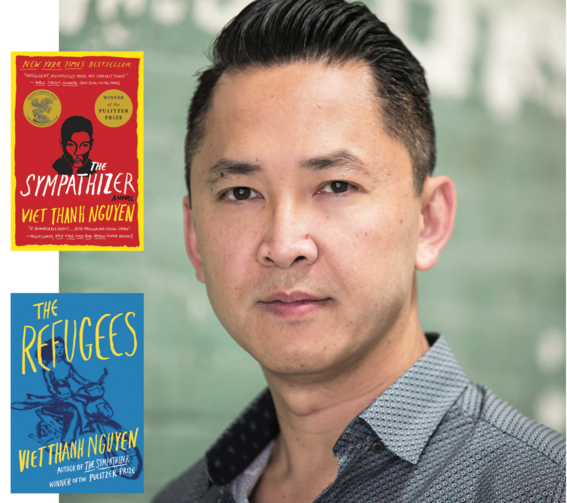

When Viet Thanh Nguyen’s bold and mesmerizing debut novel The Sympathizer received the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in fiction, it was an honor that took him by surprise. Having fled Vietnam in 1975 with his family at a young age, Nguyen was the first Vietnamese-American writer to win the Pulitzer. The Sympathizer, with intense and ironic prose, wrestles with issues of identity and loyalty through theconfession of a communist double agent during the Vietnam War.

This month Grove Atlantic releases Nguyen’s The Refugees, a collection of eight short stories written over a span of 17 years. Nguyen’s stories deal with ghosts and patriotism, mental illness and infidelity, and gender roles and homosexuality, among other topics that highlight the tensions and complexities involved in the refugees’ search for identity and belonging. The stories humanize Vietnamese-Americans who do not always fit the inflexible “model minority” stereotype. They take a segment of the American population not always on the social radar and bring it into sharp relief.

I spoke with Nguyen over Skype while he was on Christmas break with family in San Jose. This interview has been edited and condensed.

In The Refugees, you make it difficult for readers to point out the “real enemy.”Your stories don’t allow for easy answers.

That reflects just how I experienced life in the Vietnamese-American community. There were just so many situations that people found themselves in that really had no easy answers. People were suffering from various kinds of trauma. They were human beings who were trying to survive in the United States, but also deal with all kinds of complications with their families, and their children, and their partners. Some people made good choices, some people made bad choices, and some people made choices whose consequences depended on how you were looking at them.

You have a gift for humanizing characters of opposing sides.

Our job is to humanize the communities that we come from to people who don’t know anything about these communities. That’s important to do, but it’s also very constricting because writers who are not a part of the minority don’t feel that obligation. They don’t feel they have to humanize anybody because it’s already understood that they’re human. If they’re a part of the majority and if their readership is a part of the majority, you don’t need to explain the humanity of your own community to someone of your own community.

Each age group of Vietnamese-Americans will receive and process your stories from The Refugees differently—and certainly, differently from non-Vietnamese Americans as well. Who were you imagining reading these stories when you were composing them?

I had a couple of different audiences in mind. I had readers that I thought I wanted to reach out to. And those would be other Americans, but certainly also Vietnamese-Americans as well. But then, also lurking in my mind were the readers who could really make a difference to a writer, and those readers were editors, agents and publishers. And that was, I think, very debilitating for me. I was worried about my career, and recognition, and all those kinds of worldly things…. For The Sympathizer, I had a very different audience in mind, and the audience was me.

The topic of faith comes up often in your writings; you’ve mentioned Catholicism a lot. Did you grow up Catholic? Did you have statues and rosaries all over the place, like my family does?

If I turn the camera around you can see that I’m facing three Catholic pictures on the wall that my parents have hung up. You know, Jesus, Mary and Joseph; Saint Theresa; and Pope John Paul II. These are the kind of things that I grew up with on my bedroom wall. And my parents were extremely devout Catholics. They were born in the north before 1954, and then they were part of that wave of Catholics that came south. I was raised as a Catholic, I went to Catholic school, and then Jesuit prep school, and went to church every week. So I grew up saturated in Catholic mythology, if that’s what you want to call it, but Catholic culture as well. Ironically, despite all the money and effort that my parents spent on turning me into a Catholic, I’m not a very good Catholic.

You went to Bellarmine Jesuit Prep in San Jose. How was that experience, being a first-generation Vietnamese-American in a mostly white, affluent school?

It was a mixed experience where, on the one hand, it was a great education. I read all kinds of things that I think most people my age weren’t reading. So I was reading Faulkner, and Joyce, and Karl Marx. And I was also being inculcated with Jesuit and Catholic values of service to others, which was a major part of the curriculum at Bellarmine, and that has always stayed with me…. But on the other hand, it was primarily an all-white school, and mostly white curriculum, and that had a negative impact on me and other students of color at the time. We didn’t have a political consciousness, so we couldn’t articulate who we were. We knew that we were different.

The topic of identity comes up a lot in The Refugees.How do questions of belonging and identity, race and racism differ for Asian-American citizens now, in comparison to your generation?

I’ve seen younger Asian-Americans who’ve grown up in California, in the urban neighborhoods, take being Asian-American for granted. They’ve always been surrounded by Asian-Americans, and so for them there’s less of an impulse to make identity into an important issue because it’s simply a fact of their life. They haven’t experienced discrimination, they haven’t even experienced not being a part of the majority. That’s a very different experience than what I had. I think that’s why when I went to college, taking Asian-American studies classes and ethnic studies classes was very important to me.

In almost all your stories in The Refugees, amid the tensions and all the struggles, there always seems to be a strong woman in the background. Was that intentional?

Yeah, definitely. And it’s very different from The Sympathizer. The Sympathizer is told from a very heterosexual, masculine point of view, and there’s a lot of sexism as a result of that. But in The Refugees, I really set out to try to capture a diversity of experiences, which meant I was literally mapping out stories thinking, “Okay, do I have women? Do I have young girls? Do I have older men? Do I have civilians? Do I have veterans?” I really wanted to get a broad demographic of the Vietnamese-American community.

You have stories about women’s roles, sexuality and sexual orientation, and fidelity. What’s the one thread that runs through all of these stories?

It was obvious to me that people’s lives, even as they were defined and constricted by ethnicity and race, they saw themselves as Vietnamese people in a white country. Within that, they defined themselves through sexuality and gender, their place as men and women, or as boys and girls learning to become men and women. They were very conscious of the choices that they were making according to their gender and their choices in sexuality as well. That was very much part of the drama of being Vietnamese in this country. I would grow up hearing stories of domestic violence and of parental abuse of children, and men going back to Vietnam and never returning because obviously, they found another partner. And people losing their identities because they no longer could be the patriarchs of the family.

I feel especially grateful to you.Being a second-generation Vietnamese, reading these stories, they certainly resonated with my experience, and I’m sure with the generation before me.

I do hope that Vietnamese-Americans, especially, find something relevant in these stories. I don’t know how it was for you when you were growing up here, but when I was growing up, you didn’t have these kinds of stories. And I also hope that the book is going to be read in Vietnam. It’s supposed to be translated, and I think there’s a lot miscomprehension in Vietnam about the lives of the Vietnamese diaspora. So I hope the book helps to explain some of those experiences for the people in Vietnam.