After years of grueling testimony about the treatment of First Nations and other Indigenous children in residential boarding schools during the 19th and early 20th centuries, Canadians could be forgiven if they believed they had already heard the worst. But on May 27, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced that a land survey using ground-penetrating radar at the site of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia discovered the remains of 215 children—and more are expected to be found after another survey this month.

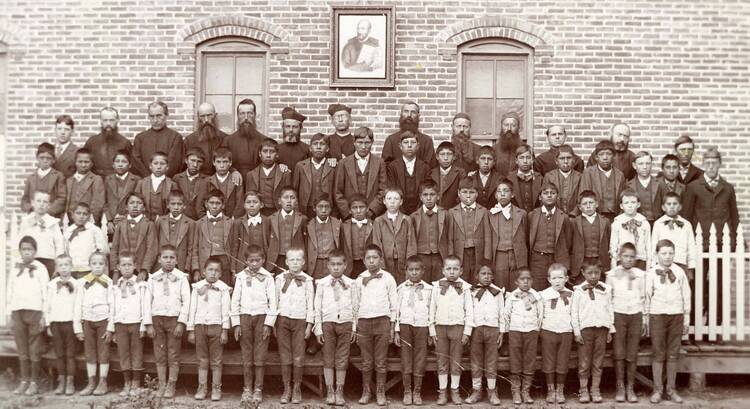

The school at Kamloops had been part of a national network of 130 residential schools that between 1883 and 1996 housed as many as 150,000 Indigenous children taken away from their families. The residential system was intended to suppress Indigenous culture and force Indigenous assimilation into Canadian society, and it frequently did so in an exceptionally brutal manner.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission spent years exploring the dismal history at these church-run schools, eventually concluding in 2015 that the residential schools represented a program of “cultural genocide.” This latest revelation and the fact that there is little clear explanation for the cause of death of the children buried at Kamloops have prompted calls for a new national investigation.

Saddened, but not surprised

While the discovery of the burials came as a shock to the general public, it was “not news” to Native American people in the United States, said Maka Black Elk.

“We are saddened by the loss,” he said. “We hurt for the ancestors in Canada who never got to know where their children were, and we want this to be an opportunity for something to be different.” But, he added, “the fundamental reality of children dying at these boarding schools is not a new story.”

Maka Black Elk: “We do believe that this work is sacramental. When we seek reconciliation, the first thing we do is bear our sins before God. That’s what we have to do.”

A chairperson of the American Indian Catholic Schools Network, Mr. Black Elk is the executive director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, S.D., a former Jesuit-run Indian boarding school. He believes it is likely that similarly informal and unmarked burials will be found among the boarding schools maintained for Native American children on the U.S. side of the border, should a substantial effort be made to look for them. After all, he pointed out, the Canadian system was modeled on the 19th-century network of boarding schools in the United States.

In fact, some of those graves have already been uncovered at the now-infamous United States Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa., and other sites, using the same ground-penetrating radar deployed at Kamloops. U.S. researchers, he said, “have worked for years now on repatriating children’s remains from [boarding school] cemeteries and doing the work of identifying them.”

As many as 6,000 Indigenous children died far from home in the residential schools, according to an initial estimate from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Many now suspect the true toll will prove to be much higher.

Often little explanation was offered to family members of deceased children. Archival analysis and survivor testimony suggest that school administrators preferred to conduct burials on site rather than accept the expense of returning the remains of the Indigenous children to their families and home communities.

The commission devoted six years to a review of the history and context of the residential schools and the treatment of First Nations’ children and issued its findings with a national call to action in 2015. That kind of comprehensive national examination of conscience “still needs to happen” in the United States, said Mr. Black Elk. Though few people know much about the history, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition reports that “hundreds of thousands” of Indigenous children attended 367 boarding schools in 27 states; 84 of them were run by Catholic religious orders.

Maka Black Elk: “We are saddened by the loss. We hurt for the ancestors in Canada,” but “the fundamental reality of children dying at these boarding schools is not a new story.”

Most Native American boarding schools that survived into the late 1960s by that time had experienced a radical shift in perspective and curriculum. The Jesuits’ Holy Rosary Mission School at Pine Ridge became Red Cloud School, for example, and began efforts to preserve Lakota culture, beginning with language restoration efforts that continue to this day. It is the only one of the four residential schools for Indigenous children managed by the Jesuits that is still in operation.

Like a few other surviving institutions, Red Cloud began its own effort to explore the past last August.

A U.S. ‘Truth and Healing’ Commission?

Brad Held, S.J., is the pastor of Holy Rosary Mission on the Pine Ridge Reservation and previously taught at the Red Cloud school. South Africa and Canada had their truth and reconciliation commissions, but “we’ve kind of gone with ‘truth and healing,’” he said, “because as we talked about the word reconciliation...this idea surfaced that reconciliation presumed a first, good relationship that one is seeking to return to. When we celebrate the Sacrament of Reconciliation it’s a ‘returning to.’”

But considering the relationship of the church, the U.S. government and the people of the United States to Native Americans, he asked, “Was there a good relationship to return to?”

Healing seemed a better word to use, said Father Held, allowing all parties to the effort to consider the possibilities of forging something new out of a struggle with the past.

Truth and Healing at Red Cloud will follow a four-stage process: confrontation, understanding, healing and transformation. Participants are still engaged in the “confrontation” phase with the history of the Indigenous experience at Pine Ridge at the Jesuit school.

The absence of a national structure to uncover the past remains a troubling challenge. The effort to find out more about the historical experience at the U.S. schools so far has been “patchwork.”

Though the process derives from Native American culture and scholarship, as a Lakota who is also a Catholic, Mr. Black Elk said he perceives “some beautiful parallels” with Catholic spirituality. “We do believe that this work is sacramental,” he said. “When we seek reconciliation, the first thing we do is bear our sins before God. That’s what we have to do.”

The absence of a national structure to uncover the past remains a troubling challenge. He described the effort to find out more about the historical experience at the U.S. schools so far as “patchwork.” There have been unsuccessful efforts to push legislation for a national commission through Congress.

But while waiting for Congress to act, Mr. Black Elk believes the U.S. Catholic Church “could absolutely step in” and provide resources to begin its own nationwide process. Mr. Black Elk in fact made a presentation to representatives of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops on June 9 to discuss the truth and healing work at Red Cloud and his hope that the U.S. Catholic church may be finally willing to begin—and fund—its own examination of conscience.

Even among fellow Jesuits, Father Held suspects, “there’s probably a great ignorance...of this history.”

“You cannot talk about the Indian boarding school period,” Mr. Black Elk said, “without also talking about the way clergy sexual abuse happened there as well. Those are uniquely tied together.”

“You cannot talk about the Indian boarding school period,” Mr. Black Elk said, “without also talking about the way clergy sexual abuse happened there as well. Those are uniquely tied together.”

When the sexual abuse crisis became national news in 2002, he added, “here in Indian country, it was very much connected to the boarding school. And…there are survivor stories of that here [at Red Cloud].

“My hope is that the church learned its lesson from the previous iteration, in terms of how it responded to, certainly, Boston and afterwards,” he said. “The response shouldn’t be to run away. It should be to confront this head on.”

Confronting the past

To that end, he suggests, the Canadian church should be more forthcoming in efforts to open historical archives and share records that may shed light on what happened to the deceased children at Kamloops and other residential schools.

“In the spirit of confrontation, you have to face this history and be transparent about it,” he said. “And that includes things like the opening of, the studying of, and the communicating of what those records say.”

Getting to that truth has become something of a race against time. Many of the last survivors from some of the worst years at the boarding schools are in their 90s today.

In the United States, getting to that truth has become something of a race against time. Many of the last survivors from some of the worst years at the boarding schools are in their 90s today. That is part of the reason the establishment of a national commission is so urgent, Mr. Black Elk said.

What he has learned so far from the experience at Red Cloud is that uncovering the past has to remain a patient process. “One of the things that I think is important to know is healing doesn’t happen until much later in this process,” Mr. Black Elk said. “For some people, there’s often a desire to dive directly into healing as soon as possible. But that’s not how we truly achieve healing. We have to do these harder things first.”

One of the harder things for Father Held is trying to comprehend the mentality of his predecessors at Pine Ridge, especially as he learns more of how Indigenous children were treated and the unchallenged antipathy toward Indigenous culture. He has come to marvel at “how the church can get tied up in the society in which it lives.”

His view now is that the church and the people of God, especially church religious leaders, did not transform the society they inhabited as much as they were transformed by it, uncritically accepting notions like Manifest Destiny and embracing slogans like “kill the Indian, save the man,” deployed by General Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

“It is a sin of a failure to live the Gospel and of being caught up in political ideas of a time that were destructive,” Father Held said.

So much attention is paid by the church to inculturation of Native Americans, Mr. Black Elk said—“how they bring their gifts to the church, how they continue to transform themselves to be their best selves, without changing who they are.”

Why is that degree of self-reflection not demanded of the mainstream U.S. Catholic community—the community that failed Native American children, he asked?. “People failed then not just to live by today’s standards, they failed to live by Gospel standards…to live up to what the faith calls people to.”

That failure has to be acknowledged, he said.

“I think that’s an important part of healing,” Mr. Black Elk said. “It’s much bigger than individual [Native American] survivors overcoming their own trauma. Yes, that’s core and important, but healing in this case is for everyone, including those who inherit the legacy of the perpetrator.

“Healing has to happen there, too.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article appeared under the headline: “A mass grave for Indigenous children was found in Canada. Could it happen in the United States?” It has been updated to refer to the discovery as a ‘burial site’ not a ‘mass grave.’