On June 22, 1986, four years after the end of the Falklands War, in which Argentina had tried and failed to reclaim territories off the Patagonian coast from the British (who had been occupying them since the 19th century), the two countries faced each other on a soccer field in Mexico. With only four countries left competing for the World Cup, this face-off seemed almost destined to happen. The pain of the short, but deadly, conflict fresh in the minds of Argentineans meant that there could be only one acceptable outcome: Argentina had to win this time, even if it meant God had to have a hand in it.

Six minutes into the second half, 25-year-old Diego Armando Maradona scored a controversial goal that is still among the most miraculous moments in soccer history. Determined to score, the 5-foot-8 Argentinean David took on his Goliath, the 6-foot-1 English goalkeeper Peter Shilton, and, after committing an infringement (he touched the ball with his hand) still debated in sports bars in Latin America, landed what became known as “the Hand of God.” It would not be the last time Maradona’s name would be associated with the divine.

The central figure in “Diego Maradona” is still alive by the film’s end. More than that, he has died several times over and come back to tell the tale.

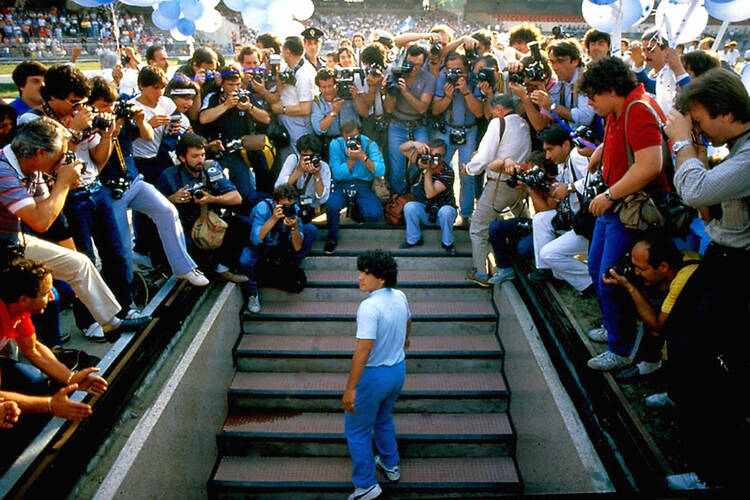

Although everyone remembers Maradona’s spectacular run in the 1986 World Cup, the director Asif Kapadia’s first memory of him goes back to the 1982 Cup in Spain, where the enfant terrible of soccer underwhelmed audiences with a poor showing marked by defensiveness, violence and his eventual expulsion from a match against Brazil, “when he kicked someone in the groin,” recalls the filmmaker during our telephone conversation.

Although even back then he had been touted as the world’s greatest soccer player, Maradona would patiently wait four years to deliver what Mr. Kapadia calls “the best solo perform performance in a World Cup.” Argentina emerged as world champion in 1986, and Maradona’s stratospheric rise and his eventual fall from the top made him the perfect choice for Mr. Kapadia to follow his Oscar-winning documentary “Amy” and the endlessly moving “Senna.”

Except unlike the tragic figures of his first two documentaries, who met their demise much too early, the central figure in “Diego Maradona” is still alive by the film’s end. More than that, Maradona has died several times over and come back to tell the tale.

Constantly reinventing his career, surviving heart attacks and drug addiction, Maradona occupies a special niche for many fans—that of a living god.

Constantly reinventing his career, surviving heart attacks, drug addiction and dealings with the Camorra, Maradona occupies a special niche for many fans—that of a living god. In 1998, three of his fans founded the Maradonian Church in the city of Rosario, Argentina, a religion embedded in the mystery of the man who was born in the slums, became a prophet in faraway lands and was eventually betrayed by those who should have protected him. Believers cannot get enough of his parallels to Jesus Christ. They gather every week all over the world where they share testimonials of Maradona’s effect in their lives, are baptized in a ritual that involves them recreating “the Hand of God” goal and celebrate their own version of Christmas on October 30 (Maradona’s birthday). These days, members can join the church via Twitter (@Igmaradoniana).

Maradona himself is reluctant to accept these comparisons. In archival footage from Mr. Kapadia’s documentary he contradicts an Italian TV presenter who declares “Neapolitans have Maradona inside them more than they do God,” and when a fisherman establishes that “if you speak badly of Maradona you are criticizing God,” one can almost hear the thunder crackling in the sky at the blasphemy.

Half a million devotees of the Maradonian Church have repurposed the Lord’s Prayer to pay tribute to their modern Messiah.

When Maradona became the star of the lesser-known Napoli team, after a brief unsuccessful stint with the world-renowned Barcelona team, he lifted the poverty-stricken Italian town to the attention of the world, with locals suggesting he was the second coming of Saint Gennaro, the Christian martyr whose magical blood is the cause for celebration and awe three times every year at the Naples Cathedral.

It is no coincidence that half a million devotees of the Maradonian Church have repurposed the Lord’s Prayer to pay tribute to their modern Messiah:

Our Diego, who art in Earth

Hallowed be thy left leg

Thy magic come,

Thy goals are remembered,

On Earth, as they are in Heaven.

Despite its apparent irreverence, the Maradonian Church mimics Catholic structures and echoes the Ignatian intention of finding God in all things, even when it is a 5-foot-8 Argentinian soccer player who, against all odds (including colorism, as he was the object of criticism for his darker skin color), became a figure of hope. “He has the most unusual body shape, but he has a really low center of gravity and moves like a dancer,” explains Mr. Kapadia.

For the Italian filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino, who features a thinly disguised version of Maradona in his film “Youth,” soccer performed a miracle. When he was 16, Sorrentino skipped a family trip to see Maradona play with Napoli. That weekend, his parents were killed in an accident. “Maradona saved my life involuntarily,” he said in an interview with Variety.

“Wherever he goes, he brings hope, he does miracles, becomes a disaster, dies, and leaves everyone thinking it’s over, only to appear in a new place and repeat the cycle,” says Mr. Kapadia.

Although the filmmaker is best known for his documentaries, he confesses that even as he tells other people’s stories through nonfiction, there is something quite personal in each of them. With “Diego Maradona,” he was finally ready to look back at his childhood hero without the veil of adolescent fandom and devotion. “I’m older and can now look at the complications of the freedom you have, the complexity of life, surviving and family and children and relationships,” says the director.

In his latter days, Maradona has rediscovered the simple joys of spending time with a football. “The most beautiful thing in life is him messing around with his ball,” Mr. Kapadia says. “He’s never happier, his tongue sticks out the side of his mouth, he’s got his shoelaces undone, and there’s nothing better than chasing a ball around.”

Before we hang up, Mr. Kapadia says right after our interview he will go out in the rain and play some football. “That’s the one time in the week when I can forget all the work and the stress. Sometimes you just want to go kick a ball and forget everything.”

His words took me back to that fateful match on June 1986, when Maradona scored what has been deemed The Goal of the Century, a feat of ballet, animalistic hunger and divine inspiration that led Uruguayan commentator Victor Hugo Morales to break down on live TV, crying “Thank you, God, for football, for Maradona, for these tears,” perhaps delivering the first prayer in a church that was yet to be formed.

“Diego Maradona” is now streaming on all HBO platforms.