In 1976, David Driskell took on the monumental task of mounting “Two Centuries of African American Art.” First displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art before traveling across the country to Dallas, Atlanta and New York, the show presented a cross section of art made by Black people in America. A new HBO documentary, “Black Art: In the Absence of Light,” looks at the legacy of Driskell (1931-2020), a Black American scholar, artist and curator, and his revolutionary landmark exhibition.

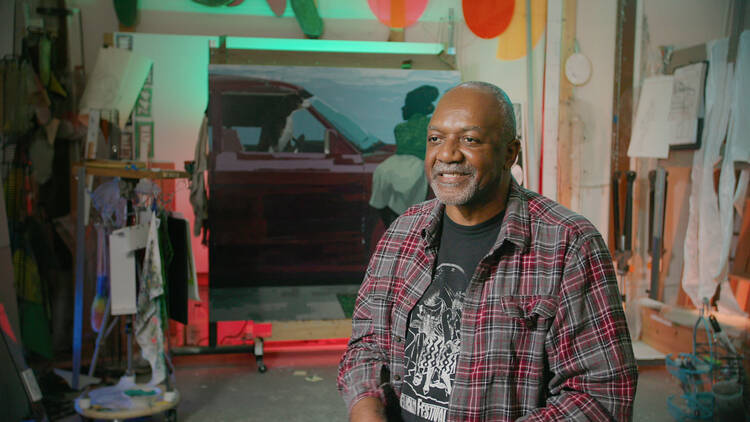

Weaving together interviews with major contemporary artists, curators, art historians, collectors and Driskell himself, the documentary contextualizes the history and power of Black art in America. “Black is not the absence of color. Black is a particular color,” the artist Kerry James Marshall tells us, sitting in his studio. The particularity of Blackness as it pertains to art is the backbone of this documentary. Where the documentary shines is in its ability to carefully illustrate the interconnectivity of Black artists working in America.

The particularity of Blackness as it pertains to art is the backbone of this documentary.

Driskell asserts that Marshall has “all but redefined the whole concept of what Black art is about” by concentrating on just the Black subject. But Marshall does not just pop up out of nowhere. He evolves out of a particular lineage influenced by Black artists, writers and thinkers before him.

Marshall tells us about replicating compositions from Charles White’s book Images of Dignity in his youth. We hear about him taking classes with Betye Saar as a teenager at Otis College of Art and Design. The silhouetted figure in Saar’s 1969 “Black Girl’s Window” stares back at us before we begin to consider Marshall’s 1980 “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self.” The black on black painting—with bright pops of white for the teeth and eyes—deals conceptually with themes of identity at play in Ralph Elison’s Invisible Man and marks a turning point in Marshall’s practice.

“Black is not the absence of color. Black is a particular color,” the artist Kerry James Marshall tells us.

From this point on we see the emergence of desaturated flesh in Marshall’s paintings. He renders Black bodies in grayscale using seven different black pigments that, when layered like an Ad Reinhardtcolor field painting, create a depth in which you can almost swim. His figures are “unequivocally, emphatically Black” and exist in the everyday, in barber shops, art studios, playgrounds and living rooms. “He popularized the ordinary,” Driskell tells us. “We see ourselves in so many different ways.”

In 2016 the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry,” a retrospective of the artist’s work. I was lucky enough to sneak away and visit the exhibition during a lunch break while working in construction around the corner. I only now realize how much of an impact it had on my own artistic practice at the time, as I explored themes of class, labor, identity and the body through figurative drawings. Marshall’s work has been centered in the art world in recent years in a way that would have been unimaginable in 1976.

In 2018, Black art captured the nation’s attention with the unveiling of the Obama portraits.

Just two years later, Black art captured the nation’s attention with the unveiling of the Obama portraits. Kehinde Wiley’s hip-hop influenced old master aesthetic now takes center stage in the Hall of Presidents in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., while Amy Sherald’s striking portrait of Michelle Obama created a viral moment that inspired a children’s book.

In one of the documentary’s most endearing moments, Sherald—a relative unknown before painting Mrs. Obama—is asked what that commission meant to her: “I’m relieved I can pay off my school loans.” Using a paper plate as a palette, she creates new paintings that catapult her to the forefront of the contemporary art world. Seeing her paintings of fleshtones rendered in bluish charcoal grays, the viewer might find it hard not to think about how Marshall’s mastery has affected her own. She exists in the lineage of Marshall and Saar, Driskell and White.

Speaking about the current gold rush in the market for Black artists, Sherald says she hopes it is because “we are making some of the best, most relevant work,” but the reality seems more complicated than that. Swizz Beatz—the musician, producer and mega collector husband of Alicia Keys—explains collecting to us. In his home gallery he handles a Hank Willis Thomas basketball, inscribed with “All Lives Matter” but with the “V” cleverly absent. On the screen we see images of Beyonce and Jay-Z filming in the Louvre and a headline revealing P. Diddy as the buyer of a $21 million painting by Kerry James Marshall.

This current gold rush is not by chance. It is the product of the labor of countless artists and historians, curators and collectors working to make Black art visible and valued over the course of the last two and half centuries. “Black Art: In the Absence of Light” puts faces and names to so many of those people, far more than I could discuss here. It is certainly worth a watch.

More from America: