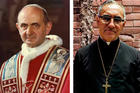

On Oct. 14 Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador will be canonized in Rome. The archbishop was assassinated on March 24, 1980, for challenging the violence and social inequalities in El Salvador. Romero’s powerful life story has been told often, especially well in Love Will Win Out by Kevin Clarke, a senior editor at America Media.

But there is a tale related to Romero that has not been told, a winding yarn that involves the legendary auteur John Huston hearing pitches in pajamas, a young Senator John Kerry feverishly working a film projector, the Federal Communications Commission as an instrument of grace and an indomitable priest, known as “The Pope of Pacific Palisades,” willing to take on Salvadoran generals and Hollywood executives to make a feature film about the martyr.

It was said of the Paulist priest Ellwood Kieser, known as Bud, that if he wanted to, he could find you anywhere in the world; and no matter who you were or what he asked of you, you would find yourself saying yes. “When Bud died, there was this list of writers who spoke—John Wells, David E. Kelley, Tom Fontana—all these extraordinary writers who had had to deal with him,” recalls the “Romero” screenwriter John Sacret Young. “And they each told essentially the same story: He would call them up, they would go, ‘Oh my God, it’s a Catholic priest calling, what does he want? No, I don’t want to do it, no, no, no; oh, I’m doing it.”

On the eve of Romero’s canonization, the film’s actors and writers look back at the seminal biopic

“He had a vision, he had a calling, and he was very firm about it,” says Lawrence Mortoff, an executive producer of “Romero.” “He was very effective as a communicator.”

Six-foot-seven-inches tall, with glasses, hearing aids and wavy light brown hair, Bud Kieser came to Los Angeles to work at St. Paul’s Parish in Westwood. Many parishioners worked in Hollywood; one, the director Jack Shea, who worked on everything from “The Bob Hope Show” to “The Jeffersons,” told him his ideas on faith belonged on television.

The result was “Insight,” a syndicated anthological television series that aired across the country for 25 years, beginning in 1960. The show offered half-hour morality plays and featured a Who’s Who of Hollywood talent, including stars like Ed Asner, Patty Duke, Walter Matthau, Martin Sheen and Cicely Tyson, and writers like Rod Serling and Michael Crichton. It won an Emmy four times out of six nominations.

“You can talk to many stars who loved their time on ‘Insight,’” notes one of Kieser’s fellow Paulist fathers, John Geaney, who also worked in communications. “‘Insight’ gave people opportunities to direct and write subject matter that the studios would just not touch,” says Michael Ray Rhodes, who collaborated with Kieser for decades as a writer, director and, on “Romero,” producer. “He made me feel I could do things, that I was capable of it. There was a kind of strengthening element to him.”

[Explore America's in-depth coverage on Oscar Romero.]

Through Eyes That Have Cried

There was another element that made the show such a lasting success: Programming in “the public interest” was required of every station by the F.C.C. Then with the Reagan administration came the argument that marketplace competition alone could fulfill the needs of the public. “Bud and I worked with four or five other people to make sure the F.C.C. kept the idea of public service alive,” Father Geaney recalls. Their lobbyist assured them they had the votes. They ended up losing 6 to 1. “The F.C.C. commissioners weren’t leveling with us. We got creamed.”

Though “Insight” was well regarded, Kieser felt the handwriting was on the wall: Without the public service requirement, stations were almost certain to start dropping the program in favor of secular moneymakers. Rather than fight the trend, Kieser decided to try his hand at movies. Father Geaney was devastated. “I was standing in the office in front of him, literally screaming at him, ‘Are you out of your mind? We have a perfectly good product.’”

Just a few years after Romero’s death, El Salvador was still a place of bulletproof vehicles, armed escorts and intense divisions between rich and poor.

But the truth was, other ideas had been pulling at Kieser. “Between the times he was producing ‘Insight,’” Mr. Rhodes remembers, “he took trips to various parts of the world where the people were really suffering. He wanted to be there; something just clicked with him. He wanted people to see this, the pain and difficulty.”

Kieser often spoke of wanting to produce a film about Dorothy Day, too; he had even met her in Rome once, and asked her. Mr. Rhodes reports: “She’d said, ‘Fine, but wait until I die.’”

After Archbishop Romero was gunned down at the conclusion of a Mass, Mr. Young sent Kieser an article, suggesting this was the kind of story Kieser wanted to tell. He begged off trying to write it himself. “Get someone who knows Central America,” Mr. Young suggested.

Two years later, though, the script Kieser commissioned had gone nowhere. He went back to Mr. Young.

“The next thing you know, I was on a plane,” he recalls.

Just a few years after Romero’s death, El Salvador was still a place of bulletproof vehicles, armed escorts and intense divisions between rich and poor. “Fear was right beside you,” Mr. Young remembers. “Not intense fear, but a leeriness, a wariness, a recognition of what can happen.”

Armed with press passes, Mr. Young and Kieser had conversations with everyone from the Jesuit Ignacio Ellacuría—“win an Oscar for Oscar,” he told them, six years before he himself would be martyred in San Salvador—to Roberto D’Aubuisson, the charismatic political leader who would later be named as the one who ordered Romero’s assassination.

Mr. Young remembers interviewing General José Guillermo García, minister of defense in the Revolutionary Government junta that ruled El Salvador at the time of the Romero assassination. He was an intimidating figure, “a bull of a build,” with “thick, heavy-veined” fingers and a military uniform decked out in ribbons. But Kieser went after him fearlessly, grilling him about what had happened and barely controlling his anger.

“I think he thought that he was safe,” says Mr. Young of Kieser. “He was American, he was big, he had press credentials, and he wanted to deliver his message.”

They traveled through villages where “whole walls were picture after picture of those who had disappeared,” Mr. Young remembers. “Then there’d be another wall of those who’d been discovered, or dead but not identified. So you’d have these images of the beaten, the bloody and the dead.”

For Mr. Young the most profound experience was visiting El Playon, an expanse of volcanic rock on which the bodies of victims were often dumped. “How darkly stunningly beautiful and awful that location was,” he says. “Because the lava bed was black, the bones of the skeletons were so white. You were sort of blinded by both the dark and the light of it.” He watched families wander among the bones, searching for the remains of a husband, a daughter, a grandson.

Builders of a Great Affirmation

Returning to the States, Mr. Young set to writing. He saw Romero as akin to Thomas More. “Romero was faced with a circumstance he didn’t want—he didn’t look for it, he didn’t like it. But the discovery was that he had to do what he did, and in some ways that was liberating.”

While getting the story made would involve many challenges, the most persistent was there from the start. “Bud Kieser wanted to pontificate,” explains Mr. Young. George Folsey, whom Kieser would bring on later to help edit the finished film, agrees. “Kieser always had the inclination to overstate his case. He was a great producer, but not a great writer. He was just too heavy-handed with all this stuff.”

Screenwriter John Sacret Young saw Romero as akin to Thomas More. “Romero was faced with a circumstance he didn’t want—he didn’t look for it, he didn’t like it.”

Kieser’s approach made it a challenge to find a director, too. “Some candidates came in, but they really wanted the freedom to do whatever they wanted to do,” explains Mr. Mortorff. “Bud wanted a director who would listen to him. It was his movie.”

Mr. Young remembers a wild morning sitting at the bedside of a sickly John Huston as Kieser wooed him. “Huston says to me, ‘How long were you in El Salvador?’” Young recalls. “‘A couple weeks.’ ‘Wow, a real veteran.’

“Meanwhile Bud is nosing me to the side and saying ‘Yeah, we know the script needs work, but they all need work. Meanwhile the story is a great story.’ And as Bud talks, Huston is starting to rise from the dead; he’s trying to sit up, his color is coming back. Bud sprayed when he talked, so there’s spittle flying and Huston is saying he’s got one more movie to do first, and I’m looking at them and thinking this is crazy, but it’s also wonderful.”

Six months later Huston was dead, but “Romero” had found John Duigan, an award-winning Australian screenwriter and director looking to come to Hollywood. “He was a great guy,” remembers Mr. Mortorff, “easygoing.”

Meanwhile, an existential question loomed: Who exactly was going to watch this picture? “Nobody [in the States] wants to see stuff that’s not set in the U.S.,” Mr. Rhodes explains. Kieser heard as much as he went to film studios trying to raise the three million dollars he needed, but eventually he convinced a friend at Warner Brothers to back him.

Even with funding, what Father Bud Kieser and his team were attempting was ridiculously difficult.

Even with funding, what Kieser and his team were attempting was ridiculously difficult: a period piece, shot on a shoestring budget in a country where English was not the local language (Mexico), with a director, cinematographer and producers who did not speak Spanish.

There was pushback from Warner Brothers about having a Mexican crew, says Mr. Rhodes. “Mexicans won’t know squat and they won’t be reliable,” the argument went. If problems occurred, Warner Brothers would probably take over the production.

But advised by a talented Mexican producer, Mr. Rhodes was able to gather an excellent group, including future Oscar-winning writer/director Alfonso Cuarón. The team gelled remarkably well. “We all became really fond of each other,” Mr. Rhodes says.

Kieser would occasionally say Mass for everyone. “He just massacred the Spanish,” remembers Rhodes. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh God, I don’t even think they can understand what you’re saying.’ But I didn’t say anything because it was something he really wanted to do.”

The actor Tony Plana remembers those Masses. “His pronunciation would make us native speakers laugh. ‘Esto es un gran pay-LEE-koo-lah’, he would say. [“This is a great MOO-vie.”] It was so gringo. But we just adored him. When my wife and I see a great movie, we still say that to each other.”

Preaching Love

While some of the cast were local, others came from the States. Mr. Plana, a Cuban-born, Jesuit-educated actor from Los Angeles, had recently completed Oliver Stone’s “Salvador,” playing a version of D’Aubuisson. He was so eager to join “Romero” as the priest who attacks the archbishop’s inaction that he cold-called Kieser. “I said, ‘I gotta get in.’ Something in me wanted to be in this film.”

The role of Romero himself went to the great Raúl Juliá. Originally from Puerto Rico, Juliá received four Tony nominations and a solid screen career, including an award-winning performance in the 1985 film “Kiss of the Spider Woman.”

“His agent said, ‘Raúl gets a hundred thousand a week,’” Mr. Mortorff recalls. “I said, ‘That’s fine, we can pay him for one week and then we need eight free weeks.’” It took over a month before the agent relented.

Where Romero was shy and bookish, actor Raul Juliá was by nature ebullient and magnetic.

There was a lot about Juliá that did not seem suited to Romero. Juliá was almost 6 feet 2 inches tall, whereas Romero was much shorter. And where Romero was shy and bookish, Juliá was by nature ebullient and magnetic; he would invite cast and crew to his bungalow for dinner, and lead them into Cuernavaca to celebrate at the end of each week. “He would say ‘Let’s go everybody,’” recalls Mr. Plana, “and we would go out to the club, have drinks, cigars, and dance until three in the morning.”

“Everyone enjoyed just being around him,” says Mr. Rhodes. “He was at one moment filling the room and at the next laughing and hanging out with somebody.” During the shoot Mr. Plana got married; Juliá hired the best mariachis in the state and performed with them.

But the differences between Juliá and Romero only added depth to the performance. “Juliá gave larger gestures to Romero,” Mr. Plana says, and a presence that spoke volumes. “It was amazing to watch how this powerful performer and this powerful spiritual leader coalesced.”

“He invested in the seriousness of this man,” says Mr. Young.

A Future Not Their Own

With a final cut in hand that was spare, meditative and raw, Kieser and Father Geaney set out to market “Romero.” There was a steep learning curve. Father Geaney remembers Juliá reading Kieser the riot act over comments he made in interviews that he had raised money from people in the pews. “Bud was trying to help people in the church realize the importance of giving. And Raúl was saying, ‘No, we need to help people realize this movie was made the same way all movies are made. This makes us sound like we’re not serious.’”

Father Geaney brought the film’s Mexican co-star Ana Alicia to a screening at Congress. As the film began, he stepped out to do some work. “The next thing I know my assistant is in front of me waving,” Father Geaney recalls. It turned out the projection equipment was new, and the technicians didn’t know how to use it. “[Senator] John Kerry was on his knees in the projection room, pulling the film through to keep it running.”

Up against competition like “Sex, Lies and Videotape,” “Uncle Buck” and “The Abyss,” “Romero” did not last long in theaters.

Eventually the screening had to be stopped. Ms. Alicia was so upset that Mr. Kerry took her and Geaney on a personal tour of the Senate, then to dinner.

After another screening, a prominent television figure affirmed Father Geaney’s worst fears about Kieser’s move into film: “’Father, that was a wonderful movie, just wonderful,’ he said. ‘When do you think we can get it on television?’”

Up against competition like “Sex, Lies and Videotape,” “Uncle Buck” and “The Abyss,” “Romero” did not last long in theaters, in some markets just a week. At the same time, some reactions were profound. Mr. Rhodes remembers a screening for critics. “We got to the end and it was dead silence.” He was devastated. “I thought, ‘Well, here it is, it’s a great movie and nobody’s going to see it.’

“Then two minutes later the room just exploded.”

Almost 40 years since Óscar Romero’s death, El Salvador continues to struggle with violence and corruption, as does much of Latin America. At the same time, where Romero was once considered radical and provocative by the leadership of the church, today the pope himself regularly echoes his ideas.

Kieser went on to make other films, “Entertaining Angels: The Dorothy Day Story,” written by John Wells and directed by Mr. Rhodes. And despite its initial box office struggles, today “Romero” stands as one of the most significant religious films of the later 20th century. Mr. Plana is regularly asked to talk about it in classes, churches and schools. “It deepened my faith in many ways,” he says. “I don’t think anyone can brush against greatness like that, spiritual power like that, and walk away unchanged.”

Says Mr. Young, who went on to create the award-winning television show “China Beach”: “It may be the film I’m most proud of.... Bud squeezed it, beat it, encouraged it, scoured it, pummeled it out of me.”

“I met Raúl a few times after the film came out,” Mr. Mortorff remembers. “He always embraced me. ‘I’m so happy we did this. I’m just so proud as a Hispanic to have made this movie.’ He didn’t live much longer.” (Juliá died in 1994 from complications after a stroke. He was just 54.)

“For me, it was life-changing,” says Mr. Rhodes. When the crowd erupted with applause at that screening, “I thought, ‘Thank you, Jesus’—but not just for getting the film made, but for what Bud did with it.”

As the shoot was wrapping, Mr. Rhodes warned Kieser to reconsider the film’s sudden, brutal ending. “I told Bud, if the hero just gets killed, that’s not a very happy story.”

“And Bud said, ‘Mike, the ending is, he lives on, in the people that he served.’”

Correction, Oct. 3: This article, which is scheduled for the print issue of October of 15, initially said that Archbishop Romero had been canonized on Oct. 14. He is due to be canonized on that date. The article also misstated that Archbishop Romero was six foot two inches tall, when the actor playing him, Raul Juliá, was that height. Also, the name of executive producer Lawrence Mortoff was initially misspelled.

Great movie review. :)

ustv

On June 12, 2011, I was ordained a priest in the American Catholic Church and asked to be sent to El Paso Texas to open a parish at the border. When my Archbishop asked me how I wanted the parish to be named, I humbly said the "Oscar Romero Parochial and Outreach Center". My apostolate has been hospital chaplaincy which has brought me to the bedside of over 11,000 patients, many of whom died as I anointed them with the Sacrament of the Sick. Many have asked me who Bishop Oscar Romero was, and it has been a privilege to tell his story. If he were alive today, he would be with me in Tornillo, Texas, protesting the incarceration of thousands of young children. His last words echo here in El Paso today: ... Think instead in the words of God. "You shall not kill". No soldier is obliged to obey an order ... contrary to the law of God. In His name... and in the name of our tormented people ... who had suffered so much ... and whose laments cry out to heaven... I implore you ... I beg you ... I order you ... Stop the repression.”

I once saw a "rough cut" of "Romero" so your article has prompted me to re-visit the pic. While I did not work on the Romero pic, I worked with many of the persons you mention: worked as a DGA assistant director for Bud Kaiser (tenacious and bold) and Mike Rhodes (dedicated and considerate) on two TV movies. It was a pleasure to work for both of them given the exigencies of budget and schedule. Was blessed to work as an A.D. with Raul Julia, playing Santana in a CBS TV movie, "The Alamo." I still remember him taking several of our crew from Del Rio, Texas into Ciudad Acuna, Mexico for a post-filming celebration. A wonderful actor and a humble man! Many years ago as a Jesuit graduate student in Film & TV production at LMU, I was able to cast Tony Plana in a student production while he was still an LMU undergraduate. Your article brought back fond memories of all. Thank you for the article.

Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador is an inspiration to bishops and cardinals worldwide.

It was a pleasure to go behind the scenes for the fine, inspiring film "Romero". For 48 years I taught high school theology. "Insight" films such as "The Crime of Innocence" and "The Late, Great God" and "17, Going on Nowhere" and many, many others, uniquely and powerfully brought the Faith explained to the hearts of the young adults. Thank you "Bud"!

As a matter of fact toward the finish of his profession everything he could make was zombie films. and Make My Essay His last film was Survival of the Dead, before that it Diary and Land of the Dead. It was 1999 when we got his last non Zombie film Bruiser, and his non zombie films were extraordinary.