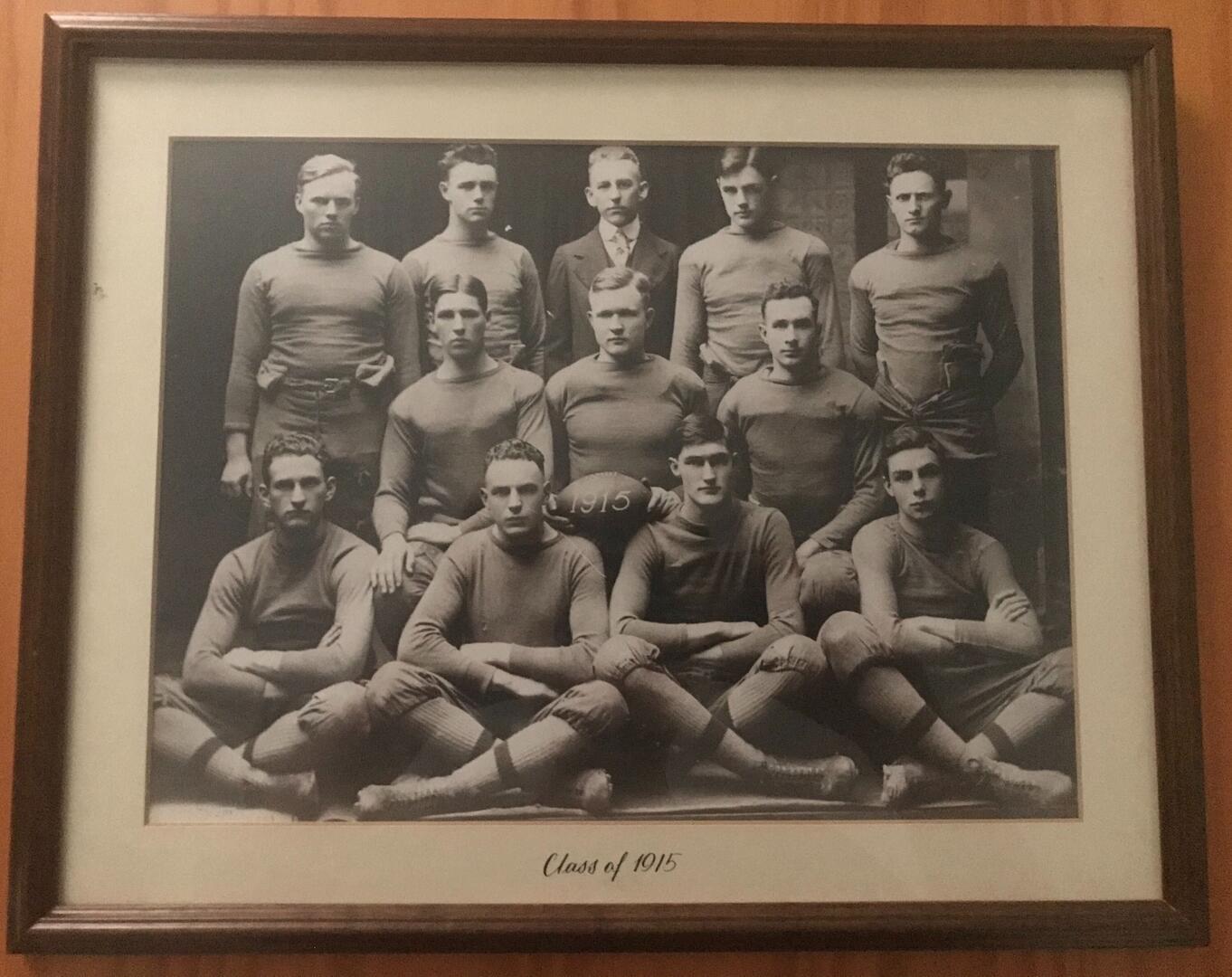

I inherited one of the few movie props in my apartment from my father, who purchased it some 30 years ago. The prop, featured in the 1989 film “Dead Poets Society,” is a framed, black-and-white photograph of an early 20th-century youth football team. In the film, the fictional English teacher John Keating (played by the brilliant Robin Williams) tells his students to listen to the photographs of pupils past. They are confused by the directive. “Carpe diem,” whispers Mr. Keating. “Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary.”

“Dead Poets Society” was one of the last films I watched with my father, James A. Di Corpo Jr., before his death from glioblastoma, an aggressive type of brain cancer, last month. He was 57. His passing came just eight months after the death of his 87-year-old mother, Shirley. But in 2020, an annus horribilis like no other, I am not alone in my feelings of grief, which come on slowly and suddenly like a mysterious disease.

The Covid-19 pandemic has now taken the lives of over 230,000 people in the United States alone. Seldom has the world suffered such mass death, such profound loss outside of wartime. While my loved ones did not die of the coronavirus, I feel great solidarity with those who have lost family members to this raging plague. And for the first time in my life, I have felt a sudden connection to a man whom I have never met: President-elect Joe Biden.

Mr. Biden spent part of the day following his Nov. 7 victory speech visiting the grave of his late son Beau, who, like my father, died young from glioblastoma. The man slated to shepherd the nation through months of collective trauma and stinging loss is no stranger to grief. Four decades prior to the loss of Beau Biden in 2015, the president-elect lost his first wife, Nelia Hunter, and his 1-year-old daughter, Naomi, in a car accident one month after his election to the U.S. Senate.

In 2020, an annus horribilis like no other, I am not alone in my feelings of grief, which come on slowly and suddenly like a mysterious disease.

Throughout his life, Mr. Biden has provided a lesson in grieving, a lesson given in full view of the public eye. The New York Review of Books has called him “the most gothic figure in American politics.” He speaks of his deceased family members at nearly every possible opportunity, including his Nov. 7 speech, when he invoked the memory of Beau. In this manner, Mr. Biden keeps those family members alive and reveals to us a difficult truth: Grieving is a lifelong process. I can clearly hear the words of my father reflecting on the death of his own father, James A. Di Corpo Sr., who succumbed to lung cancer at age 67.

“You don’t get over it. You learn to live with it,” my father said.

In the months following my grandmother’s death and leading up to my father’s death, I sought a roadmap for how to grieve, best practices for mourning the passing of loved ones. But still I have found no instruction manual on grief, no established set of rules. It is here that I think Mr. Biden can provide some insight.

Mr. Biden keeps those family members alive and reveals to us a difficult truth: Grieving is a lifelong process.

“The soul is eternity.... The soul is where you continue to live. I mean, I know my boy’s with me,” he told Oprah Winfrey in 2017. Mr. Biden’s understanding of loss is inextricably connected to his faith. “I see myself as an Irish Catholic,” he told Irish Central in 2009. Author Fintan O’Toole, writing for The New York Review of Books, notes that Mr. Biden “wears his dead son’s rosary beads around his wrist and says that litany of prayers in his dark moments.”

Turning toward the Catholic faith is, for many of us, an essential part of the grieving process. The Paschal mystery—the passion, death and resurrection of Christ—reminds us that Jesus triumphed over death and continually offers us the promise of eternal life. The “Exsultet,” sung during the Easter Vigil, states that “Christ broke the prison-bars of death and rose victorious from the underworld.” Simply put, death does not have the final say.

Both my grandmother and my father were devout Catholics. My father was briefly a seminarian in 1985, and he maintained a lifelong connection to various saints: Bernadette Soubirous, Thérèse of Lisieux and Maria Goretti. It is a hallmark of the saints that they led difficult lives and died quite young—Bernadette at 35, Thérèse at 24 and Maria at just 11. These models of sanctity taught my father the importance of a life well lived and formed his view of human suffering. For him, suffering was not something to be avoided but embraced for its redemptive qualities.

“All this is evidence that God’s judgment is right, and as a result you will be counted worthy of the kingdom of God, for which you are suffering” (2 Thess 1:5).

I have no doubt that my family members, even in their sufferings, died comforted by the knowledge that Christ would not abandon them nor the family members they left behind. In moments when grief rolls like a noxious wave, I find myself turning toward Christ’s message of salvation and again to that framed photograph of young men long gone.

Carpe diem, they say. Make your lives extraordinary.

More from America: