UPDATE: A federal judge on Jan. 15 issued a preliminary injunction, suspending President Donald Trump’s executive order. U.S. District Judge Peter Messitte in Maryland said in his ruling that the president's order “flies in the face of clear Congressional intent" of the 1980 Refugee Act by allowing state and local governments to block the resettlement of refugees in their jurisdictions.

New bureaucratic obstacles created by a Trump administration executive order have forced refugee advocates to scramble in recent weeks. Advocates say refugee programs have for years placed people fleeing conflict or humanitarian crises in communities across the country without controversy.

But the executive order, issued in September, requires for the first time that resettlement agencies get written consent from state and local officials in any jurisdiction where they hope to place refugees after June 2020. That new federal mandate created a giant headache for Sandy Buck, the regional director of Catholic Charities for the Diocese of Charlotte in North Carolina, one no doubt shared by other Catholic Charities directors around the nation.

“This has really been a bear for me because of the time that it’s taken up,” she said. “It’s created chaos, which I think it was designed to do.”

According to the order, the administration seeks to take into account the preferences of state governments “and to provide a pathway for refugees to become self-sufficient.”

“These policies support each other,” the order states. “Close cooperation with State and local governments ensures that refugees are resettled in communities that are eager and equipped to support their successful integration into American society and the labor force.”

The executive order, issued in September, requires for the first time that resettlement agencies get written consent from state and local officials in any jurisdiction where they hope to place refugees after June 2020.

As advocates and service agencies struggle to follow the new mandates, the order itself is being challenged in court. In acomplaint filed in November, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Church World Service and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service argue that the president’s executive order violates federal law and inhibits their ability to practice their faith. The organizations seek an injunction to temporarily stop the jurisdictional consent requirement. A ruling is expected this week.

When Mr. Trump issued his executive order, “it was very unclear what we were supposed to do,” Ms. Buck said. A storm of conference calls and discussions with Catholic Charities affiliates and with representatives of the other eight national organizations engaged in refugee resettlement followed. She added that people in local government “had no idea what was happening and didn’t understand refugee resettlement.”

“So we had to do a lot of educating and trying to help people understand what we were talking about when we say ‘refugee resettlement,’” she said. “Unfortunately, the word refugee has a very negative connotation because of things in the news.”

She hears local politicians expressing a “fear of the unknown...unfortunately, this is becoming a political issue,” she said. “It should be a humanitarian issue, but it’s becoming a political issue.”

In recent weeks Ms. Buck has offered presentations on the reality of Catholic Charities’ program to county government officials throughout the region served by her office. Some quickly consented to refugee resettlement, but some tabled the discussion without a decision. “I got a lot of pushback,” Ms. Buck said.

Some county officials, she said, equated the handful of refugees that Catholic Charities of Charlotte was assisting with images of desperate people pressing up against the borders of Europe after fleeing conflict in the Middle East. Ms. Buck explained to officials that most of the clients accepted by her office represented family reunification cases. Most refugees coming to the Charlotte area were escaping conflict in Ukraine, Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to Ms. Buck.

What she hears back are local politicians expressing a “fear of the unknown,” she said, advising her that “putting families together, we’re okay with that,” but expressing alarm at new arrivals from “third world countries” and specifically Syria.

“Unfortunately, this is becoming a political issue,” she said. “It should be a humanitarian issue, but it’s becoming a political issue, and I find that when I’m talking to commissioners who are Republicans, I have a little bit harder time getting them to understand and provide that consent.”

Greg Abbott, the Republican governor of Texas, announced that his state would become the first to refuse the resettlement of new refugees. The governor’s decision was quickly criticized by the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops.

Despite the new administrative and political pain, Bill Canny, executive director of the U.S. bishops’ Office of Migration and Refugee Services, had some good news to report. “We have 41 ‘yays’ so far,” he said, explaining that governors across the country, both Democratic and Republican, had agreed to keep their states open to refugee placements.

But just a day after Mr. Canny’s optimistic assessment, Greg Abbott, the Republican governor of Texas, announced that his state would become the first to refuse the resettlement of new refugees. The governor’s decision was quickly criticized by the Texas Catholic Conference of Bishops, which called the move “discouraging and disheartening” and “simply misguided.”

“It denies people who are fleeing persecution, including religious persecution, from being able to bring their gifts and talents to our state and contribute to the general common good of all Texans,” the Texas bishops said in a statement released on Jan. 10. “The refugees who have already resettled in Texas have made our communities even more vibrant,” they said. “As Catholics, an essential aspect of our faith is to welcome the stranger and care for the alien. We use this occasion to commit ourselves even more ardently to work with all people of good will, including our federal, state and local governments, to help refugees integrate and become productive members of our communities.”

In a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, released to the press on Jan. 10, Gov. Abbott, a Catholic, wrote that Texas “has been left by Congress to deal with disproportionate migration issues resulting from a broken federal immigration system.” He said that Texas has done “more than its share.”

“At this time, the state and nonprofit organizations have a responsibility to dedicate available resources to those who are already here, including refugees, migrants, and the homeless—indeed, all Texans,” he argued.

Ms. Bucks believes the consent hurdle thrown up by the Trump administration reflects an undeclared effort to sharply reduce refugee placements in the United States.

Since 2002, Texas has resettled an estimated 88,300 refugees, second only to California, according to the Pew Research Center.

Many refugees who hoped to reach Texas this year were likely planning to join family already there. But now “there are some refugee families who have waited years in desperation to reunite with their family who will no longer be able to do so in the state of Texas,” Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, president and C.E.O. of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, told The Associated Press.

A number of Republican governors across the South and in Wyoming have yet to make a decision on resettlement, but fellow Republicans who have consented to refugee placements within their state borders have faced some tough intraparty criticism for those decisions.

Ms. Buck believes the consent hurdle thrown up by the Trump administration reflects an undeclared effort to sharply reduce refugee placements in the United States, even as the global number of internally displaced and refugees, at 71 million, represents the gravest crisis of uprooted people since the end of World War II.

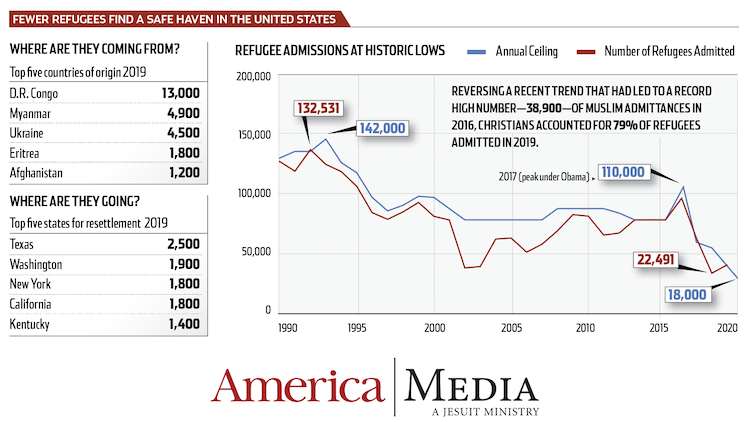

Each year since his election in 2016 Mr. Trump has lowered the presidential determination for refugee admittance, a kind of refugee quota (actual resettlement numbers are usually lower). Refugee ceilings of 70,000 to more than 90,000 had been consistent since 1987, but the presidential determination last year was just 30,000, and the president agreed to allow no more than 18,000 refugees into the United States for 2020—a historic low (see infographic above).

“This has really been a bear for me because of the time that it’s taken up,” she said. “It’s created chaos, which I think it was designed to do.”

“At Catholic Charities in Charlotte, we used to resettle 350 to 400 refugees a year,” Ms. Buck said. Last year? “About 157.”

“We were happy to get 18,000 [for 2020],” said Ms. Buck, “but my sense is that [the Trump administration] would like it to be zero.”

And as the numbers decline, the viability of refugee resettlement offices diminishes with them.

“Our leadership is entirely dedicated to keeping the program open,” said Ms. Buck. During other periods when arrivals were low, she said, Charlotte Catholic Charities kept the office afloat with private donations. “But if [the presidential determination] goes to zero next year, I would imagine that the program would have to go away. We can’t sustain it without new arrivals.”

Mr. Canny reports that as many as 25 Catholic Charities refugee offices around the country have already closed. “The agencies are being reimbursed on a per refugee arrival basis,” he said, “so it’s just extremely difficult for them to maintain staff to support and assist these refugee families with housing, health care, education for their kids [and other services like] English as a second language [programs].”

He added that the Trump administration plans to shut out a so-far-undisclosed number of the nine social service agencies that manage resettlement agencies next year. “We all have been duly warned, if you will, that given the lower number of refugees coming in, they may eliminate the entire infrastructure of some of the nine agencies.”

That will likely sound just fine to critics of refugee resettlement programs, who perceive refugees as an unwelcome social and economic burden and who frequently accuse church-based providers like Catholic Charities of cashing in on federal largess through their assistance programs for refugees. The idea provokes a chuckle from Mr. Canny.

“Yeah, that’s entirely incorrect,” he said. While he hopes that support staff are paid a fair wage, he explained that federal contracts are based on well-defined formulas and audited spending expectations per individual refugee client. A percentage is retained by affiliates for their overhead and staffing costs.

“Those affiliates have been bleeding over the last few years,” he said. “What we do know is that for the Catholic agencies, the money that is given by the federal government is supplemented by donations in kind and in cash and many, many volunteer hours. The [local] Catholic church and their community participate heavily in this program.”

“Our faith calls us to welcome the stranger, but people still have to feed their family,” Ms. Buck said. “They can’t be expected to do it for free.”

Federal dollars keep resettlement offices open, but “it’s not a moneymaker” for Catholic Charities, she added. “We’re just trying to keep the lights on and pay our people a fair wage to do some sometimes very difficult work.

“We do depend on people of good will to help with the programs,” she said, noting donations of furniture that help fill empty apartments for new arrivals, as well as volunteers who develop “mentor-type relationships with people coming in to help them acclimate, learn the language, learn the culture.”

“It is a public-private partnership,” Mr. Canny said of the federal process for supporting incoming refugees, “and it’s a good partnership that’s been built historically on mutual trust, understanding and information- and cost-sharing. Under this administration, that partnership has been disrupted.”

Mr. Canny hopes before too long to see a changing attitude about refugees in contemporary U.S. political culture, restoring a perception of these new arrivals as vibrant and welcome contributors to U.S. life. “These refugees come over, they’re hungry to work.... These refugees are actually an asset to us both economically and, frankly, culturally.”

He added, “I would say, finally, they give us an opportunity to exercise our compassion, and we need opportunities to be compassionate.

“They build our own humanity,” Mr. Canny said.