This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

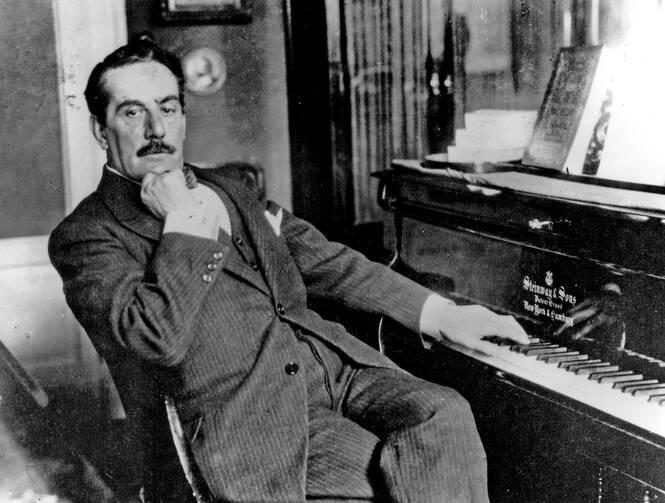

What are we to make of the life, music and spiritual beliefs of Giacomo Puccini, the composer said to be responsible for fully one quarter of all opera performances in the United States today?

Puccini, who died a century ago on Nov. 29, 1924, has been called the world’s most popular songwriter, notwithstanding his modern heirs and successors, and with good reason. In a 10-year burst of creativity at the turn of the 20th century, the Tuscan maestro turned out “Manon Lescaut,” “La Bohème,” “Tosca” and “Madama Butterfly,” any one of which would have conclusively made his reputation.

Puccini’smarriage of thrilling melodies and shamelessly sentimental climaxes, sumptuous orchestrations and universal human stories—with dramatis personae including poor Parisian bohemians, Wild West cowboys and Chinese princesses, among many others—has long since made him a titan of his field, with a power to move millions of ordinary men, women and children who would never normally go near a gilded opera house.

These things are necessarily subjective, but anyone doubting the merits of Puccini’s claim to be the people’s composer might wish to recall Luciano Pavarotti’s performance of “Nessun Dorma” for spellbound audiences at the 1990 soccer World Cup. Or to revisit “Madama Butterfly,” and more specifically the scene in which the title character presents the U.S. consul in Nagasaki with the love child she has borne with the faithless American naval lieutenant she has fondly believed to be her soon-to-return husband. “And this? Can he forget this as well?” she cries, brandishing the infant aloft. It’s one of the most arresting moments in all opera, and a cri de coeur on behalf of every woman ever abandoned by a feckless man.

The lieutenant does return, albeit with a new American wife. Butterfly’s greeting to her—“Under the great dome of heaven, there is no happier woman than you, and may you always be so”—is sublime, an act of forgiveness almost too deep for tears. The opera is a tragedy in anyone’s terms, but one with the supremely redeeming theme of man’s, or woman’s, capacity for mercy, and in that sense the most spiritually uplifting moment of all Puccini’s works. “Madama Butterfly” continues to arouse debate about its moral and ethical complexities in today’s changed geopolitical climate, but surely its true message is that of the resilience of the human heart and our ability to display the divine spark of compassion.

Over the years, critics have interpreted Puccini’s works in a Freudian key, making much of the themes of unrequited love, suffering and death that seem to follow from certain events of the composer’s own life. Or, failing that, he has been placed as the central character of a still continuing debate about the rights or wrongs of cultural appropriation. The historian Alexandra Wilson has even written a well-received book titled The Puccini Problem, in which she explores the “wide range of extra-musical controversies concerning such issues as gender and class” provoked by his work.

Missing from all this is the surely central ingredient of Puccini’s life, or for that matter of any individual responsible for a truly worthwhile piece of art—that of his own relationship with his Maker.

Touched by the Almighty

Puccini may not have been known either for his church attendance or for his overtly religious canon, but there is ample evidence that he felt God to be close at hand at critical moments of his life. The composer once said that “The Almighty touched me with his little finger and said: ‘Write for the theatre—mind, only for the theatre.’ And I have obeyed the supreme command.”

Since Puccini wasn’t as a rule one to speak of such epiphanies, we should take him at his word. Spirituality still informed his work toward the end of his life, 40 years later, in “Suor Angelica,” his one-act opera set in a convent, with its consoling message of divine forgiveness and of the ultimate reunion of the living and the dead.

Or consider his earlier opera, “La Fanciulla del West”—the work Puccini himself always considered his greatest achievement as a composer—at whose climax Minnie, the local saloon owner, persuades a mob of hardened Gold Rush miners to spare the life of a captured Mexican bandit on the grounds that there is no one on the face of the earth who cannot be redeemed by the power of love. After some theological discourse on the subject, the bandit is set free by the same men who minutes earlier were eager to hang him, a reprieve he acknowledges by a heartfelt “Grazie, fratelli”—an evocation of universal brotherhood that raises the whole story above the level of a mere gangster melodrama.

Or there’s “Tosca,” Puccini’s opera set against the backdrop of Napoleonic revolutionary fervor and the struggle for Italian independence. It’s a story that’s equal parts historical epic, tragic romance and musical tour de force. Puccini and his librettist, Luigi Illica, ensured that a statue of St. Michael the Archangel, one of God’s principal agents in the battle fought in heaven against Lucifer and his agents, be prominently displayed on stage. Tosca herself, faced with a series of emotional crises, repeatedly addresses her Creator as “Signor,” not “Dio,” speaking to him as a friend as much as a deity, a reminder that Puccini saw the essential story not only for its romantic and tragic aspects, but for its spiritual qualities as well.

Similarly, Puccini’s unfinished 1924 masterpiece “Turandot”contains certain unmistakable biblical allusions and allegorical insights into the composer’s spiritual beliefs, not least in its rousing aria “Nessun Dorma.” In one of those faintly convoluted plot developments familiar from any great opera, the character Calàf has given Princess Turandot one last chance to kill him instead of marrying him if she can discover his name before morning. Turandot pursues this task fruitlessly through the night, and Calàf ends the aria by declaring both his desolation and his confidence in ultimate victory, an echo of the Lamentations service traditionally associated with Holy Saturday. For that matter, the whole narrative device of a long, nocturnal vigil prior to a journey down a perilous but unalterable track, toward a destination boldly stated, resonates with the synoptic accounts found in Mt 26:36 and Mk 14:32.

Not only do parts of “Turandot” stir the heart and soul; they also reflect the particular mysteries contained in the account of our Lord’s passion. As often noted by its critics, “Turandot” may be illogical and at times hopelessly overblown. But it makes perfect linear sense as a parable of suffering and ultimate redemption. I am always struck by the harrowing words uttered by the slave girl Liù, as she refuses to divulge the name of her prince even under torture, assuring her tormentor:

You who are girdled with ice

Once conquered by so much flame

You will love Him too!

Before this dawn

I will close my weary eyes

So that He may still win!

He may still win!

The words are Puccini’s own.

A Lonely Hunter

Humanity being fallen, it should come as no surprise to learn that Puccini’s own life at times failed to match the pristine beauty exemplified by his music. By 1903, the already widely acclaimed and fabulously wealthy composer had for the previous 17 years been conducting a non-exclusive affair with Elvira Bonturi, the wife of an old school friend.

In due course, Elvira bore Puccini a son, but the couple were unable to marry and legitimize the boy because divorce was not possible in the Italy of the time. The situation may well have suited the composer, who then described himself as a “hunter of wild fowl, operatic librettos and attractive women,” the most prominent of whom was a young schoolteacher whom he nicknamed “Corinna.”

On Feb. 25 of that year, fate took a strange turn. Puccini, by then at work on “Madama Butterfly,” suffered a serious automobile accident when, near Lucca, his chauffeur-driven car plunged off the road. The composer was found pinned underneath the car, almost asphyxiated by gasoline fumes and with his right leg broken. He would clearly need someone at home to care for him.

And by another twist that seemed almost operatic in its implausibility, the very next day Elvira became a widow. Her husband Narisco died after being assaulted by the enraged husband of one of his own numerous mistresses, leaving her free to marry Puccini. This concluded matters with Corinna, who the composer discovered had strayed from the monogamous demands he placed on all his partners, while not accepting any reciprocal obligation on his part.

“What an abyss of depravity and prostitution!” he wrote to her, bringing an end to their relationship. “You are a s—, and with this I leave you to your future.” Puccini and Elvira remained married for the remaining 20 years of his life.

The successive drama of the car wreck, Elvira’s widowhood and the acrimonious split with Corinna may well have spurred the composer’s most powerfully tragic music in the form of the last act of “Madama Butterfly.” Further melodramatic developments were to follow.

In July 1909, Elvira Puccini was sentenced to five months’ imprisonment. She had been found guilty of what would today be called harassment, in a case as tragic as any story her husband or his librettist might have contrived on the stage. A 23-year-old woman named Doria Manfredi had for several years worked as a maid in the Puccini household. By all accounts she was devoted to the family, but in 1908, Elvira, who was subject to wild fits of jealousy, publicly accused the woman of carrying on an affair with her husband. Despite denials on all sides, Elvira pursued the maid with letters and threats.

Although Elvira was often right to be suspicious of her husband, it later emerged that she was tragically mistaken in this case. In January 1909, Doria, consumed with shame at the scandal surrounding her name, committed suicide by drinking poison.

Nearly a century later, documents found in the possession of one of the dead woman’s descendants, Nadia Manfredi, revealed that Puccini had actually been conducting an affair with one Giulia Manfredi, Doria’s cousin. Doria had simply been acting as a go-between, carrying letters to and from the furtive lovers.

‘So I Am Made’

Even from the start, Puccini’s ability to create music that captured the essence of the human experience, from the soaring melodies of his love duets to the wrenching arias of their despair, was what most distinguished him from his contemporaries. It does not stretch credulity to suggest that the composer’s final opera, “Turandot,” is infused with a critical ingredient that in part stemmed from the Doria Manfredi tragedy, one that would be instantly recognized by the observant Roman Catholics among his audiences—namely, a sense of guilt, but the sort of guilt that, far from denying us the prospect of redemption, encourages us to acknowledge our fallen nature and to pray for our forgiveness.

As Puccini himself said: “I have always carried with me a large bundle of melancholy. So I am made.” “Turandot” dares to shun much of the lush romanticism that had so endeared Puccini to audiences earlier in his career. It is a postmodern love story. Its unlikable twin leads go largely unfazed by the death and dislocation they instigate; when they finally share true love’s kiss, they’re standing atop a figurative pile of corpses. I would suggest that this is the work of a man assessing his prior life and finding it wanting, embracing his shame and at last willing to leave his moral comfort zone and be led to a place where he can more profoundly contemplate his own nature and, more importantly, his relationship with his Maker.

Puccini himself did not live to see his final opera’s opening night. In late October 1924, the composer had gone to Brussels to seek treatment for what he believed to be an infection, but was in fact terminal throat cancer. While there, he made the acquaintance of Cardinal Clemente Micara, the prelate who then served as papal nuncio to Belgium and later as vicar general of Rome. An immediate friendship began, and the two met every day, sometimes several times a day, for the brief remainder of Puccini’s life.

Here is how the cardinal remembered the events of Nov. 29, 1924:

I had just finished celebrating Mass when I received an urgent message from the Mother Superior of the hospital where Puccini lay ill. She asked me to come immediately. I was moved by Giacomo’s appearance when I reached his bedside. During the night he had had a heart attack, and the doctors had informed his relatives that there was no longer any hope.

I gave the maestro the comforts of religion, and his last sign of consciousness was to show that he was aware of what was happening, and was relieved by it. When the end came it was without excessive pain, quiet and serene. He died that same morning at 11.30.

Puccini was given a state funeral, paid for by the Italian government, in Brussels, before his body was borne back to be interred with full Catholic honors in Milan. The composer had taken a briefcase with him on his final journey to Belgium, and this was found to be full of notes for the climactic duet between Princess Turandot and Calàf, a scene he intended to represent “the final triumph of divine love over cruelty and death.”

Correction, Nov. 12: This article has been updated to remove a reference to a deathbed scene in “Tosca.” The title character died after jumping off Castel Gandolfo.