Police and protesters fought running battles in the narrow streets of Tegucigalpa today. But in the end, Honduran security forces were able to hold back demonstrators who sought to press closer to the National Stadium where Juan Orlando Hernández was being sworn in for his second term as president.

Details of the inauguration were kept from the public and though more than 20 nations—including the United States—have recognized the new president, none of the usual foreign heads of state were present for the ceremony. An election in November marred by irregularities, allegations of fraud and conveniently timed computer breakdowns at the Supreme Electoral Tribunal may have been the reason for the low-profile event.

In northern Honduras, sporadic protests provoked an occasional overreaction by police. Police this morning fired tear gas into a hamlet near San Pedro Sula, the nation’s second largest city, apparently as recompense for a street barricade that had been erected by the community’s young people, but so far today there has been little of the widespread disorder present in the nation’s capital. The region around San Pedro Sula is rich with supporters of the losing candidate, sportscaster turned opposition leader Salvador Nasralla. In the weeks after the election, clashes with police and military resulted in the deaths of more than 20 demonstrators in this region.

Today the head of Congress put the blue-and-white sash of office on Mr. Hernández in the morning ceremony in Tegucigalpa, and the president promised in his inaugural address “to begin a process of reconciliation to unite the Honduran family.”

But Mr. Nasralla did not sound ready for that reconciliation just yet. Noting the disorder and security presence in Tegucigalpa, “this is how the dictator oppresses his people,” he said. Mr. Nasralla told the Associated Press that he continues to believe the election was stolen and that he was the true winner of the vote.

“We remain in the struggle to rescue the country from dictatorship and without recognizing Hernandez as president,” he added.

Driving through the barrios of San Pedro Sula, the presence of national police and military as well as private security is readily evident. Security forces took up positions throughout the city and at strategic points along national highways. Sites where previous protests ended in fierce clashes, a Pizza Hut torched by election protesters in one community and a much-loathed toll plaza scorched in another, were manned by squads of heavily armed and often masked military and national police. Their presence seemed to have the desired effect; few protesters had appeared on the streets as the swearing-in ceremony in Tegucigalpa grew closer this morning.

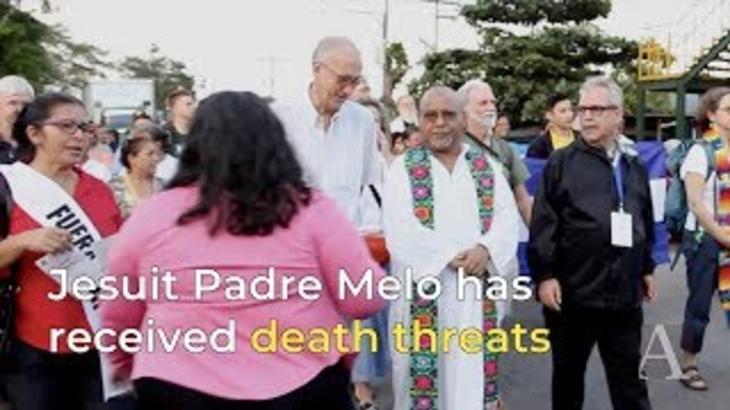

Reporters from Jesuit-supported Radio Progreso believed that many who may have previously been considering joining a demonstration against the Hernández government have been sufficiently intimidated into inaction this week. Several recent acts of violence by police and state security have frightened many.

In Atlántida, an adjoining department to San Pedro Sula’s department of Yolo, two men involved in activism against a hydroelectric dam project were killed this week. Ramón Fiallos, 65, was shot down by police in the streets of his community in the late evening on Jan. 22. A few hours later, at 4 a.m. on Jan. 23, a young father, Geovanny Díaz, was pulled from his home before his screaming children, dragged into an alley and riddled with bullets. According to witnesses, the assassins were men in police uniforms.

And on Jan. 26, the home of a local opposition politician was raided by police; two family members were threatened at gunpoint and another allegedly assaulted. Official impunity and the use of lethal force by the national police are described by Human Rights Watch as chronic problems in Honduras.

Despite those acts of apparent state-sponsored violence, some still felt compelled to make their voices heard today. On the streets in Choloma and San Pedro Sula this morning, small groups of protesters assembled and were alternately cheered or jeered by passersby.

The usual chants of “Fuera JOH!”—“Out with JOH!” (using the abbreviation of the president’s name)—were accompanied by new slogans: “Este delincuente, no es mi presidente!”—“The criminal is not my president”—and “No to dictatorship; yes to democracy!”

One man maintained a lonely protest alongside the highway leading to Choloma, a blood red “Fuera JOH!” sign his only companion before another demonstrator pulled over to join him later in the day. The newcomer’s sign deplored the “death of democracy” in Honduras.

The two young men stood between squads of police who were guarding the burned-out toll booth. Both men insisted they were not afraid to protest quite literally among the police.

“We have to defeat fear or we can never overcome this government.”

“Fear is the worst weakness of humankind,” the protester holding the “Fuera JOH!” sign said. “We have to defeat fear or we can never overcome this government.” Any confidence in the impartiality of the electoral process has been taken from the Hondurans, he said. Now “to protest is the only right we have left.”

Noting my presence, a reporter from the United States, he added, “I’m glad you are here; you have to explain what is happening in Honduras.”

As he spoke, a car-load of young men approached, shouting their support. He watched them pass by. “It would be better if people stopped and joined us,” he said.

He gestured to the streets filled with pedestrians, delivery and industrial truck drivers and motorists going about their business as if it were a normal Saturday morning. “You’ll see all this and you will think everything is fine in my country,” he said. “But that is not the truth; the truth is we have a murderous government in Honduras now.”

“The truth is we have a murderous government in Honduras now.”

Over the past hour several police cars had slowed and taken his picture. He does not know if those were just minor acts of intimidation or if they might truly mean security forces will one day come for him as they had allegedly done in Atlántida. “But I want you to know, if something happens to me, it will be the government of Juan Hernández that is responsible,” he said.

Then he defiantly offered his name and age for me to add to this report. For the first time in my career, I am choosing not to include that information here.

With content from the Associated Press.

Curiously, not a peep out of the esteemed editors of America on the assassination of protesters. Perhaps a perusal of the New York Times is in order.