The Hurt Life

I’ve heard it said: hurt people hurt. If anyone was ever hurt as a child, not physically but emotionally, it was Tennessee Williams. His mother Edwina’s denial did the hurting, denial she turned into an art form, which her son turned into art. And John Lahr, senior drama critic of The New Yorker for over 20 years, has written a beautiful biography of the artist.

What Edwina denied, probably because her father, an Episcopalian clergyman, denied it in himself, was the flesh. Williams believed that his maternal grandfather, the Reverend Dakin, had been blackmailed because of a homosexual encounter in Key West, Fla. Williams lived for much of his childhood with both his parents and the Reverend Dakin and his wife. As Lahr writes, “Williams, who often complained of feeling ‘like a ghost,’ grew up in not one but two haunted households where secrets and the unsayable suffused daily life with a sense of masquerade....”

He grew up, then, in a theater of sorts, each member of the family a player—except perhaps his father, Cornelius, also known as C.C., who believed only in making money. In this toxic environment, Williams turned to writing, something Edwina encouraged to drive C.C., who considered all writers loafers, up the wall. But Williams succeeded better than she probably wanted him to and escaped C.C.’s philistinism and what Williams called his mother’s “monolithic Puritanism.” His play “The Glass Menagerie,” based upon his family drama, was a huge hit on Broadway from its opening night, March 31, 1945.

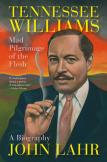

From then on Williams hurled himself into his writing and into what he called a “mad pilgrimage of the flesh,” which, aside from the writing, meant for Williams a promiscuous homosexual “cruising” lifestyle relieved by the occasional stable relationship with a man he loved. His longest relationship was with Frank Merlo, with whom Williams shared a house in Key West, a place Williams loved for “the water, the eternal turquoise and foam of the sea and the sky.”

But no matter how stable life was in Key West, Williams hurt the people in his relationships, both professional and personal. His erratic and sometimes perfidious behavior ultimately ruptured his collaborations with Elia Kazan, the famous director, who demanded Williams revise his plays into better shape, and his longsuffering agent Audrey Wood.

The fall of the playwright came from a combination of changing times—the romantic freedom of the flesh he had dramatized boomeranged to say he was out of date, the struggle was over—and his abuse of himself through pills and alcohol. Empty, he tried to fill himself. He tried psychoanalysis, which helped a little but which he stopped too soon; he even tried God when his brother Dakin prodded him to convert to Catholicism. He had a deep devotion to Our Lady, and, when he was receiving an honorary doctorate at Harvard, knelt before Mother Teresa, put his head in her lap and was blessed. But the pilgrimage ended with him holed up in a hotel room with booze and Seconal and an overdose, no one knows whether intentional or not.

Lahr has written a masterful portrait. How he apparently hops around chronologically while still telling the story in a progressive way, all the while supplying interpretations of the plays, something he says has been lacking in all previous biographies, defies analysis. It probably has something to do with the 12 years it took him to write it. There were only a few times when I felt a touch of vertigo and wondered where I was in the playwright’s life. And the book is gloriously free of the grinding of any personal, political or religious axes.

I can do no better than to quote Lahr’s last paragraph, which points to the heroism of Williams’s life:

In his single-minded pursuit of greatness, Williams exhausted himself and lost his way. “I want to get my goodness back,” he frequently said. If he didn’t find the light, his outcrying heart certainly cast it. “What implements have we but words, images, colors, scratches upon the caves of our solitude?” he said. In the game of hide-and-seek that he and his theater played with the world, Williams left a trail of beauty so that we could try to find him.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “The Hurt Life,” in the October 13, 2014, issue.