How much can we tell about a pope by the name he chooses? Sometimes a lot—as seems to have been the case with Pope Francis, whose simplicity and efforts at reform of the church did often echo the life of St. Francis of Assisi. Sometimes we can tell very little: The fifth-century pontiff Pope Hilarius, for example, seems by all accounts to have been pretty humorless (kidding, kidding). But with each new pope, the question does arise: Why that name?

As James Martin, S.J., noted in America on May 5, the choice of his name “is said to be the new pope’s first important decision.” The interplay between history and the choice of a papal name is a complex and delicate one. Should a new pope honor the memory of his predecessor? Indicate a program for his pontificate? Choose the name of a saint to whom he (or the people of his homeland) is devoted? Or—as has been the case often enough before the last few centuries—should he just keep his baptismal name?

Pope Leo XIV, formerly Bob from Chicago, picked one of the most common names in history for a pope: Only John, Gregory and Benedict have been used more. (Leo is tied with Clement, and just ahead of Innocent.) But it is a name with great resonance in modern church history, and one whose selection suggests quite a bit about what the reign of the new pontiff might be like.

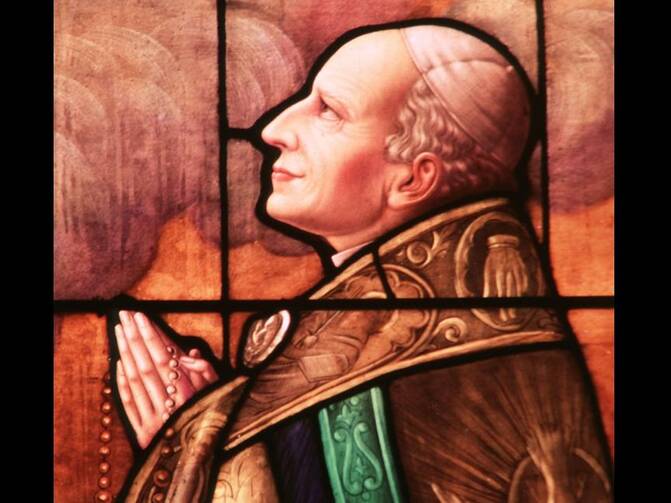

Matteo Bruni, the director of the Vatican press office, seemed to confirm yesterday that the choice by then-Cardinal Robert Prevost, O.S.A., of “Leo XIV” was meant as an echo of one of the 19th century’s great defenders of worker’s rights, Pope Leo XIII. Pontiff from 1878 to 1903, Leo XIII authored the encyclical “Rerum Novarum,” the ur-text of Catholic social teaching. The new pope’s name, accordingly, is a “direct recall of the social doctrine of the church and of the pope that initiated the modern social doctrine of the church,” Mr. Bruni told reporters, adding that the name is also a reference to “men and women and their work, also in the time of artificial intelligence.”

So what was “Rerum Novarum”?

‘Rerum Novarum’

The great “social encyclicals” of the church began with “Rerum Novarum” in 1891. Other examples (depending on whom you ask, this list might be longer or shorter; de gustibus non disputandum) include “Quadragesimo Anno” (1931), “Mater et Magistra” (1961), “Pacem in Terris” (1963), “Populorum Progressio” (1967), “Laborem Exercens” (1981), “Centesimus Annus” (1991), “Caritas in Veritate” (2009), “Laudato Si’” (2015) and “Fratelli Tutti” (2020), but they are all in a way descendants of that original 1891 text. Two of them—“Quadragesimo Anno” (“Forty Years”) and “Centesimus Annus” (“Hundred Years”)—make that explicit in their title.

A sharp critique of the treatment of the working classes after the Industrial Revolution, “Rerum Novarum” made it clear that while the church was no friend of socialism (which was becoming the specter haunting Europe; The Communist Manifesto had been published four decades earlier), it was all the more opposed to unfettered capitalism and the abuses concomitant with its flourishing. The encyclical also marked a new era in papal teaching: the intervention into social questions that had previously not always been presumed to be under the umbrella of teaching on faith and morals.

Why the new approach? “At this moment the condition of the working classes is the question of the hour,” wrote Pope Leo XIII in “Rerum Novarum,” sounding a bit like Karl Marx himself.

While Leo’s encyclical recognized the right to private property—sorry, Marx—it also insisted upon the rights of workers, including the right to a just wage and to safe working conditions. Note that “Rerum Novarum” and the church’s later social encyclicals didn’t mean a “minimum wage” when they speak of a just wage, but a “living wage,” defined as the remuneration that would allow a worker to provide for himself and his family.

Putting patriarchal notions of family and society aside, this principle sets church teaching starkly at odds with the capitalism practiced in the 19th and 20th centuries as well as the globalized economy we live in today. It is not easy—though many try—to square a modern American notion of a just society with the church’s teaching in “Rerum Novarum” and its corollary encyclicals.

The theologian Kenneth R. Himes, O.F.M., noted in America in 2021 that while “Rerum Novarum” was obviously aimed at economic structures where physical labor was the dominant source of economic output (and locus of exploitation), it doesn’t mean that the encyclical is irrelevant in modern economies like those of the United States. In fact, it has particular relevance with regard to the “gig economy” that has emerged in recent decades.

Father Himes defined such an economy as “a labor market where there is a prevalence of short-term or freelance jobs instead of workers in full-time employment in a more settled position that offers opportunities for career advancement, compensation that includes benefits, procedures for determining and appealing workplace rules and a measure of job security.” A few years later, we might add to his concerns the issue Mr. Bruni brought up yesterday: the rise of artificial intelligence as a new source of downward pressure on wages and worker’s rights.

In the absence of safeguards like labor laws, the right to organize into guilds or unions and a societal recognition of the dignity of work, Father Himes noted, our modern economies echo Pope Leo XIII’s concerns about the world of the Industrial Revolution. “He noted that if, from necessity, workers accept harsh conditions due to an employer’s unwillingness to offer better conditions, then the worker is not freely consenting but is the victim of unjust coercion,” Father Himes wrote. “Increased pressures for labor market flexibility may effectively mean transferring financial risks and economic insecurity onto workers and their communities.”

In other words, if Pope Leo XIV is really signaling with his choice of name that he is going to be the pope to advance the teachings of “Rerum Novarum” and later social encyclicals, he is taking a public, prophetic stance against many of the undergirding principles and assumptions of the global economy. If Laura Loomer thinks he’s a “woke Marxist pope” already, she ain’t seen nothing yet.

Americanism

“Rerum Novarum” was just one of a great many documents to issue from the pen of Pope Leo XIII during his long reign. An apostolic letter from 1899 might offer an ironic commentary on our new pontiff’s choice of name: “Testem Benevolentiae.” Written four years before Leo’s death, the encyclical condemned “Americanism” as a heresy. While assuring its recipient (Cardinal James Gibbons, the archbishop of Baltimore, but clearly meant for a larger audience, including Isaac Hecker) that he was not criticizing “the characteristic qualities which reflect honor on the people of America,” Pope Leo still looked at the American democratic experiment with a distinct squint in his eye.

Though “Americanism” was never explicitly defined, it included a loose collection of intellectual principles that Leo and others saw blossoming in the United States but as anathema to the church, including the separation of church and state, freedom of speech, ecumenism and the belief that democracy was the political philosophy proper to all cultures. Many of those principles have since been accepted by the church itself, particularly in the documents of the Second Vatican Council; but at the time, their adherents found few friends in Rome.

Of course, what is meant by “Americanism” today is a rather different thing, often meaning more a nationalistic “America First” ideology. That’s not what Leo XIII was criticizing at all. But it does make the choice of Leo XIV—by an American-born pope—an occasion of some irony.

Other Leos

What of the other 12 Pope Leos? Might our current pontiff be honoring or referencing one or more of them in his choice of name? The first Leo, known as “Leo the Great,” was a fifth-century saint and a doctor of the church; in 2008, Pope Benedict XVI called Leo the Great’s long reign (440-461) “undoubtedly one of the most important in the Church’s history.” His greatest achievement if you’re a theologian (actually, even if you aren’t) was his contribution to the Council of Chalcedon (451), an ecumenical council of enormous importance in the history of the church that clarified central questions about the identity of Jesus Christ—specifically defining him as one person having a divine and a human nature.

A year later, however, Leo the Great faced another challenge that history probably remembers him for more than his participation in a debate about the hypostatic union: Attila the Hun invaded Italy and sought to sack Rome. According to legend, Pope Leo met with Attila at Mantua and convinced him to turn back. (You can see Raphael’s famous fresco depicting their meetup here.)

What if Leo the Great was the inspiration for the new pontiff’s choice of name? If so, maybe he’s signaling something else: that he is the pope we need to negotiate with the world’s barbarians.