Editor’s note: This homily was delivered by Matt Malone, S.J., at a special live-stream Mass to celebrate the Feast of St. Edmund Campion, S.J., patron saint of America Media. You can watch the entire Mass here.

It was December 1992, on one of those long, gray winter afternoons when the world seems unbearable. For reasons I don’t recall but I surely thought were dire, I’d had enough of life, at least for the day. So I skipped the class on the history of Canada, footslogged across my dank, windswept campus and climbed the stairs to my dorm room, 8 feet by 12 feet of white painted brick and beige laminate tucked into the northeast corner of the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. Much like the solipsistic protagonist in “I Am a Rock,” that homage to loneliness by Simon and Garfunkel, I fancied myself an escape artist of sorts: “I am shielded in my armor/ Hiding in my room, safe within my womb.... I am a rock/ I am an island.”

I had left my book bag at the student union, and the only book in my room was And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic, by Randy Shilts of The San Francisco Examiner. A cutting, heart-rending account of the first five years of the AIDS epidemic, the book is hardly escapist fare. Still, I wasn’t about to traipse back across the tundra. Six hundred pages later, I closed the book and cried.

I cried that day for the people I knew who were living with AIDS and for the thousands who had already perished. I wept as well for my country: Our national conscience had failed us catastrophically. Too many decent people had allowed too many decent people to die simply because they thought that AIDS was something that didn’t happen to decent people. America’s sluggish, half-hearted response to the plight of people living with AIDS was a mortal social sin, one for which our country has yet to fully atone.

America’s sluggish, half-hearted response to the plight of people living with AIDS was a mortal social sin, one for which our country has yet to fully atone.

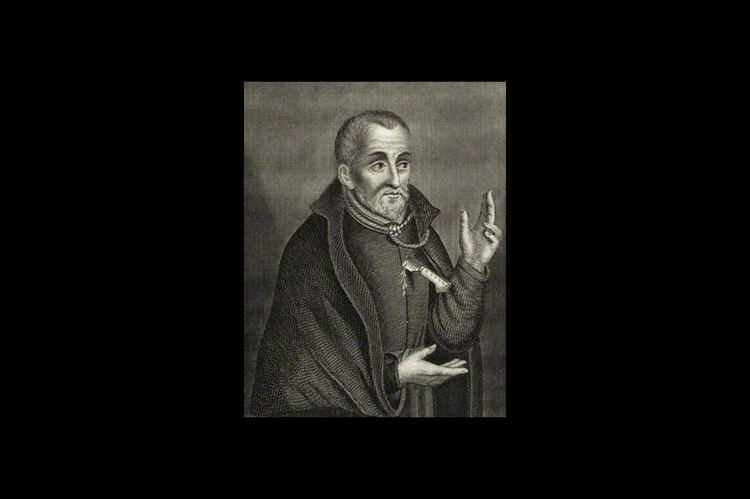

You might be wondering what any of that has to do with the Feast of St. Edmund Campion, which we celebrate today. Well, for one thing, today, Dec. 1, is also World AIDS Day. More than that, the two stories have something in common: a cause of death. I don’t mean that Edmund Campion died of AIDS or that people with AIDS were drawn and quartered. What I mean is this: What killed Edmund Campion is at its heart the same force that prematurely killed so many of those decent people: Fear. People were afraid. And they panicked. And that got people killed. Panic is the enemy of life. A healthy fear can help keep you alive. But panic will get you killed. And that’s what happened.

Looking back on both of these phenomena, we might be tempted to think that the real explanation is more complicated than that, but it isn’t. To be certain, the fear that led to the panic, which led to the scapegoating of Edmund Campion and the men and women who prematurely died in the AIDS pandemic, manifested itself in many ways. There’s a lot to study and talk about regarding both events, much that science, political and otherwise, can help to illuminate. But in the final analysis, human beings have a tendency to panic and then to kill that which we fear.

Not even our Lord escaped that simple human reality. After all, the great story of Christmas, which we prepare for this Advent season, leads to Good Friday. But it doesn’t end there. It ends on Easter Sunday, when the Lord transcends the finite bonds of time and space and triumphs over death, not just his death but ours as well.

In the incarnation, the Lord didn’t just take on a human nature but human nature itself. In his resurrection, the Lord completed not only his human journey but every human journey: St. Paul’s, Edmund Campion’s, Arthur Ash’s, Ryan White’s, yours and mine. The resurrection charges our senseless sorrows with meaning and in doing so it enjoins us not to panic, to be not afraid; to rejoice in the one who is truth. That is the truth—he is the truth—for which Edmund Campion died. St. Campion is not only then a martyr for the church or for the Lord but for you. For me.

So Simon and Garfunkel were wrong. I was never alone in that dorm room. I couldn’t be. I am a part of all that I have seen, and all that I have experienced. Not just with my own eyes but through the eyes of people of faith and goodwill across the centuries. The poet John Donne was closer to the mark. “No man is an island.... Any man’s death diminishes me/ Because I am involved in mankind/And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls/ It tolls for thee.”

Fear drives the panic that leads to intolerance still: Intolerance of the immigrant, the migrant, the poor, the marginalized.

So why is Edmund Campion the patron saint of America Media? There are lots of answers to that question, too. Here’s mine: We still live in a world where people are afraid. Our magazine is called America because when it was founded in 1909, some people were afraid of Catholics. So afraid that they told our forebears they had no place in this country. That form of an age-old fear has perhaps passed away. But others remain. Fear drives the panic that leads to intolerance still: Intolerance of the immigrant, the migrant, the poor, the marginalized. Intolerance of different points of view, of people who disagree with us, who have different worldviews. Unchecked, we know where that intolerance leads.

As a ministry of the church, America Media exists to bear witness to a different perspective, one rooted in the same reality for which Edmund Campion died, the same reality in which our forebears labored at this work. Either America, the magazine, belongs to every faithful Catholic voice or it is not Catholic. Either America, the country, belongs to all Americans or it belongs to no one.

Thus, in a world of fear and panic, America exists to echo the words of the Lord himself: Be not afraid. For in God’s time, the grace of his incarnation and resurrection is still wending its way through numberless human experiences, making them one—making us one; effecting the only change that truly lasts.

More from America

– What reporting on the AIDS epidemic taught me about my fellow LGBT Catholics

– 3 lessons the HIV/AIDS pandemic can teach us about COVID

– Dear White Catholics: It’s time to be anti-racist and leave white fragility behind.

– Six Catholics are on the Supreme Court. What they should do on death penalty cases isn’t clear—or satisfying.