How does a Catholic priest minister in a town famous for its devotion to the occult? Well, first you try to be a good neighbor.

“We open the church, we invite people in, we allow them to use our bathrooms, get a bottle of water and just sit and pray,” the Rev. Robert Murray, pastor of Mary, Queen of the Apostles Parish, located in the heart of Salem, Mass., told America.

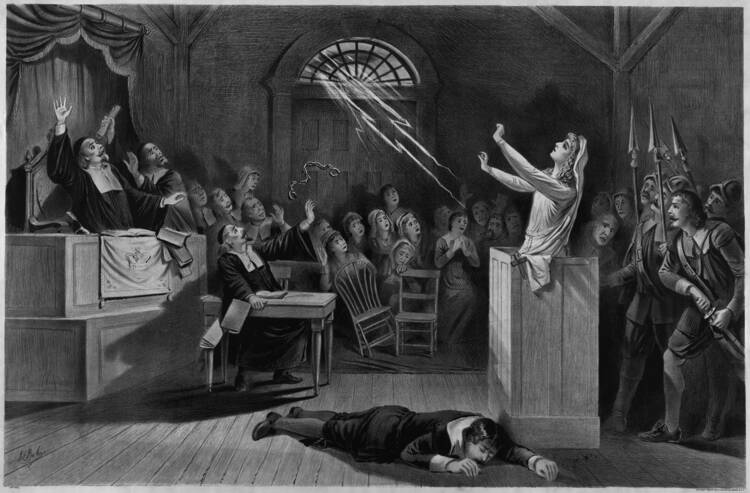

Salem, of course, is today synonymous with witchcraft, owing to its infamous history in executing people accused of being witches in the late 17th century.

One of the two churches that comprise Father Murray’s parish, Immaculate Conception Church, sits less than a two-minute walk from the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, a small park that houses locust trees, “which are thought to be the type of tree that may have been used for the hangings” of 20 people executed for witchcraft in 1692, according to the memorial’s website.

How does a Catholic priest minister in a town famous for its devotion to the occult? Well, first you try to be a good neighbor.

The history of the Salem witch trials is well-known to individuals with a solid grasp of colonial-era history. (At least, it is to me. Having grown up about 35 miles from Salem, I read about the trials, it seemed, in school every October. When I questioned my Midwestern friends during a gathering in Chicago over the weekend about the details of the witch trials, they looked at me like I was nuts.)

So for those who did not read “The Crucible” year after year, here is a brief breakdown of what went down in Salem.

More than 200 individuals were imprisoned—and, as mentioned earlier, roughly 20 women and men were executed—by authorities over a span of four months in 1692 for their alleged involvement in witchcraft. The witch hunt began when four young girls played fortune telling games with Tituba, an enslaved woman from the West Indies owned by Salem’s minister, the Rev. Samuel Parris. When the girls soon after exhibited unusual physical maladies, a physician claimed they were “bewitched.” The four girls accused others of being witches, including Tituba and other marginalized residents, and eventually, prominent residents of the area were also accused.

After some initial embarrassment about the witch hangings, the city of about 45,000 people eventually came to embrace its history. Nicknamed by some “the Witch City,” Salem includes images of witches on its emergency services vehicles, its high school mascot is a witch, and Salem is home to more than its fair share of stores promoting the occult. Hundreds of thousands of visitors descend upon Salem each fall, taking in the magic shows, mock witch trials and this year, a special outdoor screening of “Hocus Pocus 2,” set, of course, in Salem. (Even if it was actually filmed in another colonial-era city, Providence, R.I.)

Father Murray said that most visitors to Salem seem to view witchcraft in a spirit that feels more tongue-in-cheek than serious. But interest in the occult is growing, with some estimates claiming that as many as two million Americans identify as Wiccan or pagan. Some undoubtedly view Salem as a spiritual place. Last year, Boston Magazine reported that Salem is home to a disproportionately high number of people who say they practice earth-based spiritualities. The city is also home to The Satanic Temple, which opened its doors in 2016 and courts controversy around the country, mostly for its Satanic art, its trolling of the religious right and its promotion of Black Masses.

Over the years, there have been efforts by some religious groups to call attention to Christianity’s condemnation of witchcraft and the occult.

For Father Murray, welcoming people from across the world presents an opportunity for a more quiet kind of evangelization, one focused on hospitality and presence.

In 1992, Christian activists staged a rock concert in Salem to offer an alternative to the focus on witchcraft. A group of evangelical pastors and seminary students raised $10,000 in 2000 to support a “Holy Happenings” week, in which they hosted discussions and distributed pamphlets discouraging participation in the occult, the Religion News Service reported. More recently, a journalist who chronicles witchcraft wrote that evangelical protests against pagan gatherings have increased around the country.

But for Father Murray, welcoming people from across the world presents an opportunity for a more quiet kind of evangelization, one focused on hospitality and presence. The doors of the church remain unlocked, inviting visitors “to take a minute, a respite, from what is a very noisy experience” outside, he said. Parishioners stick around inside, available to answer questions, and also to pray for the safety of tourists and first responders.

For his part, Father Murray says he does not hear too often from parishioners concerned about the effect of the town’s focus on witchcraft on children, though he sometimes sees people among the crowds sporting shirts emblazoned with anti-Christian messages. And he does think Catholics should stay away from the occult, including seances, tarot cards and ouija boards. Mostly, however, he and other Catholic residents of Salem “recognize that this is a commercial enterprise,” one in which the parish is happy to participate.

[Explainer: What Catholics need to know about Ouija boards]

Witchcraft tourism brings about $140 million to Salem each year and in addition to offering a quiet place to escape some of the crowd, Father Murray said the parish also “takes advantage of the economic fruit of the month, in that we rent out our parking spaces throughout the week and on the weekends when we don’t have services,” he said. “So that actually becomes a wonderful thing for us to help out the parish financially.”