Bobby Kennedy, a politician unafraid of love

Robert Kennedy, if he had lived, would now be 91. When he was assassinated in 1968, he was a young man who had been with us for a long time, or so it seemed. He was chasing Communists with a family friend, Joe McCarthy, and then, with other senators, chasing mobsters and, at enormous cost, the Teamster boss, Jimmy Hoffa. Along the way his brother Jack won the hearts of my Notre Dame class of 1960. Bobby was there, beside our first Catholic president, at each dramatic event of Jack’s not-quite-three-year presidency. Then he stood, broken it seemed, with his parents and Jackie, as the Kennedy we all loved best, murdered, was laid to rest.

There were hard days for Americans and for Robert Kennedy in the years that followed: cruel violence aimed at justice-seeking African-Americans and at Mexican-American farm workers, summer riots in major cities, an unjust and seemingly never-ending Vietnam war. Robert Kennedy moved through those days with us, sharing our anger and anxiety. He showed us a way, if not the way, his heart touched by suffering and injustice and his love poured out to children, to peacemakers and justice-seekers like Cesar Chavez and Albert Luthuli. He seemed at times liberal, at others conservative, but mostly he seemed to share our uncertainty about what should be done.

The next steps, for him and for us, grew a bit clearer when in spring 1968 he finally campaigned for president—for a short 85 days. In April we wanted to be with him as he told an inner-city community in Indianapolis that Martin Luther King Jr. was dead, then shared his own pain at the loss to violence of “a member of my family.” He was, we wanted him to be, our voice, our presence, a sacrament making real something of the love we had, or wanted to have, for our American family. Then, suddenly, he was gone, and a piece of ourselves went with him. “When Robert Kennedy was assassinated,” Congressman John Lewis said, “something died within America. Something died within all of us who knew him.”

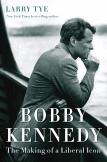

So it may be a bit risky for Americans of a certain age to read this excellent new biography, Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon. The book is enriched by firsthand interviews with Bobby’s wife, Ethel, some of his children and his big circle of staffers, friends and “seduced” reporters who “fell in love” with him. Reading about Bobby is hard for older Americans, especially Irish Catholic Democrats, for whom Kennedy family stories are memories more than history. Younger readers, who have lived in our post-1960s world, may find it hard to understand the Kennedys—or to share the emotions of readers who recall the days when the country, our country, really mattered, its graces personal gifts to our families, its sins our sins, its future our responsibility.

Norman Mailer, who knew Bobby, said a few years after Bobby’s murder that “in America the country is the religion.” Perhaps only people who have experienced religious conversion can understand what it meant when Jack Kennedy, “the Brother,” told us to “ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.”

Some among the courageous young African-Americans who stood up to injustice, like John Lewis, invited the rest of us to consider that they acted, and sometimes suffered and died, for us. With Martin Luther King’s help they made present American promises of liberty and justice for all, to say nothing of the virtues of the Christian Beatitudes. In 1963 Dr. King pointed to the object of civil faith, the beloved community still to come; then, five years later, tired and discouraged, he bore witness to undying hope for that dream the night before he was murdered in Memphis. Some Americans, black and white, thought Bobby carried on that flame: “I felt this was a guy that I could give my life for, like I would have for Martin,” King’s acolyte Andrew Young said. For a few months he did, until he too was taken.

And we, the rest of us, with saints and prophets gone, were left behind. Our civic religion went back to its church, fully armed; and the beloved community, with its promise and responsibilities, faded from our common life.

So Larry Tye’s Bobby Kennedy might find a place in American saint studies, not as hagiography, though there is some of that, but as one of those critical but loving accounts given by truth-tellers when asked about sainthood for people like Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton. Robert Kennedy’s biographer recalls the cartoonist Jules Feiffer’s report on a “bad Bobby” (Joe McCarthy protégé; anti-Jimmy Hoffa zealot; John Kennedy campaign capo; go-slow adviser to civil rights heroes) and a “good Bobby” (loving son, brother, husband, father; advocate, eventually, for children and poor people; dreamer of democratic dreams). Bad Bobby measured all by, and would risk everything for, the good of the Kennedys. Good Bobby would do the same, with the same tough-minded realism, for the whole human family, especially its most vulnerable members. He seemed to be transcending his internal contradictions when, too early, he was gone.

Catholics with their “sacramental imagination” might make sense of what this man meant to some of his contemporaries.

Other politicians might represent us, other public figures might speak for us, but at times John F. Kennedy and, for a moment, Bobby, were us. Irish chieftains, divine right kings, ordained priests were once like that, leaders who embodied, were at one with, the people they served. We make light of such old-fashioned images of solidarity until, all at once, we experience something like that: Dr. King on the Mall, Bobby Kennedy in that Indianapolis neighborhood, Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” at a funeral in Charleston, S.C., any of us at a funeral for a fallen soldier or first responder. Bobby Kennedy’s “we” expanded, step by painful step, from the Kennedy family to the American people, our people, then, first steps, to the world. Martin Luther King’s “we” did the same, with more pain and deeper reflection. Who, we all ask, are “my people”?

Readers of Bobby Kennedy will learn a lot about Bobby, his family and the politics of America during a span of just over 20 years. They will be reminded that while politics and policies are shaped in part by economic and social forces, individuals do make a difference. In the famous “Ripple of Hope” speech to young people in South Africa (excerpted below), Bobby said that even the smallest effort to help others or combat oppression could help change the world. Closer to home he knew that some people, for a full spectrum of motives, seek power, and political power always has some measure, large or small, of discretion. On the brink of nuclear war J.F.K. could have ordered an attack on Cuba; later Bobby might have apologized to Lyndon Johnson; or he could have chosen to run for president before Eugene McCarthy. His choices made a difference.

So the Bobby story may reopen imaginations about the trajectory of our American history, and our place in it. For those for whom it is not a memory, Bobby’s life may provide a clue or two to responsible re-engagement with American civic life. Larry Tye thinks Bobby became a “liberal icon” though he worked with conservatives and had little use for most liberals he knew. He bridged emerging gaps between suburban liberals and urban bosses, between black and Latino and white workers, even between ideological divisions of right and left. Most of all, what set him apart was not his familiarity with the knotty fabrics of American politics but his unique capacity to learn from experience and move beyond ordinary political categories to speak at times, without embarrassment, of love. Once that love opened minds and hearts to the common good based on an almost religious devotion to the American people. That prophetic Americanism, once the seedbed of historic reforms and brought to new life by Dr. King and the maturing Bobby Kennedy, remains the missing ingredient in American politics and culture.

Few will have the greatness to bend history itself, but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, and in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation…. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lives of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope and, crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, these ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance…. Only those who dare to fail greatly can ever achieve greatly. It is this new idealism, which is also I believe the common heritage of a generation which has learned that while efficiency can lead to the camps at Auschwitz, or the streets of Budapest, only the ideals of humanity and love can climb the hills of the Acropolis.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Keeping the Flame Lit,” in the October 10, 2016, issue.