Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the Aug. 2, 1969, issue of America, titled ‘One Giant Leap for Mankind.’

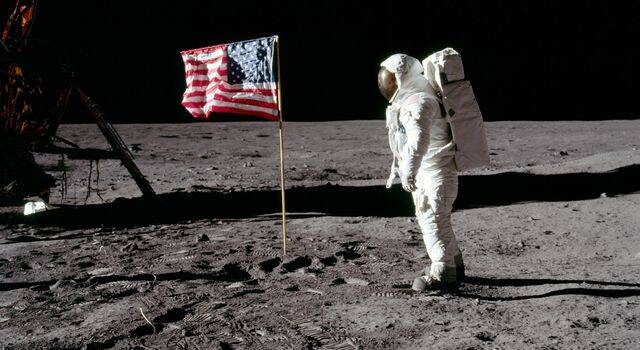

Brilliant astronomers like Galileo and Copernicus made it possible for man to take a whole new look at creation. If men once believed that the planet Earth occupied the center of the cosmos, Copernicus rudely dislodged them from this comfortable, egoistic stance. Our globe has since emerged as an infinitesimal grain of sand in an immeasurable void. Our solar system, measuring 7.3 billion miles in diameter, still is insignificantly small when compared to the universe itself. Comparable solar systems in the vast regions of space, in fact, number into the millions. On July 20, astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin and Michael Collins introduced us all in a new and dramatic way to this reality.

The sheer magnitude of the universe, as shown by technological advances, can inspire deeply religious thoughts and sentiments. Col. Edwin Aldrin’s father responded in such a religious way when he suggested to his son that he recite the Eighth Psalm from the moon’s surface. John Glenn’s response to space travel was religious, too, when he said that he felt that wherever such exploration would bring man, God would certainly be there.

The entire Apollo enterprise is so much a symbol and product of human unity as to argue its distinctively religious character in itself.

Not everyone reads these events in religious terms, however. Technology has for many had the effect of weakening the sense of the sacred, putting man without God at the center of meaning and experience, creating a neo-humanism rooted in our vast technological achievement that may well foster a wider indifference and disbelief than any earlier atheism or agnosticism. “The great problem of our times,” says Episcopal priest and nuclear physicist Dr. William G. Pollard, “is that the sheer vitality and dynamism of science tends to overwhelm everything else, to drive out all earlier visions of the real.”

Although religious responses to modern technology differ markedly, technology in itself exhibits a distinctively religious character. Genesis tells us that God instructed Adam to “till the garden and keep it.” So it happens that every breakthrough in medicine, science, peacemaking, government, knowledge or lunar technology is a fulfillment on man’s part of the Father’s mandate to Adam.

There is a profound religious meaning, too, in the collaboration of hundreds of thousands of workers—technicians, scientists, engineers, craftsmen—in myriad manufacturing plants and companies responsible for building components of the indescribably complex moon probe mechanisms. All these workers, united in a good cause, image forth the Christian ideal of polis, the human community. In addition, the moon venture envisions not just the speculative enrichment of scientists, but the benefit of the entire human community through multiple practical returns. As one example, the lunar exploration will almost certainly assist in pure weather forecasting, saving millions of dollars in harbor and maritime damage, and many lives. The main point, however, is that the entire Apollo enterprise is so much a symbol and product of human unity as to argue its distinctively religious character in itself.

Perhaps the points raised here may seem doctrinaire. Perhaps such issues are only seen today by those who stand in some felt relationship with religious belief, or with the Christian Churches, as Helmut Thielicke points out. A thoroughgoing secularist, for example, might say that the moon walk is not in the least problematic to him, that science renders all clear and intelligible, and that if some problem of a suprasensory nature were to exist, he would not look for an answer from religion.

Perhaps. But there remain others who more acutely sense the need to explore these technological wizardries for their religious values and justification. There are few more urgent tasks confronting the theological fraternity than to develop a structured response to the technological culture of our time. If the moon walk prompts our theological systems to read “go” on the latter project, the practical religious returns can be outstanding for space age man.