of low skilled workers were admitted to the US. The laws of supply and demand took over and within a few years wages at the low end of the scale were affected because of the increased supply of these low skilled workers.

It is impossible to repeal the laws of gravity. It is impossible to repeal the laws of supply and demand too since it is built into human nature. But we keep on trying with legislation and regulations and the results are always unexpected and rarely positive. When this happens, a few benefit while the poor are hit the hardest.

Also CEO pay rises are a bad comparison. Business has gone global in the last 40 years and the decisions of higher management affect sales world wide. The economic effect of an industrial worker has not changed in the same way during that time. A better example of this effect is sports salaries and those of entertainers. The have probably increased more than CEOs during this time due to world wide exposure.

Income inequality does not create poor. It is a convenient scapegoat to blame income inequality but other structural regulations is what usually creates poverty. Excess wealth goes somewhere and usually has the effect of helping others.

The image of the rich doing nothing with their money except count it is a cartoon from Disney comics of Scrooge McDuck. They invest it and the rest of us get back part of this for ourselves in better jobs or better cheaper products.

Sorry but Rosenfeld and economic historians disagree. If we are analyzing the 1970s, the factors were stagflation, and the energy crisis. The attacks on labor began as well with a jump in aggressive anti-union tactics (=failed strikes & organizing campaigns); by the late 1970s the concessions and give-backs began. Douglas Fraser made quite a stir when he resigned from the the Labor-Management Group in 1978. Fraser described the viciousness corporate America (http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/fraserresign.html).

Immigration played little role, if any: the number of immigrants admitted on the eve of the 1965 law was 296,697; in 1975 it had increased to only 385, 378.

In “Winner-Take-All Politics”, authors Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson’s analysis of 1978 also aligns with Fraser’s.

If you look deeper you will see a very changing pattern. Most of the immigration prior to 1965 came from Europe and Canada. After the new immigration law in 1965 this changed dramatically. Not only the region of origin change dramatically but there was a big increase in the number of immigrants.

People born outside US living in US by census year

1950 10.3 million

1960 9.7 million

1970 9.6 million

1980 14.1 million

1990 19.8 million

2000 33.1 million

2014 42.2 million

Immigrants from geographic regions percent of total

European/Candian Origin

1960 84 percent

1970 67.8 percent

1980 42.4 percent

1990 25.8 percent

2000 18.8 percent

2014 13.6 percent

Mexican Origin

1960 6 percent

1970 8.1 percent

1980 15.6 percent

1990 21.7 percent

2000 29.4 percent

2014 27.7 percent

Other Latin American Origin

1960 3.5 percent

1970 10.8 percent

1980 15.5 percent

1990 20.8 percent

2000 22.2 percent

2014 23.9 percent

Immigration of low skilled workers was the main driver of stagnant wages at the low end. At the same time the computer then internet revolution was driving wages up and up at the high end.

The European immigrants of the storied "Ellis Island" narrative were mostly from rural or urban poor, so I don't see the point. The key issue is: did the upswing in immigration to the USA in recent decades (really after 1980) cause growing inequality? Economic historians respond "no." At least not directly: some employers in the service sector paid low wages (and harassed these newly-arrived), but the prime determinant about wages was, and is, the presence of unions. BTW, immigrants and their children make up a large percentage of new union members.

Again you will have to look a little deeper. By the time the change in immigration laws took place, the number of jobs in the country that former immigrants took was shrinking fast not growing. Farming which employed over half the population in the early 1900's is now down to about 2.5 % of the population and was disappearing fast after World War II. Manufacturing and Mining jobs were declining also. Manufacturing jobs were getting automated and the economy was changing dramatically. The states east of the Mississippi are scattered with small towns that once thrived on farming, mining and manufacturing. Now they make curious relics of a time gone by.

From the 1924s to the 1960's there was relatively little immigration and the economy was humming in the 1960's. The previous spike in immigration was in the early 1900's from Italy and Jews from Eastern Europe.

But some thought a part of the population was being left behind and that is the origin of the War on Poverty. So after 1965 along comes all these low skilled workers with few jobs for them. And who do they compete with, the people who were supposed to be helped by the War on Poverty. The result was that the jobs they could do were inundated with people and thus this type of immigration drove down wages for the most vulnerable in the US.

Who was hurt? Americans with less than a high school education as their wages and jobs started to disappear. Who was helped? Americans with education who could get jobs in the various service and white collar and technical areas. They had better jobs and cheaper products and services. Yes, the demand for products and services by immigrants expanded the economy but not as much as their numbers.

It is simple economics. It has nothing to do with unions.

Given that, we will always need immigration but it has to be controlled and it cannot be open as some want. Some think the ability of the United States to absorb immigrants is infinite but it is not as our experience after the change in immigration laws led to the obvious economic prediction of lower wages for the low end of the economic scale.

It is easy to see the point. It is economics 101 or actually more basic than that.

Sure, we moved from an agricultural to an industrial to a post-industrial service economy. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century skilled workers were convinced that factory workers (many European immigrants) were unorganizable. By the 1930s armies of these workers joined, with enthusiasm, CIO unions. These days the same notion is applied about temp, care, and service workers. But they DO want to join unions. Weak labor laws and aggressive anti-union employers throw up plenty of roadblocks.

UAW lost 60:40 in Alabama 10 days ago. Quod erat demonstrandum.

Four percent of GDP goes toward stock buybacks, none of which helps forty percent of U.S. workers making less than $20,000. The top 400 U.S. incomes, in 2014, averaged $300 million, the majority from capital gains.

General MacArthur spoke of a policy perhaps appropriate today. “In 1948, General MacArthur declared ‘Allied policy has required…breaking up…(Japanese) commerce and industry controlled by a minority…and exploited to their exclusive benefit.’” The MacArthur quote comes from author Walter Scheidel in “The Great Leveler”.

Nobody here addresses the moral issue vis-à-vis private property. Is there a point when or at what point does the acquisition and accumulation of private property become immoral?

Mr. Kotlarz states, and I presume accurately: “The top 400 U.S. incomes, in 2014, averaged $300 million, the majority from capital gains.”

$300 million buys you a nice house, lots of nice furniture, plenty of property, and the workforce to maintain it all. But after you have bought up all those things, how else do you spend your $300 million each year in the future? And that money, he says, was mostly from capital gains from invested money, surely much larger sums, not even from doing work!

The U.S. Census Bureau reported in September 2014 that: U.S. real (inflation adjusted) median household income was $51,939 in 2013 versus $51,758 in 2012, statistically unchanged. In 2013, real median household income was 8.0 percent lower than in 2007, the year before the latest recession.

To quote just one abysmal statistic recently reported from New York City, one in seven children in the public school system is “homeless,” living either in shelters or doubled up with other families.

Unions helped to redistribute some of the wealth generated through their members’ work to their members, as well as creating a standard for income for the unorganized working citizenry as well. That unions have declined and that there is a legislative push to further that decline raises serious moral issues to my mind.

The concentration of all that extra wealth in the hands of just a few people also raises some moral issues in my mind as well.

We don’t seem to get explicit moral direction from the Church on these issues, at least as I see it. Lots of discussion and disputation, like here, but little direction!

Finally, the various dioceses and agencies of the Church in the USA haven't been all that receptive to union organizing in their own workplaces.

Labor Day in the past was the occasion for prominent individuals to speak about the importance and necessity of unions. The article follows this tradition. We all need to write the members of Congress about the National Right-to-Work Act

In addition to wages, unions also protected employees. A recent article in the NY Times looked at injuries on union building sites versus non-union. The non-union sites had significantly more accidents reported. Part of that might be the training that unions required, part of that might be a greater awareness & reporting mechanism for unsafe practices.

Higher wages without greater benefit to employers just won't sell. My father's Union was successful not just because of organizing in the 40s and 50s, but because of reliable, trained, and efficient Ironworkers who took pride in their work. But manufacturing has gone overseas due to Global competition, and many construction jobs are now filled by a surfeit of cheaper immigrant labor.

Unionizing works best where there is a skilled labor pool in high demand. It works least well for low skilled overpopulated labor pools. Think of a world population of workers competing for jobs that can be located anywhere in the world, and the higher paid American worker is at a distinct bargaining disadvantage.

The solution if for the U.S. worker to upgrade his or her education and skills for a tech and information economy, rather than to yearn for the good ole days when dad or granddad could make a decent income on the assembly line.

The focus should not be on artificially raising wages and therefore prices, but government and private investing in affordable occupational training for the displaced U.S. Worker. There simply aren't enough high tech and scientific workers to fill the demand. The problem is so severe at so many levels that some companies are providing basic education for their own work forces because the U.S. formal education system has failed them.

The claim that the US doesn't have STEM workers is a myth: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/04/the-myth-of-americas-tech-talent-shortage/275319/

As for "artificially raising wages," the whole "free market" is artificial. Some quick examples: the AMA regulates the number of medical degrees granting institutions; businesses wring subsidies out of cities to build their stadiums, hotels, etc.

Interesting. But several of my friends who own businesses report serious, long-term problems finding employees competent in high-school-level (or what used to be high school level) math. One found the problem serious enough to discuss it with the local school board. These are not technology jobs, but basic manufacturing and related positions. So not the jobs that attract H1-B workers, but full-time jobs that pay good wages, benefits, etc. By the way, the last section of the Atlantic article offers evidence that the article's headline and opening thesis may be flawed. There are also a number of international studies that show the relative lack of math and science literacy of American adults compared to those of other developed countries. Cheers.

I think your friends have a point, i.e., there are regional deficiencies in skills. The national studies that I read conclude that the "skills gap" is (nearly) non-existent. I haven't seem any evidence about manufacturing gaps but there are in several skilled trades, e.g., welding, HVAC technicians, etc.