This summer marks the 100th anniversary of the Scopes Trial.

On July 21, 1925, a jury in Dayton, Tenn., convicted John Scopes, a high school science teacher, of violating the state’s Butler Act, which forbade the teaching of biological evolution in public schools.

The Scopes trial has long been depicted as a clash between modern science and religious fundamentalism, with academic freedom as the victim. There is some truth in this interpretation, especially in an American society where religious truths and biological truths are routinely confused with each other. But the Scopes trial was also a chapter in the eugenic racism that had become a creed of social elites in the early 20th century.

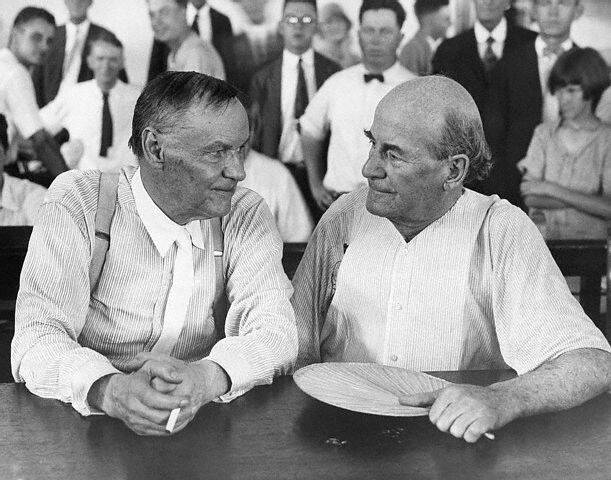

The Scopes trial was a show trial, instigated by the American Civil Liberties Union in an effort (ultimately unsuccessful) to have the courts declare the law banning the teaching of evolution unconstitutional. Supported by the A.C.L.U., Scopes encouraged his students to testify that he had indeed defended Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the classroom. The international publicity for the trial was enhanced by the presence of stellar gladiators for the prosecution and defense. Former Secretary of State and three-time Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan spoke for the prosecution while the militant agnostic and political radical Clarence Darrow argued for the defense.

The evolutionary theory defended by Scopes was not limited to biology; it claimed that some members of the human species were more evolved than others and that the state had the duty to promote the more evolved members and to repress the less evolved.

In this social Darwinism framework, “survival of the fittest” was no longer just a biological drive that explained why some species of flora and fauna thrived while others declined; it was now a moral norm that would guide the state in purifying the population pool. Indeed, Bryan’s opposition to the teaching of evolution was partly grounded in the theory’s religious and social consequences. A political progressive and evangelical Christian, Bryan described evolution as “the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak.”

Fruits of this social Darwinism in the 1920s included the 1924 Immigration Act, which mandated quotas that privileged white Protestant immigration (especially from “Nordic” countries), and the compulsory sterilization laws targeting the “unfit,” which the Supreme Court declared constitutional in the 1927 Buck v. Bell decision.

Ironically, at the time of the trial, public school teachers, including John Scopes, were required to use George Hunter’s textbook Civic Biology: Presented in Problems, which included a favorable description of Darwin’s theory of evolution. But it was also an exemplar of social Darwinism in all its eugenic racist fervor. Civic Biology claimed that there were five human races and that they were not equal in intellectual stature.

There exist five races or varieties of men…. These are the Ethiopian or Negro type, originating in Africa; the Malay or brown race, from the islands of the Pacific; the American Indian; the Mongolian or yellow race, including the natives of China, Japan, and the Eskimos; and finally, the highest types of all, the Caucasians, represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America.

Unsurprisingly, Hunter strongly supported racial segregation in schools and opposed interracial marriage. Scopes and his colleagues were informing their Tennessee students that the segregated classrooms in which they met had a “scientific” justification since Black students could only be trained for manual labor while white students would pursue more intellectual subjects. To oppose such racism was to oppose the march of evolutionary progress.

Hunter also supported the forced sterilization of those deemed unfit to reproduce due to physical or mental disorders or to criminal behavior or simple sloth. He considered these people nothing but social parasites who should be prevented from procreation:

Hundreds of families spread disease, immorality, and crime to all parts of this country. The cost to society of such families is very severe. Just as certain animals or plants become parasitic on other plants and animals, these families have become parasitic on society. They not only do harm to others by corrupting, stealing, or spreading disease, but they are actually protected and cared for by the state out of public money…. They take from society, but they give nothing in return. They are true parasites.

In this perspective, the disabled and the unemployed are to be disdained as burdensome anomalies in the march of progress. For Hunter, social welfare programs are dangerous since they retard the evolution of society by their expensive care for the “unfit.”

At the time of the Scopes trial, the same state of Tennessee, which banned the teaching of Darwinian evolution in its Butler Act, mandated the teaching of Darwinian evolution—in Hunter’s version—in all public high schools through its Board of Education. Giving a scientific veneer to racism was one thing; challenging the literal meaning of the Book of Genesis was another.

The centennial of the Scopes trial is a moment to revisit the complicated dialogues between religion and science. But it is also the moment to remember the thousands of our fellow citizens who were sterilized against their will or denied an education in the name of a certain version of evolutionary science.